Dear readers, my older and more loyal fans will remember that I caught Covid-19, a few light-years ago. Well, it seems we are now living in a post-mask age, or something like that. On March 13, the government announced the easing of mask-wearing guidelines, with the decision on whether to wear masks to be left up to individuals in most situations. It’s not that even before that date people were fined for not wearing a mask, mind you. It’s just that now I can finally walk outdoors unmasked without attracting dirty disapproving looks.

So does that mean that the Japanese are finally showing their faces in public after more than three years? Not so fast. You see, the government said that “it’s up to each person to decide whether to wear a mask or not,” and the Japanese just HATE to decide for themselves, individually. It’s much easier to do what everybody else does. I mean, what’s wrong with the herd mentality? After all, there’s safety in numbers. Which, inevitably, means that most Japanese are still wearing masks.

Today it was a nice, sunny, warm day, so I went for a long walk across Tokyo and after two hours I had only seen a bunch of people not wearing a mask - all of them guys, by the way. I firmly believe that women are more intelligent than us, but in this particular department, we beat them hands down. Sorry.

Anyway, as a personal bye-bye to those filthy masks, I’m reprinting part of an article on the history of face masks in Japan that I found a couple of years ago in The Japan Times. I hope you’ll enjoy the pictures.

Covering the mouth with paper or the sacred sakaki (Japanese cleyera) leaves to prevent one’s “unclean” breath from defiling religious rituals and festivals has been common from ancient times and is a custom still observed at Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto and the Otori Grand Shrine in Osaka, among others. During the Edo Period (1603-1868), the practice seems to have penetrated a significant portion of the population.

This multicolored woodblock print shows kimono-clad patients receiving treatments from people who appear to be a masseuse, an acupuncturist and a doctor. This nishiki-e dating from the Edo Period depicts a scene of a medical clinic. If you take a close look, you’ll see one of the patients covering his mouth with what appears to be a piece of cloth.

The modern history of masks begins in the Meiji Era (1868-1912).

