Dear readers, sorry to be late. I just spent three hectic weeks working on a special issue on Okinawa for Zoom Japan magazine and had to put aside this newsletter for a while. I hope you missed me!

While holing up at home doing online interviews and writing furiously, I began to miss my walks around Tokyo and was reminded why I love this crazy architectural monster of a city. So this is the first part of a piece I wrote two years ago to celebrate Zoom Japan’s tenth anniversary and 100th issue.

As usual, please share this story widely and help spread the word about Tokyo Calling.

In 1998, for the first time in history, the number of people living in cities around the world surpassed rural population. Japan is by no means extraneous to this phenomenon. It is clearly visible everywhere, and especially along the old Tokaido road where – from Tokyo to Nagoya to Kobe – one conglomeration fades into the next one.

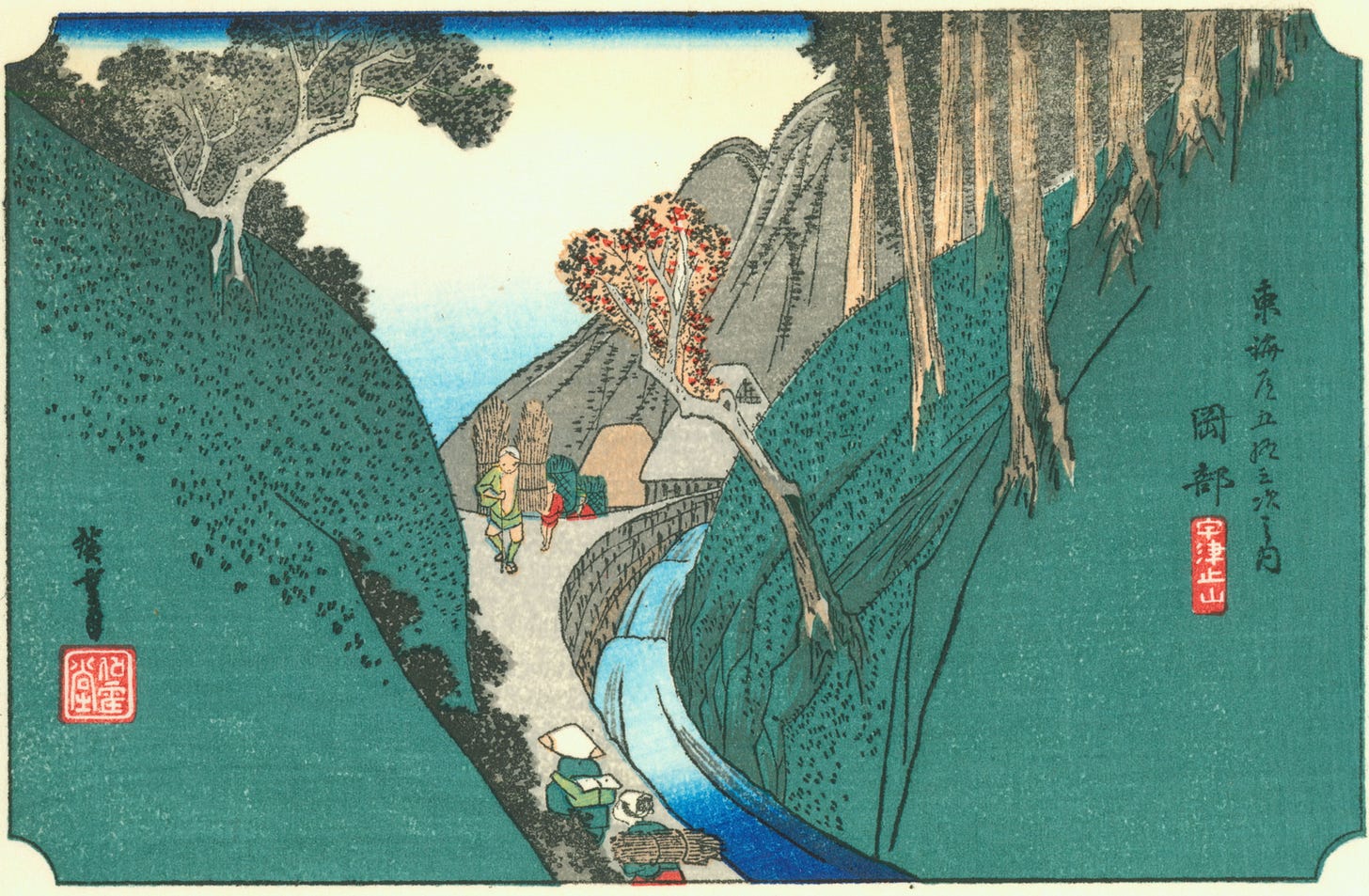

Il the 19th century, the Tokaido looked like this (woodcut print by Hiroshige)

