The hordes of tourists who clog the streets of Kyoto don’t know that within a stone’s throw from Japan’s former capital, Shiga Prefecture has some of Japan’s best and most underrated shrines and temples. Among these, Ishiyama-dera stands out for a number of reasons.

Its most distinctive feature is that, as its name makes it clear (ishi-yama-dera mean “stone-mountain-temple”), the religious complex was built on a cliff overlooking the Seta River. The cliff is made of Wollastonite, a rock formed when granite magma comes into contact with limestone. On the temple grounds, there are spectacular rock formations that were designated as a natural monument.

Over 10 meters tall, they showcase swirling patterns created by overlapping layers of magma. Frozen in time by volcanic activity and fractured into jagged edges through geologic processes, they stand as a dynamic testament to nature's artistry and power.

A pagoda standing in the background seems to float on waves of molten rock. It expresses the Buddhist concept of rising spiritual levels. As Alex Kerr writes in Hidden Japan,

We pass through the storms and turmoil of a messy human life to reach in the end a pure world about above it all. The peaceful pagoda crowning the turbulent stone is a summing up of Buddhist philosophy.

The pagoda takes a particular shape known as a tahoto, a structure unique to Shingong Buddhism. It dates back to Kukai, the charismatic monk who traveled to China in the 9th century and returned to Japan bringing advanced knowledge of esoteric teachings.

Kerr explains that a tahoto consists of a square lower section surmounted by a round plaster middle part, and above that a four-sided pyramidal roof. “Each tahoto symbolizes sacred Mount Sumeru, center of the universe.” In religious architecture there has long been a contrast between karayo (Chinese style), masculine and muscular, and wayo (Japanese style), feminine and elegant. This pagoda is wayo in its purest form.

Ishiyama-dera was founded in 747, during the Nara period, by a monk named Roben, the same who founded Nara’s Todaiji. According to legend, when the Great Buddha of Nara was made, there was not enough gold to decorate its giant body, so Emperor Shomu asked Roben for spiritual help. Soon after, a large amount of gold was discovered, and Ishiyama-dera was built on the site where Roben had come to pray.

Ishiyamadera is also widely considered one of the best spots in Japan to enjoy autumn’s beautiful red, orange and yellow leaves. But even if you, like me, can’t visit the place in the fall, don’t worry because the so-called Temple of Flowers has a variety of species that bloom throughout the year, including sakura, plum and camellia.

