Engines of rebellion: Bōsōzoku and the global language of youth subculture

How biker subcultures from Tokyo to Marseille reveal the global struggle over identity, conformity, and freedom

Dear readers, my latest Japan-related discovery is Japanese Modernity @ Substack, a newsletter by academic historian Christopher Gerteis (SOAS University of London). Lots of food for thought to exercise your inquisitive minds.

Here’s Gerteis sensei’s take on bosozoku, a subject I find endlessly fascinating.

Be sure to scroll down to the end of the post - there’s more interesting information and videos.

In the 1960s and 70s, the roar of motorcycles echoed through the streets of Tokyo, Los Angeles, Melbourne, and Marseille—not just as noise, but as a declaration. Across the globe, young people found in motorbike culture a way to resist, to belong, and to define themselves on their own terms. Yet the meanings of rebellion differed dramatically by place. The motorcycle was never just a vehicle. In the hands of the disaffected, it became a symbol of movement, escape, and resistance—a loud, defiant answer to lives mapped out by others.

Global biker subcultures reflected the interplay of social, economic, and political factors that shaped their distinct identities. In Western Europe, biker culture leaned more toward sport and leisure, with riders favoring touring motorcycles and participating in organized racing events (Brake, 2013). Unlike their counterparts in other regions, European bikers were less overtly rebellious and more focused on camaraderie and competition. This contrasts sharply with the biker subcultures in the United States and Australia, where motorcycles symbolize freedom, rebellion, and nonconformity (Weight, 2013).

Japan’s bōsōzoku subculture offers a compelling case for comparison, highlighting how local contexts shape identity formation and rebellion. Emerging during the postwar period, the bōsōzoku rejected societal norms and capitalist industrialization's expectations, embracing instead a transient agency amidst Japan’s rapid economic transformation. By carving out spaces of freedom through the roar of their heavily modified motorcycles, the bōsōzoku expressed a form of playful self-actualization that defied Japan’s rigid educational and employment systems. Their rebellion against conformity mirrored the ethos of other biker subcultures globally, yet their motivations were deeply rooted in Japan’s socio-economic landscape.

Bōsōzoku: Identity Formation and Rebelliousness

The bōsōzoku reflected the socio-economic dynamics of postwar Japan. Police statistics and sociological data suggest that the majority of bōsōzoku from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s came from blue-collar families in urban centers. These families, which had achieved middle-class status due to Japan’s economic boom, found that their children faced limited prospects within an extremely competitive state education system. For these youths, the bōsōzoku offered a means of self-definition outside the confines of societal expectations.

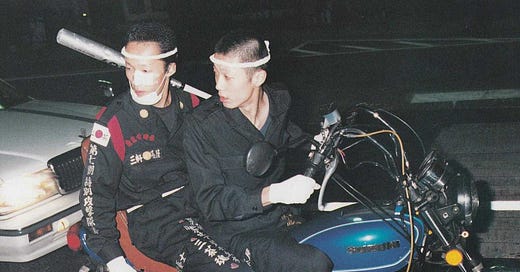

Unlike their counterparts in Europe or North America, the bōsōzoku’s rebellion was not primarily about individualism but about creating an alternative form of community. Their flamboyant uniforms—combining military attire, worker’s jumpsuits, and school uniforms—and their elaborately customized motorcycles symbolized a rejection of Japan’s rigid social hierarchies. Their identity was also shaped by their neighborhoods, often in blue-collar urban areas where their presence became a cultural force. This reflected not just rebellion but also an articulation of frustrations tied to Japan’s postwar industrialization.

This reflected not just rebellion but also an articulation of frustrations tied to Japan’s postwar industrialization.

The rejection of societal norms by the bōsōzoku was not only a personal choice but also a symbolic act reflecting broader societal issues. Their actions embodied a critique of Japan's intense focus on academic success and career achievement, which often left little room for individuality or creative expression. Bōsōzoku gangs created a space for members to redefine success on their terms, measuring it by loyalty to their group and their ability to live outside mainstream expectations. This sense of purpose was amplified by their public displays, such as illegal street races and noisy parades, which defied the quiet orderliness of Japanese society. These acts were not merely disruptions but declarations of agency, showcasing the ways in which marginalized youth could assert control over their lives in a rapidly modernizing world.