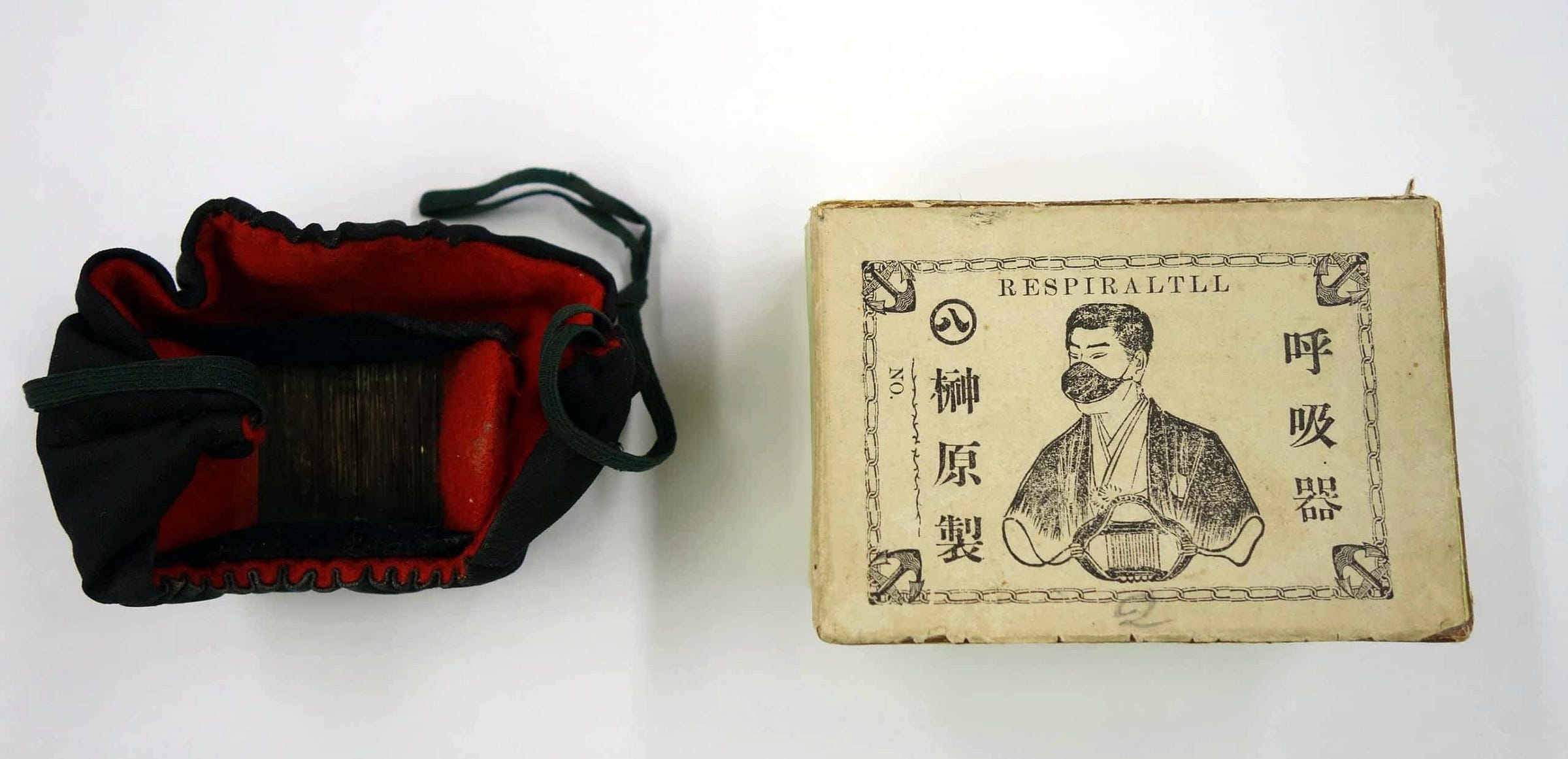

Initially imported for mine, factory and construction workers, facial masks back then featured outer shells made from cloth fitted with brass wire mesh filters [like the one in the photo used as the banner for this post, which shows also its original box adorned with a retro-chic illustration of a man wearing a mask with the inscription RESPIRALTLL]. In 1879, one of the first domestically produced masks was advertised in newspapers.

