Ready for part 2?

Nowadays, Tokyo looks like a shapeless blob trying to contain an ever-expanding human community. Its population reached one million in 1884. Irresistibly attracted by the seemingly endless opportunities the capital offered, more and more people kept pouring in. 30 years later, at the time of the disastrous earthquake, four million called Tokyo their home; in 1941, when Japan declared war to the United States and Great Britain, the population had already ballooned to over seven million. The Pacific War brought death and destruction, but by the time the 1964 Olympic Games celebrated the country’s return to the world stage, Tokyo already boasted over 10 million people. Today, the Tokyo Metropolis that in 1943 replaced Tokyo City has 13 million residents, and some two million buildings are squeezed inside its central 23 wards where nine million Tokyoites live.

Everybody seems to know Shibuya Crossing, but these videos are always fun to watch

Tokyo presents a bewildering array of modern architecture which has been built almost entirely from the beginning of the 20th century. Widely (and wildly) divergent styles and scales exist side by side among a confusing clutter of signs, vending machines and overhead power lines. At times, the visual and aural onslaught is unbearable. Particularly in the commercial districts, the streets have so much visual information that the environment seems indecipherable.

Even in the suburbs, you can’t escape the spiderweb of overhead power lines

In this constantly re-forming metropolis, buildings have always been treated as disposable objects, easily demolished or replaced, following the simple, straightforward logic of economic interest. Why waste a prime piece of land on a beautiful, historically and culturally important nine-story or – god forbid – three-story building (e.g. Frank Lloyd Wright’s old Imperial Hotel) when we can erect a 20- or 30-story skyscraper and sell all that office and residential space to businesses, shops, restaurants and tenants.

The concept of culture preservation is unknown in Japan, especially when it comes to modern architecture.

Many aspects of local culture are overlooked, even denigrated by the Japanese until they are discovered and praised abroad. Only then the Japanese start regarding their own culture with different eyes. It happened to ukiyoe prints when Japonism became in vogue in France, and it happens every time an artist or film become successful in Europe or America.

The same thing can be said about archiving. Public institutions have the bad habit of discarding any item that according to their narrow point of view is not deemed worth keeping. Photos, documents, artifacts, etc. anything goes, unless someone inside that institution is particularly devoted to preserving them for the sake of the future generations.

In architecture, one of the main battles currently going on is between property speculators and conservationists, with the latter group desperately trying to save a number of important buildings.

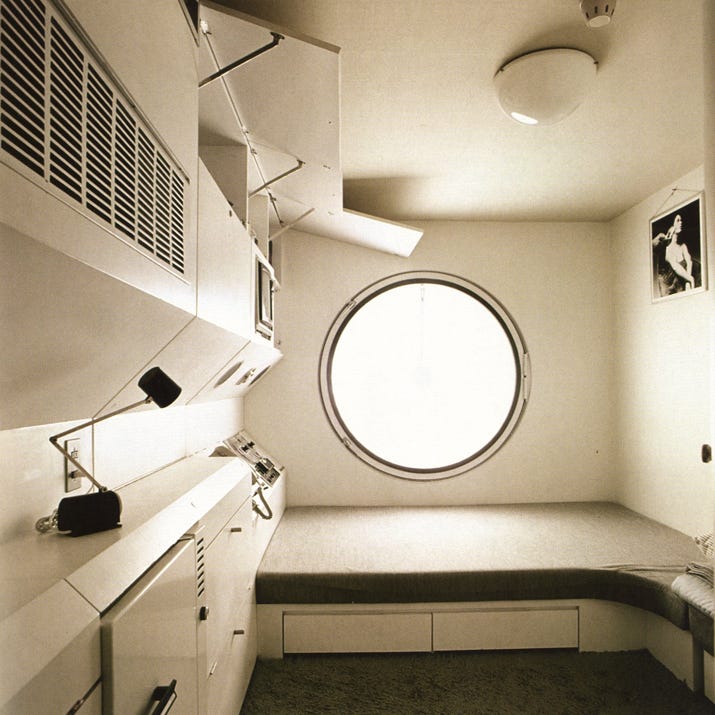

Take the Nakagin Capsule Tower. Even today, this tall pile of boxes with round windows looks quite impressive. Not everybody likes it, but personal tastes aside, for many years this creation by the late Kurokawa Kisho represented one of the very few Metabolist projects that did not remain on paper but were actually realized.

