When talking about Godzilla, we cannot leave out the nuclear issue. After all, Godzilla’s creation was heavily influenced by a real-life incident that reminded everybody of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I talked to Yamamoto Akihiro about postwar Japan’s contradictory attitudes toward nuclear energy as shown in popular culture and the Godzilla series in particular.

Yamamoto is an associate professor in the Department of General Culture at Kobe City University of Foreign Studies. He specializes in modern Japanese history and media cultural history and has written extensively about the nuclear issue in Japan including the book Kaku to Nihonjin: Hiroshima, Gojira, Fukushima (Nuclear Power and the Japanese: Hiroshima, Godzilla, Fukushima, 2015).

In the immediate postwar period, the atomic bomb and nuclear energy were symbols of overwhelming power in Japan, but few people spoke about the risks they posed.

After the war, Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, so all information was subject to censorship. For example, researchers from Tokyo, Kyoto, and Kyushu University studied radiation exposure in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, the information was held by GHQ and the results were only revealed after the occupation ended. In other words, between 1945 and 1952, talk about nuclear energy was only allowed if it was seen positively. This inevitably determined people’s attitudes on this issue. They had no access to reliable information about its negative aspects. For them, it symbolized how science could lead the world to a bright future.

In fact, the whole world seemed to share this attitude. Immediately after Japan lost the war, negotiations were held at the United Nations between the Soviet Union and the United States on how to manage nuclear energy. There were strong expectations for the United Nations to help use the atom in a peaceful way. As you know, that did not happen, but the fact remains that at the beginning of the postwar period, people’s opinions were influenced by the international situation (including censorship), and the faith in science and progress.

In your book, you show how this had a concrete impact on Japanese pop culture.

Nuclear energy appears in manga and anime in two different ways. On one side, it is used as a symbol of great strength and destructive power. For example, in Fukui Eiichi's judo manga Igaguri-kun, which began serialization in 1952, the protagonist's rival uses a special move called the “atomic bomb throw.” To the readers, however, this name does not convey any negative imagery. The 1951 manga Brother Pikadon by Shabana Bontaro is another example. In this work, the protagonist is called Pikadon because he turns everything upside down when he panics. However, pikadon is also slang for the atomic bomb, but in those stories, the tragic memories of the A-bomb are nowhere to be found.

The other way in which the use of nuclear energy is portrayed is how it makes a character stronger. The best-known example, of course, is Tezuka Osamu’s Astro Boy. However, during the occupation, there were similar stories that predated Tezuka’s work, like Chojin Atom and Atom Shonen, in which the protagonist has the power to defeat sumo wrestlers. The scientific explanation for his strength is that he was exposed to the atomic bomb, so the nuclear bombing was transformed into a positive event.

I think there were two types of nuclear fears after the war: the fear of nuclear war and the fear of nuclear testing. How did Japan's attitude toward them change?

For the Japanese, the Korean War, which was fought right next to our country, was a huge event. Only five years had passed since the end of the war, but General MacArthur was talking about the possibility of using the atomic bomb against China. Then, in 1952, Japan regained its sovereignty. This allowed for free speech, and many people became aware of nuclear energy’s negative aspects. Regarding nuclear testing, which is also the basis for Godzilla’s birth, this was a time when the US and the UK were conducting nuclear tests in the South Pacific, and Japan was clearly against them.

As for nuclear war, the biggest factor in the 1950s was Sputnik, the first artificial Earth satellite, which was launched by the Soviet Union in 1957. The fact that the Russians succeeded in launching an artificial satellite meant that they could launch missiles too. In 1945, planes had dropped atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but now they only needed to push a button to hit a faraway place. The situation reached its peak with the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. That was also the time when the peace movement in Japan gained momentum.

Godzilla, released in 1954, was called the hydrogen bomb monster because it’s the story of a Jurassic dinosaur driven from its habitat by repeated hydrogen bomb tests. Abe Kazunosuke, who designed Godzilla’s first version for this film, even proposed a head shaped like a mushroom cloud, and the monster’s distinctive skin is said to have been inspired by keloid scars. What impact did the film have on Japanese people?

It certainly had a strong influence on Japanese audiences. It can be viewed as the nuclear issue’s dark side. Astro Boy represents the bright side of the nuclear future while Godzilla symbolizes its destructive power and Japan’s tragic past. The monster attacks Tokyo at night, and those scenes are a clear reminder of the 1945 air raids. After all, only nine years had passed since the end of the war.

The second important point is the radiation that Godzilla emits. As you know, it is directly inspired by the Bikini nuclear test and an incident in which a Japanese fishing boat was exposed to fallout radiation.