The biggest one, of course, is Tokyo. With 38 million inhabitants, the so-called Greater Tokyo is the world’s most populous metropolitan region. It also ranks as the largest metropolis in terms of corporate headquarters and total bank deposits – a rather worrying fact when we consider the region’s history of natural disasters.

This kind of unchecked development usually results in many serious structural and social problems (Italian journalist Vittorio Zucconi once said that if Rome had the same population it would quickly turn into another Calcutta… I mean, Kolkota). Yet, while not exactly a paradise on Earth, Tokyo has brilliantly managed to avoid many of the ills of intense urbanization. It may be polluted and congested, but has a relatively low crime rate, an efficient public transportation network, and friendly neighborhoods.

Architecture in Japan is renowned for its consistent high quality and precision finishing, the result of across-the-board discussions and coordinated teamwork. That’s why in the last 30 years Tokyo has become a go-to place for many architectural lovers.

Particularly central Tokyo (the 23 special wards which comprise what until 1943 was Tokyo City) might be the first place in the world to function as a laboratory for experiments in the urbanized future of mankind. This ‘total city’ never ceases to change and reinvent itself, with buildings and sometimes entire neighborhood suddenly disappearing and being replaced but something completely different.

Constantly reshaped by man-made and natural disasters and the workings of the real-estate market, nothing is sacred and anything goes.

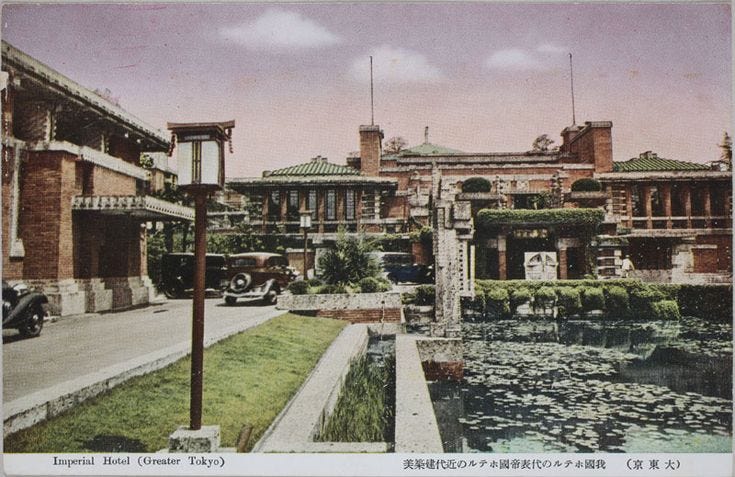

Only in Tokyo, after all, a masterpiece like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel could have been unceremoniously knocked down after surviving a major earthquake and the war.

The Imperial Hotel during its heyday.

The facade and entrance and the reflecting pool in front of the building were saved and moved to the Meiji-Mura architecture museum near Nagoya, where they can be seen today.

In the following video, you can admire the Imperial Hotel in its heyday in the mid-30s (starting from 3’17”).

Tokyo is a place that elicits strong reactions. It is impossible to remain indifferent: you either love it or hate it. The same thing can be said about its look. In many respects, Tokyo could be called the most beautiful ugly city in the world.

First-time visitors are likely to undergo visual trauma as they experience a city that spreads everywhere in a seemingly chaotic way that people who are used to more traditional notions of urban design find difficult to grasp. In Tokyo, randomness rules. Without anything resembling urban planning and zoning laws, a recognizable form or a clearly defined skyline, this city excels in the details, and it is a place where the parts are always more in focus than the whole.

As some observers have noticed, the only accepted norm is unplanned coexistence.