However, if you want to take a closer look you will have to hurry because, like many other historical buildings, its days may be numbered. Built in 1972, it was conceived like a sort of biological organism whose cells (tiny apartments only ten square meter wide) were theoretically flexible and interchangeable as they could be moved to other similar sites.

50 years on, the structure has not aged very well. The original units/cells should have been replaced 25 years ago. Instead, they are still there, clinging to a rusting central tubular structure. Currently there is a hardly fought battle going on between those who want to save it and those – including most owners – who want to tear it down and replace it with a new building.

Unfortunately, the Nakagin Building is just one of many such cases. In fact, more than one hundred historical buildings are at risk of being demolished, according to DOCOMOMO Japan, an association belonging to an international organization that since 1988 is fighting to protect important architectural works. The main problem is that the Japanese government is traditionally more than happy to back the developers’ interests. For example, a new law that was promulgated in 2002 further liberalized city planning, partially doing away with building height and location wherever a new project included a park.

The developers, for their part, seem to be free from any kind of sentimentalism or nostalgia for the past. Every time they have to choose between renovating a historical building (which means replacing all the electric and mechanical features) and erecting a brand-new structure, they invariably choose the latter option.

The sad result is that in the last 20 years one historical building after another has succumbed to their ax. In Tokyo alone, just to give a few example, in 2007 Mitsui Fudosan tore down the Sanshin Building, an elegant construction dating back to 1930 that was famous for its splendid entrance hall that featured an ornate ceiling and many small decorative details.

In 2009 it was the Sofitel Tokyo Hotel’s turn. Facing Ueno Park, this hotel stood up thanks to its unusual shape inspired by both the Tree of Life and traditional Buddhist temples.

Even the Dojunkai condominiums I mentioned in Part 1 are no more. Built between 1924 and 1934 and easily recognizable thanks to their beautiful ivy-covered walls, quite incredibly all of them survived the air raid, but they couldn’t escape the developers’ bulldozers. The very last one was demolished in 2013, but the most famous among them, the one in Aoyama, had already been disposed of ten years earlier to be replaced by Omotesando Hills, a pretty unremarkable creature – part shopping mall, part luxury apartments – made of concrete and glass stretching for 250 meters along Omotesando avenue.

Omotesando before: the Dojunkai

Omotesando after: Ando Tadao’s bland corporate Omotesando Hills

If the Dojunkai had been located in Europe or America, they would have likely opted for adaptive reuse – reorganizing and improving the original structure in order to keeping the old look while adapting the interiors to modern needs. Alas, Mori Building apparently found this solution too complicated and time-consuming. Eventually, a tiny fragment of the Dojunkai was preserved for old times’ sake.

It has to be noted that this lack of empathy for historical buildings does not even spare famous architects. Frank Lloyd Wright, for instance, realized five projects besides the Imperial Hotel. However, only two of them survive to this day. As for his ill-fated hotel, you can still admire its entrance and the central portion at Meiji Mura, an architectural museum near Nagoya.

Detail of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel

Back to our list of excellent victims, the Hotel Okura was closed in 2015 for major renovation. Since 1962, it was considered one of Tokyo’s classier hotels (it’s not by chance that James Bond stays here in Ian Fleming’s You Only Live Twice). The new version was unveiled in 2019 – a 38-story glass tower (18 of them devoted to office space) where, interiors aside, nothing has been left of its past charm.

Hotel Okura’s snazzy 60s vibe.

