You can read Part 1 here.

And don’t forget the special 80% discount on annual paid subscriptions.

$30 → $6 (see link above)

Here’s a chance to support Tokyo Calling for cheap.

People often say that Japanese culture holds a deep reverence for nature, with a special affection for trees and flowers. Yet, based on their actions, it seems to me that there's a strong desire to shape and control nature to fit their own vision.

That's another issue I’ve been thinking about a lot. One thing I find truly unique about Hidden Japan is that, to my knowledge, no other writer on Japan really talks about trees. It’s an overlooked, unspoken, almost invisible subject. In contrast, I devote considerable attention to trees in my book, introducing readers to a number of remarkable species.

Part of the reason is that trees have become the latest targets in Japan’s ongoing sterilization of public space. Trees are being cut down at an alarming rate—not just along city streets, but also in parks, universities, hospitals, and other public areas. It’s widespread and quite extreme. Just look at what’s happening in Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Gaien: the redevelopment plan there is set to remove nearly a thousand trees to make way for high-rise buildings and revamped stadiums. It’s shocking, and it's not just Tokyo. Even in my small town of Kamioka, the same thing is happening.

The perception now seems to be that trees are dangerous or obsolete. They’re considered messy—shedding leaves, attracting bugs—and therefore unwelcome. Even trees that have stood for centuries are being removed. I can’t think of another developed country where this would be tolerated.

A Japanese friend once remarked that all the things people say about Japan’s love of nature are still true—if you just add -ta to the end. That is, they were true. In the past.[In Japanese, the suffix -ta is added to a verb to make the past tense.]

By the way, I’ve just completed writing the Japanese-language sequel to Hidden Japan. We explore six more locations, and in one chapter, we travel to Aomori in search of Japan’s great trees.

Of the many places you wrote about, was there one that left a particularly strong impression on you, for any reason?

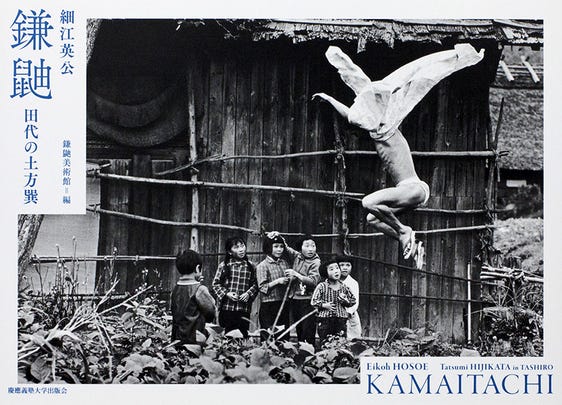

One that truly stood out as both unusual and thought-provoking was Tashiro, a small village in Akita Prefecture. It’s the birthplace of Butoh, the avant-garde form of Japanese dance theatre that emerged in the late 1950s. Butoh arose as a radical response to both traditional Japanese performing arts and Western influence, and one of its pioneers, Hijikata Tatsumi, was born in that very region.

Visiting Tashiro sparked a deeper curiosity about Tohoku, Japan’s northeastern region. I found myself wanting not just to revisit it, but to immerse myself more fully in its landscape, history, and particularly its Jomon-era roots. Tohoku really is “hidden Japan”—less traveled, less written about. It’s home to vast stretches of untouched rice paddies, old thatched farmhouses, and some of the country’s most evocative festivals and shrine dances.

Tashiro itself is captivating. The small Butoh museum there is a gem—a perfect introduction to the dance form—and I’d encourage anyone with an interest in performance or culture to visit. But more than that, it offered me a gateway into what I’d call “Deep Tohoku,” a region that still retains layers of Japan’s ancient spirit.

[The collaboration between photographer Hosoe Eikoh and Butoh founder Hijikata Tatsumi in Akita Prefecture produced the iconic photo series Kamaitachi. This series, created between 1965 and 1968, captures Hijikata performing in the rural landscapes of Tashiro, Akita, embodying a mythical weasel-like spirit known as the kamaitachi. The images are surreal and haunting, reflecting themes of postwar trauma, folklore, and the tension between tradition and modernity.]

I’ve visited a couple of the places you wrote about in your book. In 2021, for example, we did a special on rice production and culture, which took me to the Noto Peninsula.

You were fortunate to see it when you did—so much of what you captured is now gone because of the earthquake. Do you remember, in my book, the photo of Nushi-no-Ie, the House of the Lacquerware Merchant, with its every surface coated in that beautiful, semitranslucent lacquer? It burned down, completely destroyed. Even Kuroshima, the historic port once bustling with kitamae-bune merchant ships that sailed the Sea of Japan coast, suffered heavy damage. And Wajima, of course, was hit especially hard.

The other place I visited, just this past January, was Shiga Prefecture. When I spoke with Governor Mikazuki about their tourism strategy, he mentioned a strong focus on experiential and educational tourism. What’s your take on that? Do you think it’s a good direction?