The labyrinthine character of this city (most Japanese streets have no name and the Japanese address system has been devised to drive people crazy) is such that losing your way is easy and in a sense even desirable. It’s much more fun to wander around without a guide book or even your smartphone, get lost and find new unexpected marvels and oddities behind every corner (without fear of being mugged or worse) including outstanding or bizarre constructions that have nothing to do with their surroundings.

Many years ago, I was taking a walk around the school where I taught when I went down a narrow backstreet, turned a corner and found this. It’s a technical college, by the way.

This is also true for residential housing (particularly two- or three-story private homes), a field in which young upcoming architects have the opportunity to experiment and put new ideas into practice.

The cityscape of Tokyo is remarkable for its almost complete absence of built continuity.

The very small and the colossal follow one another in an alternation of glazed, aluminum and concrete surfaces. At night, then, lighting transforms Tokyo into a fantastical apparition of artificial, electric mountain ranges and deep canyons.

It takes time, but eventually you realize that Tokyo, far from being chaotic, is divided in different ecosystems. Tokyo, in other words, is not a city of space, like most Western urban entities, but a city of situations; an agglomeration of villages or specialized neighborhoods, each one with its own distinctive character, each one devoted to a particular trade (musical instruments in Ochanomizu, kitchen utensils in Kappabashi, textiles in Nippori, second-hand and rare books in Jinbocho). People gravitate toward a certain district according to their interest or shopping desires.

It seems that throughout the 20th century, at 20-year intervals, events of epochal proportions have heavily affected the look of Tokyo. In 1923, for instance, the old, traditional city dating back to the Edo period (1603-1867) was almost completely destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake that killed more than 140,000 people, destroyed 570,000 homes and left almost two million homeless.

The reconstruction work that followed in the 1920s and ‘30s offered a unique opportunity for redesigning the city according to a modern, more rational approach, but in the end nothing came of it. However the government financed an ambitious plan for residential building that resulted in 16 new settlements called Dojunkai (Mutual Profit Association): modern three-story condos built in reinforced concrete around a courtyard. Then in the 1930s, the Modern Movement was responsible for a series of striking architectural works marked by sober functionalism such as Yoshida Tetsuro’s Central Post Office headquarters (still standing to this day. See below).

The Central Post Office and Tokyo Station (on the left) dwarfed by the area’s skyscrapers

Twenty years after the earthquake, another disaster – this time a man-made one – struck the Japanese capital when a series of American air bombings flattened the reborn city once again. A fourth of the city for razed to the ground, half the houses were destroyed, and 250,000 people died. Yet, Tokyo rose once again, even though this time the government placed quantity over quality in order to supply demand for residential housing. This period of frantic reconstruction culminated in the completion, in 1958, of the 333-meter tall Tokyo Tower – a veritable architectural giant in a city where at the time even the tallest buildings did not exceed eight or ten stories.

As much as I love the Tokyo Tower, it is and will always be an orange-and-white giant pylon.

In the 1960s, Japan put aside past customs and aesthetics and adopted radical modernization. Tokyo became a marketplace and laboratory willing to embrace new ideas and technology without stopping to ponder the negative side-effects of such a choice, looking to the future instead of relying on its past tradition. In this respect, the 1964 Olympic Games served as a great stimulus for redevelopment. The authorities wanted to show the world what Japan had achieved since the war.

Tokyo became known as the city of the future because it wasn’t afraid of experimenting and embracing the new, even at the cost of doing away with tradition and risking failure.

In the 1960s, for instance, the Metabolist group of visionary architects was dreaming of houses in the sky, residential units that could be put on a truck and moved anywhere one wanted, and floating cities. Tange Kenzo, in particular, unveiled his Tokyo Plan for 15 Million Inhabitants, calling for the expansion of the city out over the bay through gigantic structures to be built over the water.

The foreign community of architects and assorted creatives began to take notice. Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky saw the still young Tokyo Metropolitan Expressway (created for the Olympic Games) as a vision from the future and came all the way from Europe to film long, hypnotic, dream sequences for his 1972 work, Solaris.

Ten years later, Ridley Scott would make Blade Runner, modeling his 2019 Los Angeles after a very contemporary Shinjuku with its million lights and advertisements, and giant video screens showing inviting almond-eyed women.

