Gotanda’s Balancing Act: Between the Polished and the Profane

Walking Meguro to Gotanda (3)

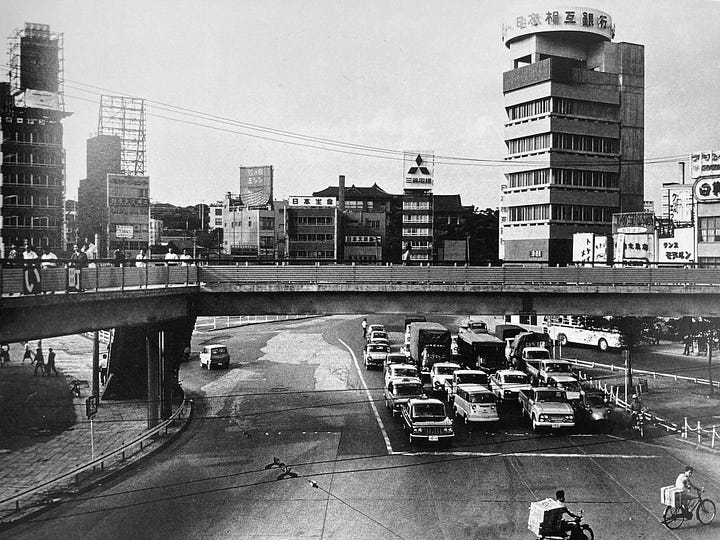

Gotanda yesterday and today.

Gotanda is one of those stations that most people breeze through without a second thought – more a junction than a destination. Even now, well into the 21st century, this neighborhood is the epitome of architectural anonymity. But back in 1982, it was having a bit of a moment. Sony, the undisputed rockstar of global electronics at the time, had its headquarters here, and the area enjoyed a mini boom. Office towers went up, karaoke bars multiplied, capsule hotels appeared – it was Gotanda’s shot at the big time. And then… time sort of stopped.

In Tokyo’s corporate world, prestige is everything. Companies flock to neighborhoods with the right cachet, places that look good on a business card. Look at what’s happening in Shibuya. Somewhere along the line, Gotanda fell off the “cool” map, and the investment dollars went elsewhere. Sony itself decamped to Shinagawa in 2006, leaving behind only a tech center like a polite goodbye note.

Still, there’s a certain retro charm to Gotanda’s time-warped business district, dotted with manufacturing firms and surprisingly leafy residential pockets. It’s got grit, it’s got history, and there’s always the Meguro River’s comforting presence.