Godzilla successfully embodied the fears that many people shared at the time. It is also a really well-made movie, better than the filmmakers thought it would be. It's no wonder that it became a big hit.

Another noteworthy thing about the film is that when Godzilla comes, America doesn't help at all, while Japan’s Self-Defense Forces are no match for the monster. In the end, what defeats Godzilla is a new weapon devised by a Japanese scientist. In later decades, people would question the negative effects of scientific progress, but in the 1950s, Godzilla’s ending resonated with the feelings of many Japanese people.

Let’s jump forward to the 1980s. The 1984 film The Return of Godzilla signaled a return to Godzilla's scary origins. However, when the monster attacks a nuclear power plant, no real damage is done. On the contrary, Godzilla absorbs radiation and converts it into energy. This trend continued in the following films up to Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995). What is your take on this new Godzilla era?

As you pointed out, after the cute and child-friendly phase in the decade between the mid-1960s and mid-70s, Godzilla was remade to be a threat to humanity. I find that having the monster absorb radioactive material and turn it into energy is a very Japanese thing to do. On one side, the producers wanted to make a scary movie. However, they didn’t want to highlight the damage caused by radiation because they mainly aimed at entertaining people. Furthermore, Japan had – and still has – a lot of nuclear power plants, so I guess they wanted to avoid showing the nuclear industry in a negative light.

I would say that we can divide the Godzilla series into three main phases: the scary 1954 era, the 1980s, and the new cycle started by Anno Hideaki's Shin Godzilla in which again, the monster is a runaway nuclear power plant.

In 1986, a nuclear accident occurred in Chernobyl. Even so, public opinion in Japan did not move significantly in favor of abolishing nuclear power. Why was that?

The short answer is that for many Japanese, Chernobyl seemed far away. Actually, after the Chernobyl disaster, there was a great surge in public opinion against nuclear power, but it was short-lived. I would say it lasted for about two or three years. There are several reasons for this. For one thing, the anti-nuclear movement mainly arose in music and countercultural circles. Popular rock musicians began to add emotional messages in their songs, so in a sense, the anti-nuclear message was consumed as a trend. The Japanese economy was also doing very well, and the anti-nuclear messages became commodities in youth consumer culture.

Of course, the anti-nuclear movement relied on mass media such as rock magazines, manga, etc. Now, Emperor Showa died in January 1989, and the local media entered a phase of self-restraint. This sudden silencing of the means to spread anti-nuclear opinions also caused the movement to wither and shrink.

Also, as I mentioned, it was the period of the economic bubble, so there was a fear that if nuclear power plants were stopped, Japan's growth would come to a halt. This is a very important point when considering nuclear power as a theory of civilization though it is difficult to say whether nuclear power plants are related to economic growth. Of course, the nuclear lobby insisted that for the economy to grow, nuclear power plants were indispensable.

As you mentioned, Godzilla’s third important era started in 2016 when Shin Godzilla was released. In this film, the monster was also seen as a metaphor for the 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima.