Social Representation and Media Influence

The media played a significant role in shaping public perceptions of the bōsōzoku. Newspapers and television often sensationalized their activities, portraying them as delinquents and potential gangsters. This portrayal emphasized their use of weapons, such as wooden swords and Molotov cocktails, and their illegal street races, reinforcing stereotypes of chaos and criminality. These media representations echoed the treatment of biker subcultures in other countries, such as the Mods and Rockers in Britain, whose conflicts sparked a moral panic during the 1960s (Barnes, 2011). However, in Japan, this sensationalism also served as a mechanism of state control, further alienating the bōsōzoku from mainstream society. Media coverage didn't merely reflect public anxiety—it produced it, transforming localized acts of defiance into national spectacles.

The 1964 seaside riots between Mods and Rockers in Britain provide a revealing parallel. As Weight (2013) notes, the riots were widely reported as existential threats to British society, though they often involved only a handful of participants. Similarly, the bōsōzoku’s illegal street races and loud public displays were inflated in the media to symbolize broader fears of youth rebellion and declining moral standards. In both cases, the media played a dual role: stigmatizing these subcultures while amplifying their allure among disaffected youth.

Media portrayals often failed to capture the complexity of the bōsōzoku subculture, reducing its members to caricatures of violence and rebellion. These representations ignored the nuanced motivations driving many young people to join these groups, including a desire for community, recognition, and a means of navigating societal exclusion. By sensationalizing bōsōzoku activities, the media inadvertently strengthened their allure among disaffected youth, who saw in these gangs an opportunity to assert their identities against a backdrop of societal indifference. Moreover, this media-driven narrative blurred the lines between cultural expression and criminal behavior, making it difficult for mainstream society to engage with the underlying causes of bōsōzoku defiance (Sato, 1991).

The Interplay of Political Power and Self-Image

Political power profoundly influenced the self-image of bōsōzoku members. As the Japanese state sought to impose social control on this subculture, it branded the bōsōzoku as ‘bad youth,’ equating their rebellion with delinquency. This labeling was a strategy to contain their defiance, as their expressions of freedom clashed with the state’s vision of youth as disciplined contributors to capitalist productivity. The harder the state cracked down—through police repression and legislative measures—the more intense the bōsōzoku’s defiance became.

The perceived association between the bōsōzoku and Japan’s far-right groups further complicated their social image. While some commentators saw them as potential recruits for ultranationalist movements, many bōsōzoku resisted political affiliations altogether. Their rebellion was less about ideology and more about asserting individuality in a system that prioritized collective conformity. This resistance is reminiscent of the Mods’ rejection of postwar austerity in Britain, where their consumerism and sartorial elegance were seen as subversive acts against the conservatism of the 1950s (Barnes, 2011). At the heart of this tension lies a paradox: the more society tried to erase the bōsōzoku, the more vividly they etched themselves into the cultural imagination.

At the heart of this tension lies a paradox: the more society tried to erase the bōsōzoku, the more vividly they etched themselves into the cultural imagination.

Global Context of Biker Subcultures

The global spread of biker subcultures illustrates how youth movements adapt shared themes of rebellion, identity, and mobility to their specific socio-cultural and political contexts. While the Japanese bōsōzoku developed uniquely in response to postwar industrialization and social hierarchies, their core values resonate with subcultures elsewhere. Biker movements in Western Europe, North America, and Australia all share a rejection of societal norms and a pursuit of freedom. These subcultures, however, differ in their manifestations, reflecting the distinct economic conditions, cultural values, and political environments of their regions. The interplay between local and global influences highlights the complexity of biker subcultures as both universal and deeply localized phenomena (Brake, 2013).

In Western Europe, biker culture leaned heavily toward sport and leisure, often eschewing the overt rebelliousness found in other regions. Riders in countries like France, Germany, and Italy embraced touring motorcycles and participated in organized racing events, emphasizing camaraderie and technical skill. This contrasts with the bōsōzoku in Japan, whose emphasis on style, noise, and public disruption set them apart. Yet, the European focus on group identity and the shared experience of riding finds parallels in the bōsōzoku’s communal ethos. Both movements reflect a desire to form alternative communities in response to mainstream societal pressures, even if their methods of expression diverge significantly (Hebdige, 1979). No matter the region, these movements leveraged mobility and spectacle to critique the status quo. A motorcycle wasn't simply a machine—it was a protest on wheels.

A motorcycle wasn't simply a machine—it was a protest on wheels.

Despite their differences, these subcultures demonstrate a shared use of mobility and aesthetics as tools of resistance. The customization of motorcycles—whether the choppers of American bikers, the cafe racers of British Rockers, or the exaggerated fairings of the bōsōzoku—serves as a form of self-expression that challenges societal expectations. The global resonance of these movements underscores their ability to adapt universal themes of rebellion to local contexts, offering young people a means of navigating and resisting the constraints of their environments (Sato, 1991).