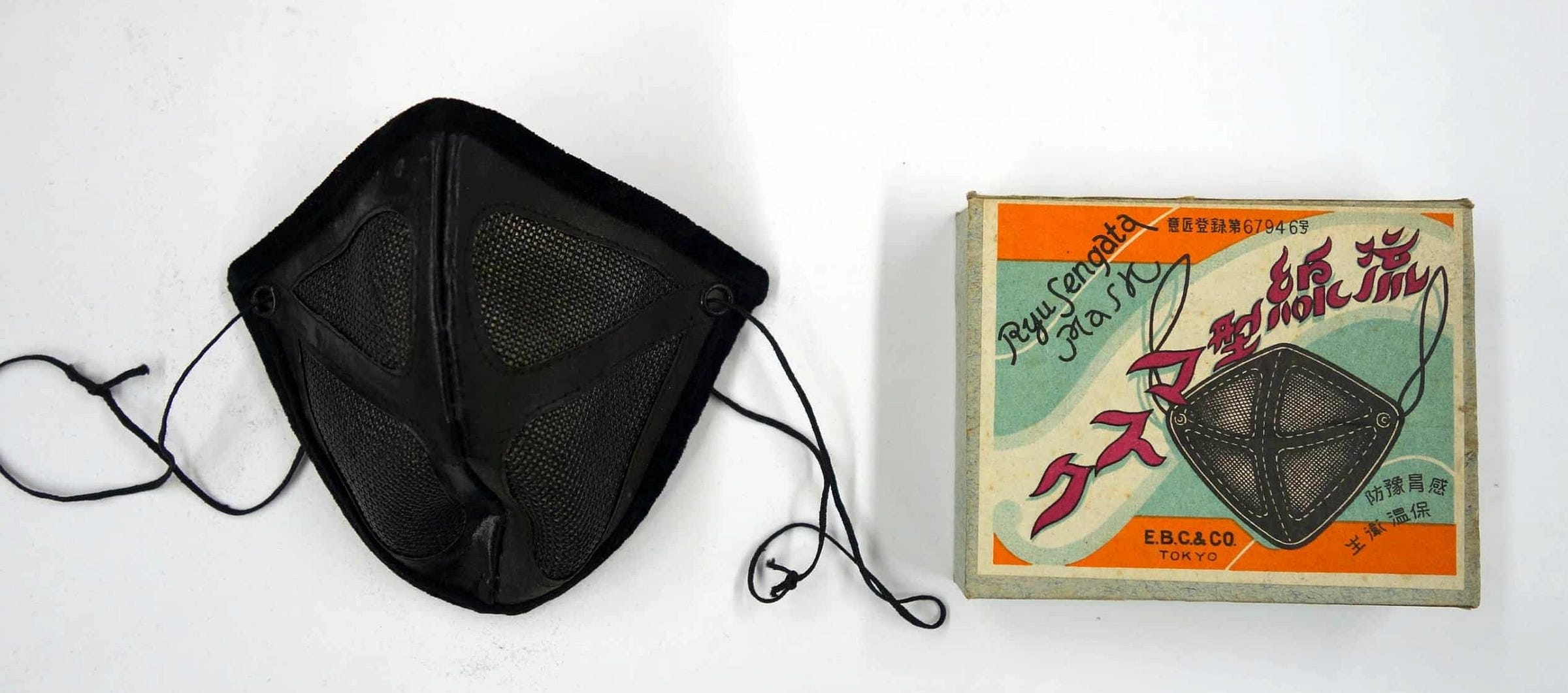

Celluloid gradually overtook metals to become the material of choice for the mesh filters. Costing around ¥3,500 by today’s standards, these weren’t cheap and were made to be reused after replacing the gauze sheets, sold separately, that were inserted between the mouth and the mask.

The mask business flourished during the Taisho Era (1912-26) as the economy boomed with factories filling orders from Europe in the throes of World War I. Numerous products made from leather, velvet and other materials advertised under various brands inundated the market.

The single most important event that elevated masks from being a luxury item to an everyday product for the masses was the Spanish flu, which killed tens of millions around the world between 1918 and 1920.

In Japan alone, 450,000 perished according to some estimates, with an additional 280,000 believed to have died on the Korean Peninsula and in Taiwan, which were under colonial Japanese rule at the time.

Saburo Shochi, a famously long-lived academic, was often interviewed about his experience during the pandemic.

In a story that ran on Nikkei Medical in 2008, the 90th anniversary of the start of the Spanish flu outbreak, Shochi recalled losing his classmates to “the bad cold.” Shochi said most of his family, including himself, then around 10 years old, caught the disease and were unable to get out of the futon for days. The infectious nature of the virus eventually became known, and people started wearing masks, which seemed to offer protection from the influenza, he said.

Educational posters from the period feature slogans such as “reckless are those who don’t wear masks.” And for those who couldn’t afford to buy masks, newspapers began giving instructions on how to make them at home, much like the online mask-making tutorials that flourished during Japan’s latest mask shortage.