Again, 20 years after the Olympics, the economic Bubble brought unprecedented levels of prosperity and unleashed a plethora of ambitious projects, with new office and commercial structures becoming the face of Japan’s economic boom and dramatically altering the face of Tokyo. On one side, corporate clients demanded flashy structures that both served as an advertising tool and attracted clients. On the other side,

many architects embraced the extreme exaggeration of post-modernism, designing buildings where quotation, simulation, collage and imitation – conveniently sold to their clients as freedom of design – were the new key words.

With seemingly unlimited budgets and almost complete freedom, they came up with the most baroque, logic-defying creations. Even someone like Kuma Kengo, who is now famous around the world for his wooden structures and whose stated goal is to recover traditional Japanese architecture, in 1991 was responsible for M2, a building that could be mistaken for a love hotel, where Western elements – especially a massive, six-story high Ionic column – were transformed into pure kitsch.

The ultimate in show-off architecture was represented by foreign-led projects. Thanks to the strong yen, local companies were able to invite famous Western architects to produce ever-flamboyant creations. Typical examples are the works by Nigel Coates and Philippe Stark. The former one was given the chance to erect two buildings next to each other: the Penrose Institute of Contemporary Arts and The Wall. The Penrose Institute – London’s ICA’s sister gallery – was probably too avant-garde, too out there for the hedonistically frivolous Nishi Azabu crowd. The building, with its four imposing Doric columns, is still there, but the art gallery has been replaced with a tamer but decidedly more welcome restaurant.

The real show stopper, though, is its neighbor: the Wall. Facing a much more austere Ando Tadao-designed building, it abruptly introduces ancient Roman history on an otherwise anonymous street. Apparently, Italian bricklayers were flown to apply the final texture, creating an artificially ruined wall. Needless to say, even this fake old building houses a restaurant.

As for Philippe Stark, he “gifted” Tokyo with a spectacular and mysterious object created for Asahi Beer, one of Japan’s main brewing companies. Standing next to their new headquarters, the Stark-designed beer hall is a black granite building topped with a 360-tonne golden flame, the Flamme d’Or, said to represent both the “burning heart of Asahi Beer” and a frothy head.

The usual suspects: from left to right, the Tokyo Skytree, the glass of beer, and the Golden Turd.

The burst of the economic Bubble not only put a stop to the extravagant building frenzy, it also brought to light the huge scale of the bid-rigging practices that had been going on for years in the construction industry. However, it never stopped the building. It only put an end to the most outlandish constructions. If anything, the first two decades of the new century have further enhanced the reputation of Japanese architects, several of whom have gone on to win the coveted Pritzker Prize, the architectural equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

All along during the last century, a constant element in this almost continuous cycle of destruction and rebirth has been the contrast between ever-changing buildings and a nearly immutable street plan dating back to pre-modern, pre-industrial times. The result is that the architects have to adapt their designs to strangely shaped blocks, often resulting in triangular and other oddly shaped structures, or the famous slim buildings that look almost two-dimensional.

Built at the tail end of the Bubble years, Marion Botta’s Watari Museum of Contemporary Art is an apt example of the way in which the client’s needs and the architect’s vision often clash with the environment where they plan to erect their building. However, in the case of the Watarium (as the museum is often called), the man-made damage dated back to a more recent event, the 1964 Olympic Games. The sports event was preceded by a period of hectic planning that resulted in many hurried decisions. In this specific case, a new road, Gaien-nishi-dori, was constructed to link Shinjuku and Shinagawa, slashing through many residential districts without regard for the narrow streets and old rectangular plots that had survived to that day. As Botta wrote in the presentation of his project, “Tokyo exacerbates the contradictions of modern cities.” This forced him to come up with “a strong and precise image that had to resist the confusion and contradiction of languages, styles and forms present in Tokyo.”

(End of Part 1)

Till next time, I leave you with some chosen Tokyo night-time dreamscapes.

Gianni - some sent this to me and it is superb, happy to dig through your archive.

One element of Tokyo architecture I find fascinating is the mix of serene (that traditional aesthetic) and visual pollution (signs and neons and all manner of stuff). It is unique in blending those elements on a massive scale.

Nice article. Thorough research. Having moved out of Tokyo to seaside area, I still often come to Tokyo as a “tourist” and enjoy it.