Legacy and Reflection

The bōsōzoku, like biker subcultures across continents, remind us that resistance often begins in the margins—among those least empowered to shape society, yet most eager to redefine it. Their flamboyant aesthetics and defiance continue to inspire cultural narratives, reflecting the enduring significance of subcultures as spaces of identity and resistance. As Barnes (2011) observes, such movements are vital for understanding how marginalized groups navigate the pressures of modernity while asserting their individuality. The legacy of the bōsōzoku is not merely a tale of rebellion but a testament to the ways in which youth culture shapes and reshapes society.

One of the most striking aspects of the bōsōzoku’s legacy is their influence on Japanese popular culture. Even as active membership in bōsōzoku gangs declined, their distinctive style and ethos left an indelible mark on manga, anime, film, and fashion. Works such as Akira (1988) and Tokyo Revengers (2021) drew heavily on the bōsōzoku aesthetic, portraying gang members as both antiheroes and cultural symbols of rebellion. This romanticized image of the bōsōzoku—complete with roaring motorcycles, exaggerated uniforms, and a staunch loyalty to one’s group—transcends its historical origins to serve as a broader metaphor for individuality and resistance against conformity. In fashion, elements of bōsōzoku style, such as embroidered jackets and bold, militaristic designs, have periodically resurfaced in Japanese streetwear, demonstrating the subculture’s ongoing relevance as a source of creative inspiration.

However, the bōsōzoku’s legacy is not without complexity. While they are celebrated in cultural narratives, their history also reflects the tensions of a society grappling with rapid economic transformation and the alienation it produced among its youth. The bōsōzoku embodied the frustrations of Japan’s blue-collar class, whose economic advancements in the postwar boom often failed to translate into upward mobility for their children. These young people, caught between a growing affluence and rigid societal expectations, found in the bōsōzoku a space to resist and redefine what it meant to succeed. This duality—of rebellion as both resistance and self-expression—highlights the significance of subcultures in articulating the unspoken struggles of marginalized groups. At the same time, the decline of the bōsōzoku into the 2000s underscores how subcultures, while influential, remain vulnerable to the pressures of state intervention, media stigmatization, and economic shifts.

As youth movements evolve, the bōsōzoku serve as a lens through which to examine broader questions about generational identity, agency, and resistance. Their story is a reminder that subcultures do not exist in isolation but are deeply intertwined with the socio-economic and political structures of their time. The bōsōzoku’s rebellion against Japan’s rigid hierarchies parallels similar movements across the globe, from the Mods and Rockers in Britain to the outlaw motorcycle clubs of North America and Australia. These parallels underscore the universality of youth subcultures as responses to alienation and societal pressure, even as they remain uniquely shaped by their local contexts. By preserving and studying the legacy of the bōsōzoku, we gain a richer understanding of how youth cultures influence and challenge the broader societal narratives that seek to define them.

Further Reading

Barnes, R. (2011). Mods!. Omnibus Press.

Brake, M. (2013). The sociology of youth culture and youth subcultures: Sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll?. Routledge.

Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. Routledge.

Sato, I. (1983). Crime as play and excitement: A conceptual analysis of Japanese bōsōzoku. Tohoku Psychologica Folia, 41, 64–84.

Sato, I. (1991). Kamikaze biker: Parody and anomy in affluent Japan. University of Chicago Press.

Weight, R. (2013). Mod: From bebop to Britpop, Britain's biggest youth movement. The Bodley Head Ltd.

To cap it all, you may want to check out God Speed You! Black Emperor (1976), a Japanese black-and-white documentary film by director Mitsuo Yanagimachi that follows the exploits of a bosozoku gang known as the Black Emperors. There are no subtitles but it’s well worth a look (you can skip the boring bits) as it offers a different look at Japanese society during a period when the bosozoku phenomenon was reaching its peak. (For historical precision, bosozoku membership peaked in 1982, with over 42,000 members).

Or you may prefer this shorter video by Vice Magazine (with English subs).

Here's a comment from a Japanese friend:

"Good report. This is my high school days. I remember some friends join the teams: Spector, Black Emperor, Itsunboushi etc. They sprayed their own name on the walls. Modified bikes go on the street with noisy sound all night long.

A few readers have complimented me for this story. Please notice that the author is Christopher Gerteis, not me. And be sure to check out his newsletter!