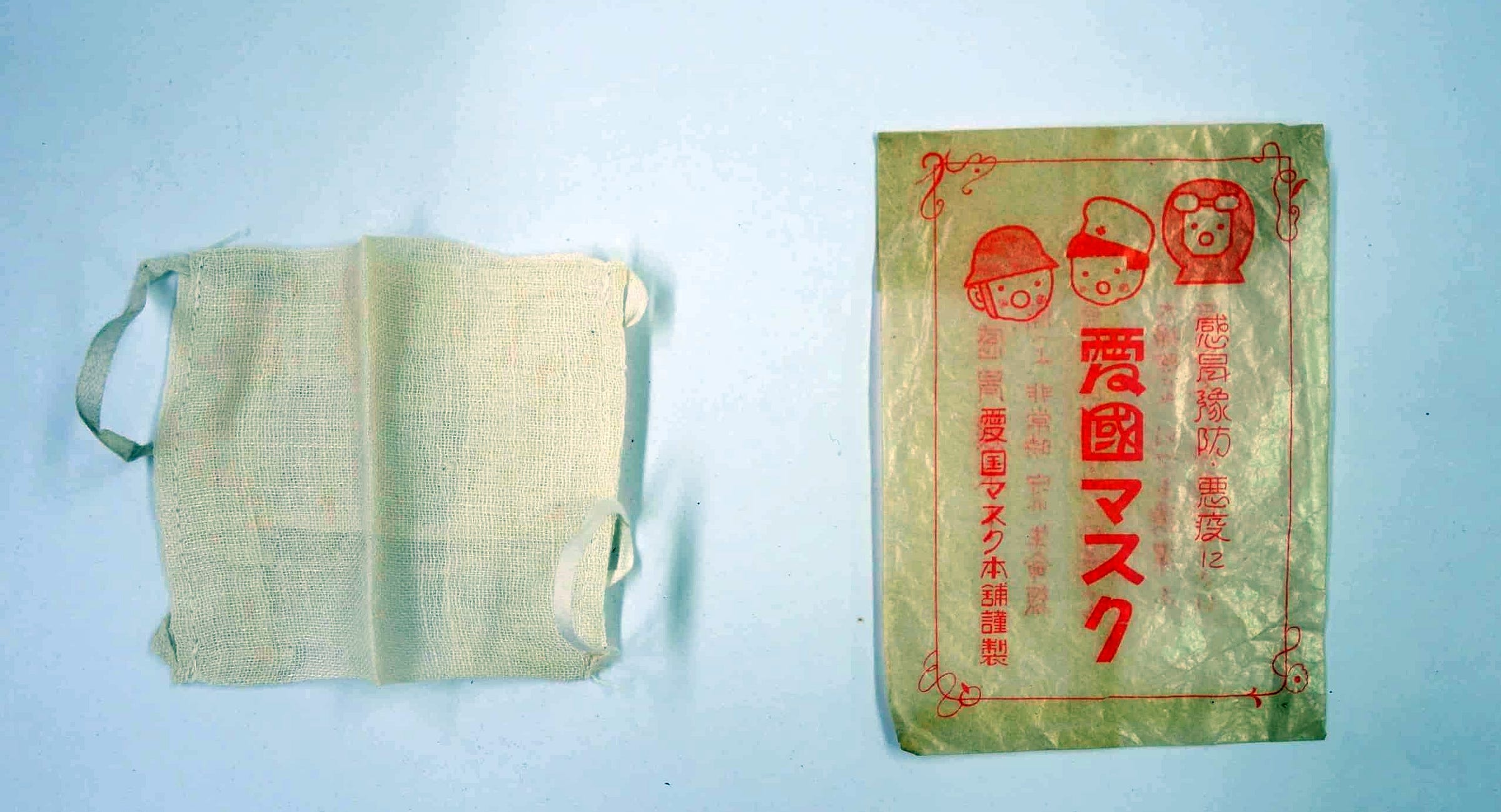

During the early part of the Showa Period (1926-89), masks similar to today’s three-dimensional models were produced (see above), but shortages arose during World War II when raw materials were reserved for the military. Simple and cheaper gauze masks became the norm. By the end of the war, the face mask — once a symbol of affluence — was reduced to a piece of gauze with strings attached.

In the postwar years, masks gradually evolved into the current form, with white, disposable, nonwoven pleated masks becoming mainstream.

This evolution of masks is thought to be something quite unique to Japan.

The above-pictured mask bears the words aikoku masuku (patriot mask).