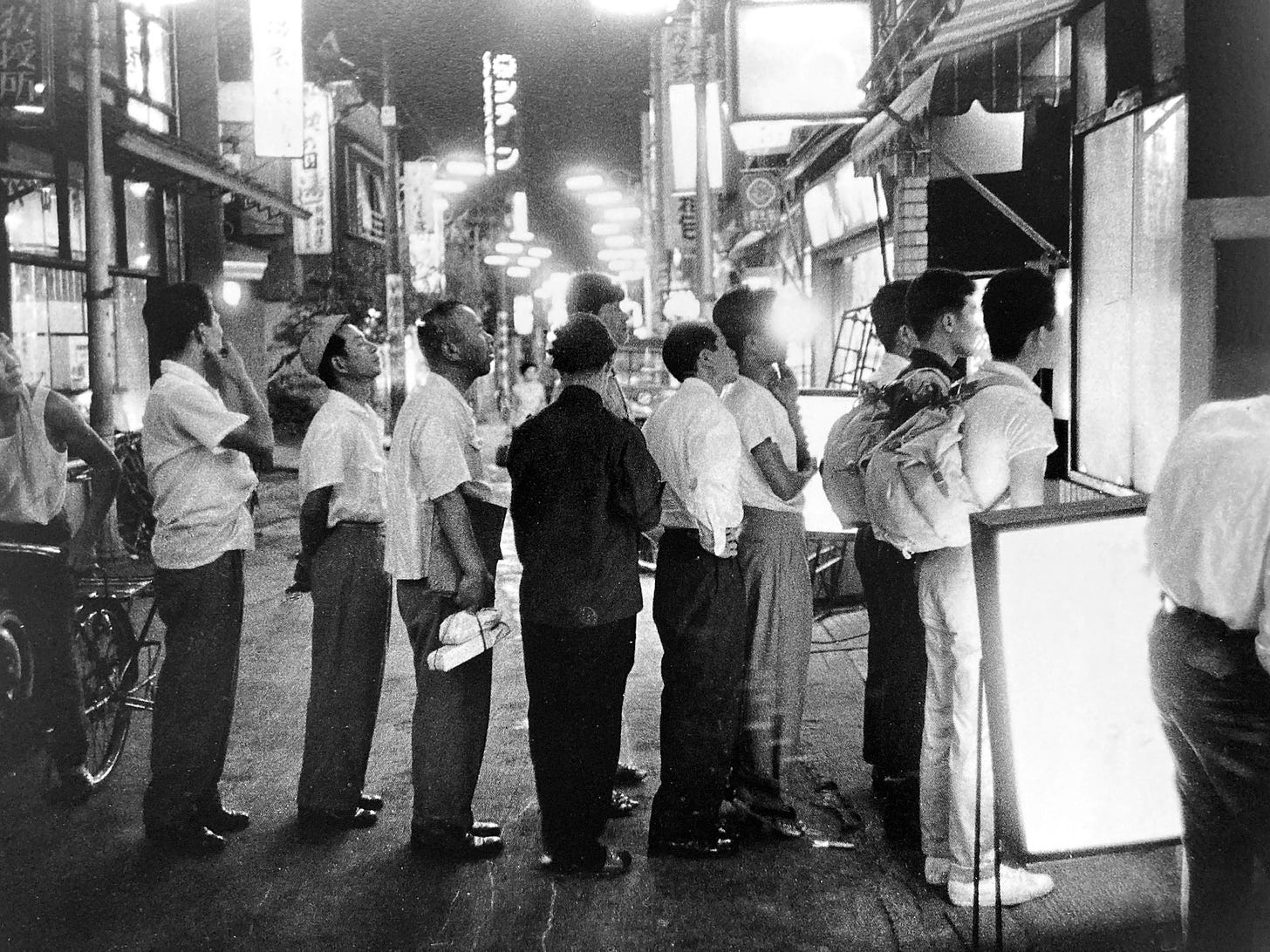

The 80s were also a time when Gotanda became well known in Tokyo for its concentration of love hotels, adult video shops, and nightlife businesses. This area was not originally a red-light district like Yoshiwara or Kabukichō. Instead, it grew as a transport hub along the Yamanote Line, with factories, office buildings, and modest commercial activity. But its location – convenient to Shinjuku, Shinagawa, and central Tokyo – made it attractive for discreet nightlife businesses.

The love hotel boom coincided with rapid urbanization and small-space living. Gotanda, with relatively affordable real estate compared to Shinjuku or Shibuya, became a hotspot for such establishments. By the late 1970s, guidebooks and tabloid-style magazines began publishing maps of love hotel districts, and Gotanda consistently had its own section.

With the growth of the AV (adult video) industry, Gotanda became a well-known center not only for consumption (video rental shops, sex-related businesses) but also for parts of production and distribution. This reputation was reinforced by the clustering effect: once a neighborhood became associated with such businesses, others followed.

Today, redevelopment has softened some of these edges. Office towers and chain hotels dominate the station’s east side, while the west side has pockets of sleek restaurants and startups. Yet Gotanda’s lingering reputation as one of Tokyo’s “love hotel towns” still endures, though it’s not as flashy as Shibuya’s Dogenzaka or Ikebukuro’s backstreets. In this sense, it sits at the intersection of transportation convenience, urban redevelopment, and the less “official” sides of city life.

I make a beeline for the TOC Building, said to be one of Gotanda’s best spots. The name stands for Tokyo Oroshiuri Center – oroshiuri meaning wholesale. Completed in 1970, the building was developed by Hoshi Pharmaceutical, a company whose main claim to fame is its Hoshi gastrointestinal medicine, popularly known across as “Hoshi’s Red Can.” Backed by government support, the TOC was part of an effort to ease commercial congestion in the Nihonbashi district.

At its peak, the TOC Building buzzed with the energy of some 7,700 workers spread across offices for nearly 380 companies. The basement alone was a mini city, packed with eateries offering every kind of cuisine. There was also a post office, a medical clinic, and even a bank – all the essentials for an entire workday without ever stepping outside. A massive parking garage could accommodate up to 1,000 cars.

The building was a true commercial hub, with each floor dedicated to a specific category of goods: women’s ready-to-wear, menswear, accessories, fabrics, lingerie, smoking paraphernalia, and glittering displays of gold and silver jewelry. Though these were primarily wholesale showrooms, many vendors were happy to sell directly to walk-in customers, making the TOC something of a hidden treasure trove for bargain hunters.

But the moment I step inside, it’s clear something’s off. The building’s glory days are long behind it. In the 54 years since it opened, the TOC has lost much of its former shine. A relic of the Showa era, it doesn’t just look gray – it feels gray. Many of the restaurants and shops have shuttered, and those that remain are more about practicality than pizzazz. Empty spaces abound, and 閉店 (closing down) signs are everywhere. SALE SALE SALE. WE ARE CLOSING. The message couldn’t be louder.

And yet – I love this place. Wandering its corridors, I notice that each floor has its own personality: different color schemes, motifs, and striping patterns. You can almost picture how dazzling it must have been in the 1970s, bustling with buyers and merchandise. On the 12th floor alone, there are 60 retail spaces, but only about ten are still occupied. Before long, it feels like you are on the set of The Shining or Dawn of the Dead – minus the zombies.

Unfortunately, the roof is now off-limits. Too bad. It used to feature a strange coupling: a golf-driving range and a Shinto shrine. From there, you could also glimpse the distant hills where some of Tokyo’s most exclusive estates are nestled, including the neighborhood once home to the Shoda family—former Empress Michiko’s own.