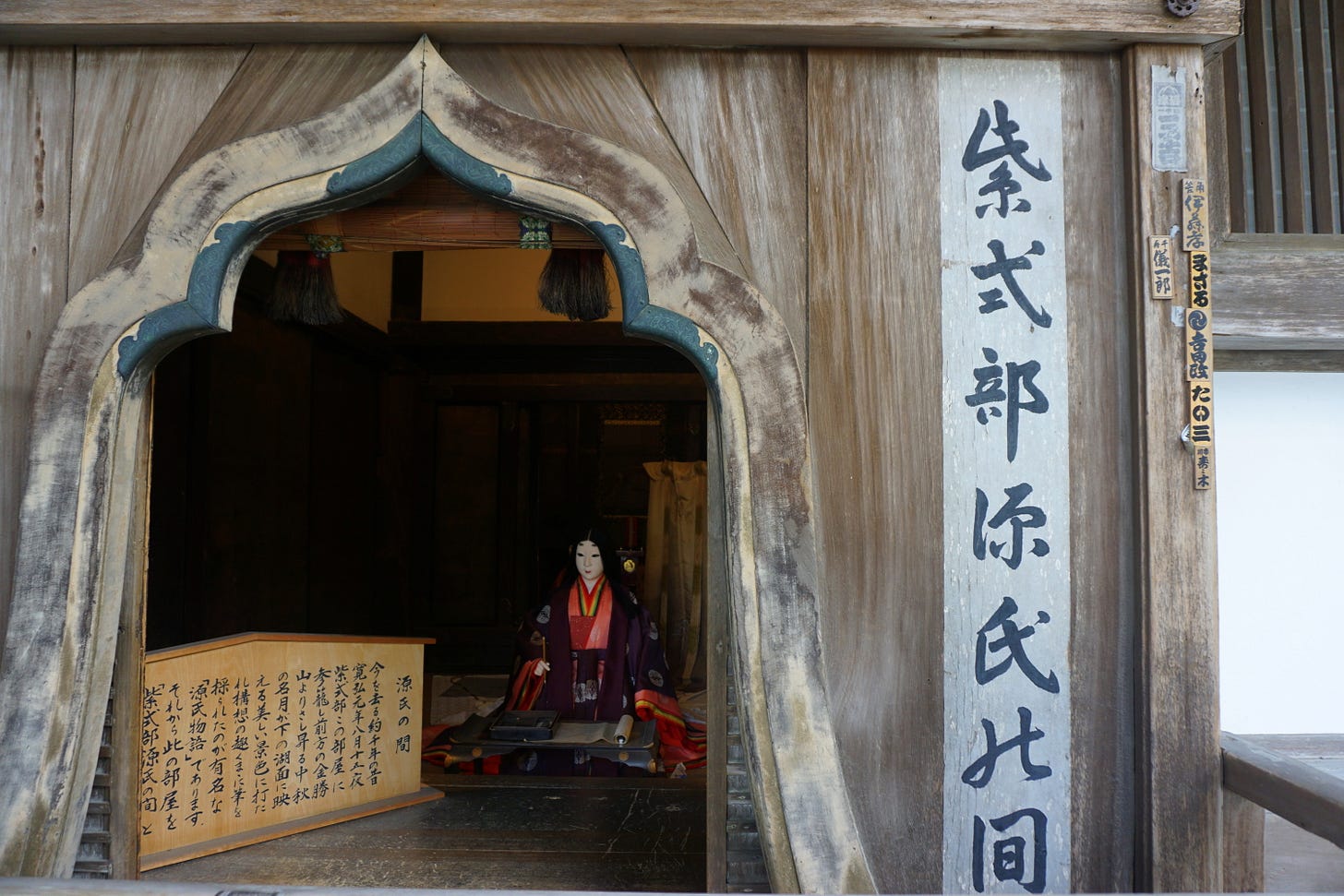

Nature aside, the temple is known among literary buffs for attracting many authors. Murasaki Shikibu, for instance, stayed at Ishiyama-dera for seven days, and there is a legend that she was inspired to write the Tale of Genji while watching the moon reflected on Lake Biwa. The temple also appears in much Heian period diary literature, from Kagerou Nikki to Sarashina Nikki and Izumi Shikibu Nikki, which, incidentally, were all written by women. Many other literary figures visited in later times and left references to Ishiyama-dera in their works, from haiku great Matsuo Basho to Shimazaki Toson, Yosano Akiko, and even Mishima Yukio.

When I visited Ishiyama-dera, knowing fairly little about the place, I was not prepared for what was awaiting me inside. The East Gate – its main entrance – is guarded by two stately Nio statues. Built with a donation from Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first ruling shogun in Japanese history, it was later extensively repaired with a donation from Yodo-dono, a concubine of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Yet, compared to other famous temples, it is a relatively unassuming gate that offers no indication of the vast grounds beyond it.

However, once inside, the temple features plenty of stairways and winding paths leading to smaller halls, shrines, and vantage spots overlooking the city and river below. It can easily take at least a couple of hours to explore the place properly.

The heart of Ishiyama-dera is the Hondo (Main Hall), designated a National Treasure. This impressive wooden structure, rebuilt in 1096, is the oldest building in Shiga Prefecture. Like Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto, it is supported by wooden pillars assembled like scaffolding. Inside the Hondo, you will be greeted by many Buddhist statues, including Kobo Daishi, the founder of Shingon Buddhism, Bishamonten, and Nitenzo.

If you keep climbing, you will see the magnificent Kodo (Light Hall). Going down to the left from there, you will eventually arrive at the much-talked-about statue of Murasaki Shikibu.

Ishiyama-dera is the kind of place that if it were located in a major city, would be besieged by tourists, day in and day out. Yet, this temple is mostly visited by locals and is so big that it often feels almost empty.

“To tell you all the truth, I want to avoid overtourism, if possible,” says Washio Ryuge, the temple’s head priest I interviewed on that day. “This said, temples are places that attract all kinds of people, and I would like them to come any time they want, whenever they want. I also hope that their visit will become a precious memory. That’s why I think it would be good if there weren't too many people.”

As Ishiyama-dera’s head priest, Washio-san is, in a sense, the temple’s most distinctive “feature” since in Buddhism, women are still a small minority. “I was born and raised in Ishiyama-dera,” she says, “and I wanted to become a monk from a young age. Partly it is because I admired my grandfather, who was the head priest at the time, but I was especially in love with the whole daily routine of temple life. Every morning, I prayed with my mother, putting my hands together and sharing with the Buddha any occurrences, or I would sit in front of the temple and think about anything that was bothering me. I've done this every day since I was little, so I've always wanted to live in this kind of world.”