According to German architect Ulf Meyer, the real problem lies in the fact that

Tokyo is the only city in the world where any piece of land is about ten times more valuable as anything anybody could ever build on it.

Considering this premise, no work of architecture can have any claim to last. Therefore, Japanese architects can never aspire to build lasting monuments.

In the end, Tokyo is an ephemeral city that never seeks permanence. It is forever incomplete.

Defining such a place remains extremely difficult. Tokyo can hardly be judged or appreciated by applying some of the parameters we typically use when we look at a city. Think about Rome, Paris, London or New York and there are some images that immediately come to mind; places and monuments that have come to symbolize them and contribute to their myth.

Now think about Tokyo.

I bet you would be hard pressed to come up with a definite image. The stereotypical impression that people get by reading articles and books or watching TV programs is a jumble of buildings and signs and colors without a definite order or direction. Tourist postcards usually feature a rather underwhelming skyline (West Shinjuku) or a sea of ferroconcrete with a weird orange-and-white pylon in the middle – the Tokyo Tower. When, in the 1980s, the above-mentioned Italian journalist Vittorio Zucconi was sent here to work as a foreign correspondent, he looked down from the window of his airplane and was reminded of a room in which a kid had just scattered on the floor several boxfuls of building blocks. It was a polite and imaginative way to say that Tokyo was, after all, an ugly city.

What unique landmarks can Tokyo boast about? Take, for example, the Tokyo Tower. Imagine the Eiffel Tower, but slightly different in shape. The Japanese version is 330 meters high that is 30 meters higher than the French tower. Unfortunately, it’s been painted white and red (well, technically it’s called “international orange”). The overall effect is totally different: the ever-proud French have turned a mountain of iron bars into a national symbol. The Japanese have turned the same amount of iron into a giant pylon.

More recently the Tokyo Tower has been overshadowed by the much higher Tokyo Skytree. The Big Toothpick?! Forget it.

In the end, probably Tokyo’s most outstanding architectural feature is the vast network of roadways (see video in Part 1) that weave their way through the high-rises and over long stretches of the capital’s rivers and canals before diving underground and under Tokyo Bay.

The Expressway is unique to the Tokyo cityscape and is still very much a work in progress nearly 60 years after the first section was completed in 1962 – again in preparation of the Olympic Games. Originally conceived to connect all the Olympic venues, it was quickly seen as a practical way to solve central Tokyo’s unmanageable traffic congestion.

I mentioned rivers and canals. Tokyo used to be full of beautiful waterways along which people did business and enjoyed themselves. Alas, today many of them are literally overshadowed by the Expressway (it was built on top of them in order to avoid paying landowners) and make for a very sad sight. Still, other small rivers were even more unlucky for they were filled or turned into culverts.

The Tokyo Expressway was built over the Nihonbashi River and the historical bridge from which all distances in Japan are calculated.

When dealing with Tokyo, we probably have to take the good and the bad because they are inextricably connected. In any case, whatever opinion you have about the city, Tokyo never allows you to take her for granted, and it is this ever-changing chaos that hides most of the city’s charm. It seems that here things are allowed to grow, develop, change and die according to a natural inner rhythm, like a living organism, in which beauty is to be found in the easily overlooked small things.

The combination – sometimes the clash – of new and old and the ceaseless input of new cultural imports from around the world give the city an energy you can hardly find elsewhere. It’s the excitement of urban culture in the process of constant creation and reinvention.

I hope this one-two architectural punch was worth the wait. For those of you who live in another Japanese city or abroad, how does your place compare to Tokyo?

If you are new to Tokyo Calling, please look around. You may be interested in reading about the Beatles in Japan, a traditional geisha district, or my close encounter with COVID-19.

And be sure to subscribe to get all the stories delivered to your email address.

And I thought Sydney lacked empathy for its historical buildings! Interesting article, Gianni, although it makes me sad to think that historical and modern can't co-exist in cities like Tokyo and Sydney.