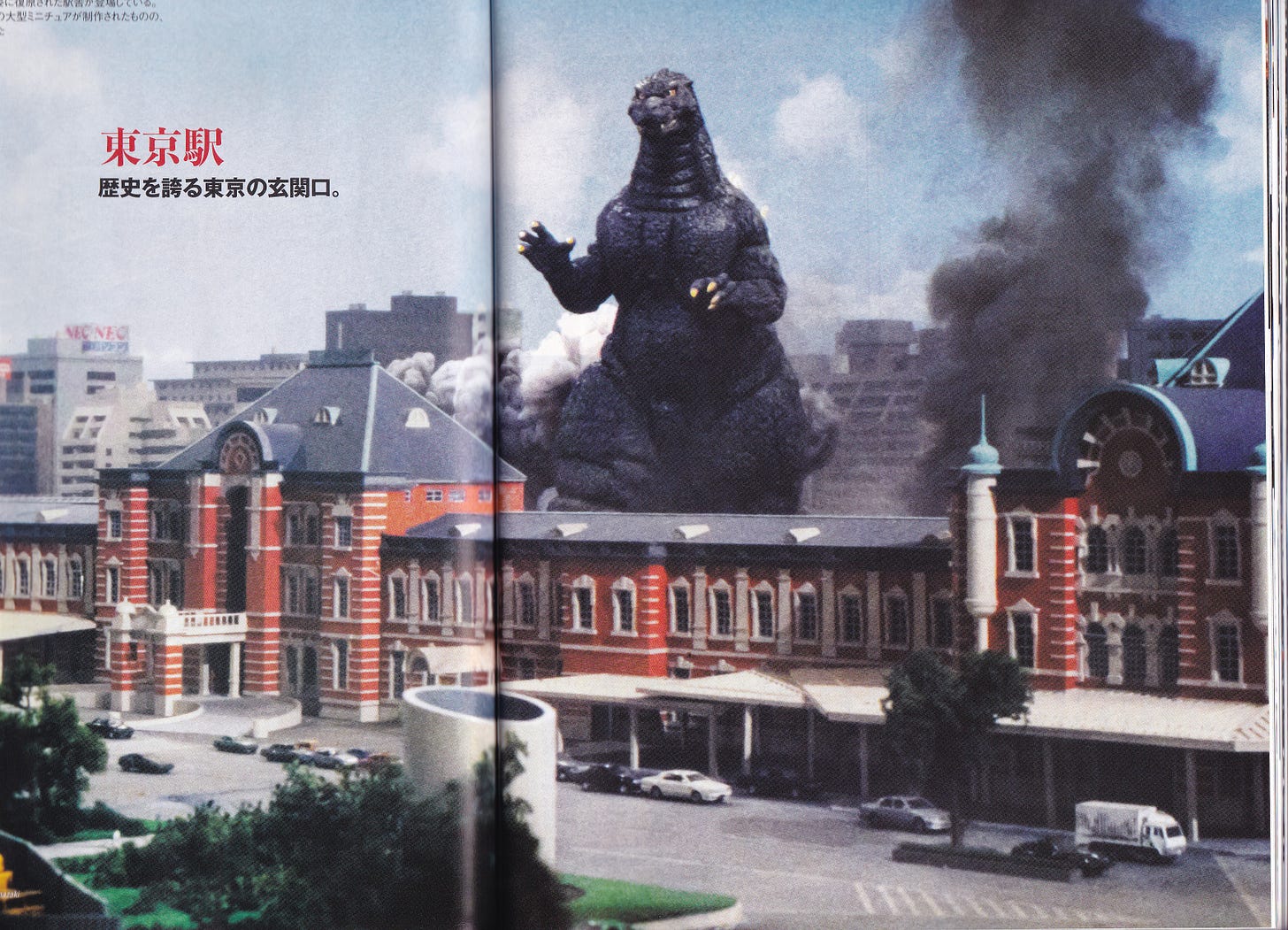

Fukushima was clearly in director Anno’s mind. Think about the last scene: Godzilla is finally frozen and stopped near Tokyo Station. However, it's not clear if and when it will be able to move again. I think anyone who watched Shin Godzilla in 2016 was reminded of a nuclear power plant that hadn't been shut down yet. It’s just a metaphor for the ongoing drama in Fukushima. As a matter of fact, to this day, it's not over yet. In this respect, the director was sending a strong message.

At the same time, it is explained in the film that the radioactive material scattered by Godzilla has a very short half-life of 20 days, and its effects on the human body will disappear within about two to three years. Don’t you think that’s not a very realistic view of radiation?

It’s the same problem I pointed out about the films from the 1980s. It would be shocking if Godzilla, frozen smack in the middle of Tokyo, continued to emit radiation. The production company probably decided that saying that it would be impossible to enter Tokyo and the Kanto region for a long time, like Chernobyl, would be too depressing, so they easily dismissed the effects of radiation on the environment. Again, that’s typical of Japanese thinking. They point out the problem, then they try to downplay its implications.

In Shin Godzilla, they also focus on the possible use of nuclear weapons (i.e. whether to nuke Tokyo or not) in order to destroy the monster. To me, the striking thing is that they speak more directly and emphatically about this subject than in any other Godzilla film.

To be sure, in the past they never discussed the eventuality of the United States dropping a nuclear bomb on Japan. The notable thing to me is that the debate only features politicians. In both the original Godzilla and the 1984 film, a larger part of society was involved. In Shin Godzilla, on the contrary, all the talk is limited to the government and the Self-Defense Forces as if only the elites' point of view was worth showing.

Don’t you think that even after Fukushima, public opposition to nuclear power was a little weaker than expected?

Indeed, after such a big accident, I was expecting more. Now, after just ten years or so, nuclear power plants are operating normally again, and people are talking about whether another earthquake will come or not. It shows how difficult the situation is in Japan. This country is obsessed with the myth of economic growth. We can't stop nuclear power plants, otherwise many people will lose their jobs, so we have to put up with the pressure from the business world.

It's a kind of disease, a negative legacy of postwar Japan: the idea that we can’t slow down but have to become richer and richer.

What those people are saying is that rather than thinking about the future, it's okay to enjoy the present, and whatever happens later, well, we'll be already dead.

Who knew Godzilla was so layered? I've shifted my perspective, not only on Godzilla but also on King Kong, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, etc, from 1D 'comic' creations to metaphors of the political kind.