After a long training, Washio-san took the last decisive step in that direction four years ago when her father died in December 2021. “At that time, my mother and I were left behind,” she says, “and when I was asked again what I would do, I had no doubts that I wanted to replace him as the head priest. Looking back now, it seems a little surprising that no one opposed my decision, but from a young age, both my father and grandmother had encouraged me to do so, and no one ever told me I couldn’t do it because I was a girl.

“I never really thought much about gender issues, but since I was appointed to the position of head priest, I have started to be a little more conscious of it. Now I look around me and see that most monks are male.”

Buddhism is an eminently male world. According to Washio-san, each Buddhist sect is different, with Jodo Shinshu being the one with the strongest female presence (about 15%) while in her own sect, Shingon, women priests are about 10%. Also, having the qualifications to be a monk and actually becoming a head priest are two different things.

While Washio-san has never been discriminated against for being a woman, she feels that there is still room for improvement. “I think I’ve been relatively fortunate in this respect,” she says. “However, our bodies are different and there are times when people don't realize that there are things that only women can understand. When men and women work together, certain problems arise that must be dealt with. For example, before a ceremony, everyone is supposed to change in the same room, but for me, being the only woman, it feels wrong. Still, I don’t want to be a nuisance, so I end up changing in the restroom. I think that's probably the hardest part of being a female priest.

“There is no system or opportunity for everyone to recognize that we, female monks, are struggling with such situations. I feel that women are sometimes overlooked because there are so few of us. However, there is a growing awareness that men and women should work together. Partly it’s because there are more women involved. Like me, there is a growing number of daughters of temple priests who want to become Buddhist monks, so I think the system will probably change for the better in the future.”

Washio-san’s job as the head of Ishiyamadera can be broadly divided into two parts: spreading Buddhism and protecting the temple. “In the morning, I always pray at the Main Hall,” she says. “After that, it varies depending on the day and the memorial services I have to officiate. I also give speeches and lectures to a variety of groups and institutions including schools and kindergartens.

“Then, I'm always thinking about how to maintain the temple as a place where everyone can come and pray. For example, if I realize that one of the paths is difficult to climb, I need to fix that. Then, there are bigger issues to consider. The Main Hall is the oldest building in Shiga Prefecture, and if the floor is damaged, it needs to be repaired. However, since it's a cultural property and a National Treasure, we can't do it by ourselves; we need to consult the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the local authorities to make a plan and see how long it will take to complete the job.

“The temple plays an important role in this area, and we are committed to supporting the local community in any way we can. Also, as it is a tourist attraction, we always collaborate with other people and institutions. For example, the story of Murasaki Shikibu became a popular taiga drama (historical TV drama) last year that was shown on NHK, Japan’s public broadcaster. So the Taiga Drama Museum was installed in the temple grounds and we had to think of various ways to make it easier for people to visit the temple. Being the head priest of such a big temple is quite a responsibility, but in the end, the thing I enjoy the most is praying. Every time I go to the Main Hall, it's either very cold or very hot, but I find that the time I spend praying is the best.”

Being the head priest of a big temple, Washio-san is constantly reminded of its historical legacy and the traditions she is supposed to protect. On the other hand, though, she is trying to introduce new things to adapt Ishiyama-dera to the changing times.

“Since this temple has been around for 1270 years, I think a lot about what to keep and what to change,” she says. “In my opinion, the best thing is to strike the right balance between the two in order to best convey our ideas and values. Of course, the current events and ceremonies are traditions that have been passed down for centuries and need to be kept in place, but I would like to expand on them, so there will probably be more events in the future. I don't think that people know much about what we do. Particularly in Shingon Buddhism, there is a tendency for monks to work alone. Sitting alone and praying to the Buddha is an important part of our work, of course, but at the same time, we need to reach out to the people who come to pray and get them more involved. I want to do things that will make them think of the temple as a place where they belong.”

Deeply informative article, Gianni, as always. Nice to see a female perspective. Thanks for including that. The temples and environment look serene and beautiful.

The place has a natural rugged beauty, the buildings are magnificent, and tradition and modernity meet harmoniously under Washio-san's direction. You did them proud with this article, Gianni. I also appreciate the mention of Dame Murasaki, I find her monument remarkable: see how the folds in her coat mirror those of her paper sheets, with all the lines so fluid and elegant, like in a master calligrapher's writing.