Absolutely. For years, I ran a traditional arts initiative called the Origin Program, where we introduced international visitors to cultural practices like the tea ceremony, Noh theatre, and more. As you know, in recent years there’s been a huge surge in inbound tourism—Japan has become one of the most sought-after destinations in the world. And with that, there’s been an explosion of experience-based offerings: from cooking classes and Zen meditation to dressing up as a samurai, a maiko, or even a ninja—whatever you’re into.

So yes, it’s already happening, and with great success. I read recently that a surprisingly large portion of what foreign tourists spend in Japan now goes toward these kinds of immersive experiences. From crafts to spiritual practices, the possibilities are practically endless.

The last thing I’d like to ask you about is the “rewilding” of the Japanese countryside. What exactly do you mean by that?

What’s happening is that Japan’s rural areas are being depopulated at an astonishing rate. The birthrate is low, and young people continue to leave for the cities. As you know, Japan’s overall population is shrinking—by more than 800,000 people just last year. That’s a staggering figure, and most of that decline isn’t happening in the cities but in smaller towns and rural villages. The smaller the town, the faster it’s disappearing. Tiny villages across the country are vanishing. Hundreds of them. Many will be gone in five to ten years. In some cases, they’re already effectively gone. The buildings may still be standing, but the people have left.

As a result, rice paddies and farmland are being abandoned, overtaken by weeds, vines, and wild growth. Nature is returning—and along with it, wildlife. Japan is now teeming with deer, wild boar, monkeys, bears, foxes, rabbits—you name it. In one sense, it’s an environmental recovery, a rewilding of sorts.

But here’s the problem: the rewilding happening in Japan isn’t necessarily a good thing. In Europe, rewilding is a highly scientific and deliberate process. Ecologists and land experts assess original ecosystems, reintroduce native species, manage water flow, and restore vegetation with precision. It’s a carefully managed effort.

In contrast, Japan’s version is largely unplanned. If you simply let nature take over without any guidance, it can become chaotic, and even harmful. Take, for example, the sugi (cryptomeria) plantations. These monoculture forests, many of which were the result of postwar forestry policies, are aging and unstable. If left unmanaged, they’ll eventually collapse. What’s needed is thoughtful intervention: cutting down the sugi and replanting with diverse, sustainable species. But that’s not what’s happening. What we see instead is unmanaged regrowth, often dominated by invasive species or the remnants of failed forestry projects.

It’s unfortunate, because rewilding—done properly—could be an environmental and social asset. But that would require major investment and a shift in policy. One of the reasons that hasn’t happened is that Japan struggles to let go. Even as villages empty out and rice farming becomes unsustainable, government subsidies and policies continue to uphold the old model. Rice cultivation is still heavily supported, despite the fact that in many areas there’s no one left to grow it. Bureaucratically and culturally, that’s a hard reality to face. The system is designed to maintain the status quo, even when the ground beneath it is literally disappearing.

That’s a rather bleak picture.

I hope this interview doesn’t come across as overly negative. Yes, there are serious issues that shouldn’t be ignored, and some truths need to be spoken. But the heart of Hidden Japan isn’t about dwelling on what’s broken; it’s about celebrating what remains. In writing this book, we set out to find places that are still beautiful, still intact. And the good news is: they exist. Japan still holds an extraordinary wealth of unspoiled places. So the message is, go out and find them, they’re out there, waiting.

As someone who lives in Shimane, where the Japanese word for depopulation (過疎 - kaso) originated in Hikimicho - now part of Masuda, I take issue with part of the rewilding complaints.

"Take, for example, the sugi (cryptomeria) plantations. These monoculture forests, many of which were the result of postwar forestry policies, are aging and unstable. If left unmanaged, they’ll eventually collapse. "

In Shimane, and the rest of the Chugoku region, all (or almost all) of these forests are still actively managed. When I go for bike rides I regularly see the foresters cutting one side of a hill or another. Short of the total depopulation of the region I don't see that stopping. We just climbed up a mountain overlooking Hikimi gorge and there were enough logging trails cut that it was a little unclear in places where the correct hikers path was supposed to go. Thanks to all the roads the ministry of concrete has built the foresters can live (do live in fact, I've had drinks with a couple) in the surviving small towns and quickly drive out every day to their mountain of interest, something that would have taken a lot longer on the roads of just a quarter century ago.

That's not to say that I don't see the abandonment of rice terraces and so on and how they are reverting to odd swamps, but I don't think that "scientific" rewilding helps. Japan is a lush enough country that everything just grows and in a few years the kuzu and other invasives will have been replaced by something else.

I think part of the reason why Japanese people, particularly those in the countryside, are fairly casual about the rewiliding of parts is that it's been a part of the Japanese way of life for centuries and they can see relics of previous eras before people moved away for one reason or another. Take Iwamiginzan, one of the largest suppliers of silver in the world at the start of the Edo-era. At that time population was IIRC estimated to be around 100,000. Now the same area has a population of maybe a couple of thousand. When you hike some of the trails in the hills around it you see all kinds of stone terraces and walls that were built maybe 400 years ago and have been disused for at least 200. Some of those terraces are being used, in fact, as Sugi plantation now and I imagine sometime in the next decade or so they'll be clear cut for the timber.

I enjoyed the read. Thank you very much for the informative piece.