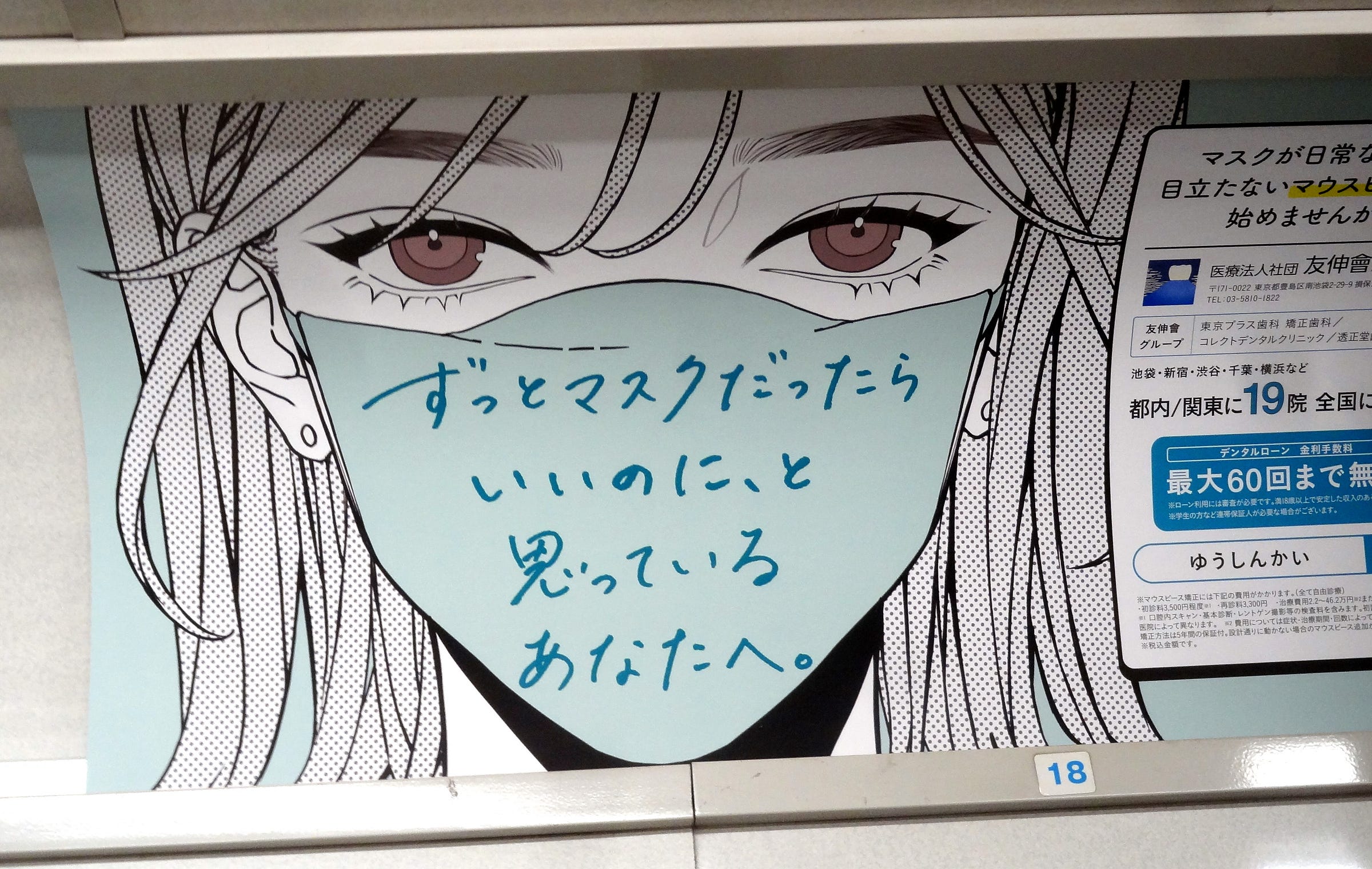

Herd mentality apart, some people (mainly women) interviewed on TV said that they feel safe hiding their face behind a mask, and for this reason, they may continue to wear them even now that the emergency is over.

I took a photo of this advertisement inside a subway car. It says, ”For those like you who want to wear a mask forever.”

I still see wearing masks while driving alone in a car...

Interesting article and really enjoy (as always) the images! In my years living in Hong Kong before the pandemic (but after SARS), there was a ton of mask wearing already, albeit only the surgical mask variety. Sadly, a lot of my students were pushed off to school by parents with a mask when they really should have stayed in bed! But there were benefits: I remember wearing them at several doctor's offices, no doubt helping me avoid illness well before I understood the use on a COVID pandemic level.