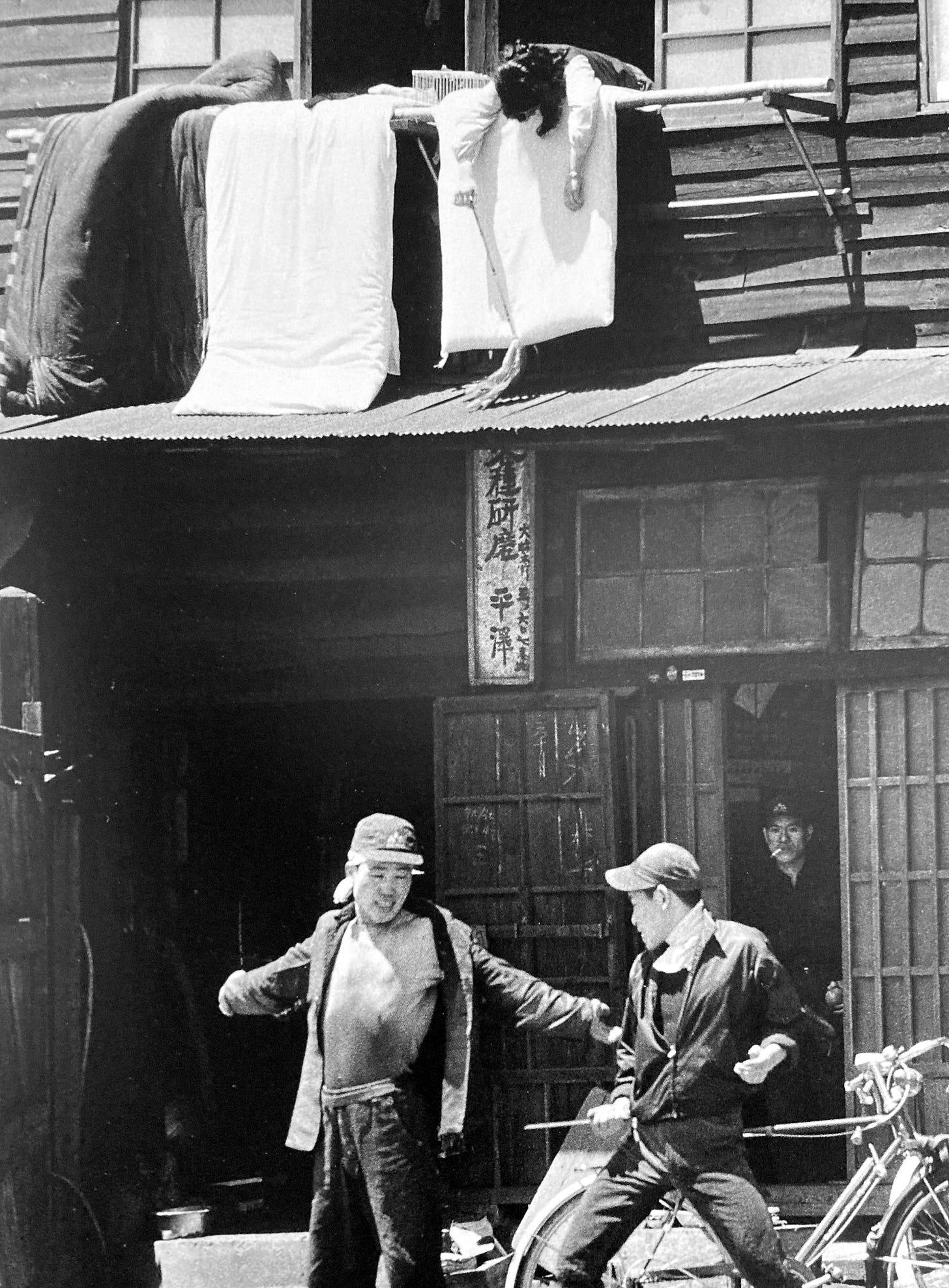

As a PS, the photo above gives me the chance to mention the kumosuke. Originally, this term referred to itinerant laborers - porters, palanquin bearers, or ferrymen - who operated along highways and post stations during the Edo period. These workers were often unregulated or moguri (unofficial), and some gained a reputation for predatory behavior, including overcharging travelers, extortion, or even theft.

The nickname kumosuke may derive from their tendency to lurk like spiders, waiting to trap vulnerable customers.

One notorious tactic they used was to look at the customer’s feet: if a traveler’s sandals were worn out, signaling they couldn’t walk further, the kumosuke would jack up the price, knowing the customer had no choice.

This practice gave rise to the idiom “ashimoto o miru” 足元を見る, now used to describe taking advantage of someone’s weakness.

In more recent times, kumosuke became a derogatory term for unscrupulous taxi drivers who overcharge or mistreat passengers. The term has sparked legal and social backlash, especially when used in public discourse. For example, a comedian and a judge both faced criticism for using it to describe taxi drivers.

Great post, Gianni. The images, especially the first 3-4, are amazing and compliment your words beautifully.

Nice. Thank you. I also liked “ashimoto wo miru”. Kind of “looking for Achiless’ heel “.

Want to revisit Meguro river. Don’t remember if I can walk from Shimbamba to Gotanda or even starting earlier at Tennozu Isle. But believe doable…