I spent early January delving into Dr. Kathleen Waller’s “The City as Text.” There's so much food for thought in that wonderful essay about cities that I got stuck for days reading and exploring and checking out all the links.

By a strange coincidence, my latest piece is also about cities. It appeared a few days ago on Nippon.com. I hope you will enjoy it.

We live in a world facing several environmental challenges, from global warming and overpopulation to pollution and waste disposal. According to Azby Brown, we can learn from life in the Edo period (1603-1867) about how to create a more sustainable society.

A Gray City with a Greener Past

Azby Brown is an expert on Japanese architecture, design, and environmentalism. In Just Enough: Lessons from Japan for Sustainable Living, Architecture, and Design, he takes the readers on a trip back through time to when Tokyo was called Edo, showing us how the Japanese managed to create a less wasteful life. Many things have changed since the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but Brown believes that old-time Japan still has a lot to teach us.

“Tokyo is a heavily urbanized area,” Brown says, “the largest urban conglomeration in the world, with more than 37 million people. This, of course, creates many problems. First off, almost everything Tokyo needs—from energy to water and food—comes from outside its borders. In this sense, Tokyo has a broad environmental footprint and depends for many things on the surrounding prefectures. In 2011, for example, we saw how vulnerable Tokyo was regarding the water and power supply when the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster occurred.”

Tokyo shares several environmental problems with other urban areas worldwide, such as massive waste generation, air quality problems that affect citizens’ health, and dependence on environmentally unsound energy systems. Some of those problems may be unavoidable, but Brown points out that Edo was one of the biggest cities in the world and was densely populated, and yet in many respects fared better than Tokyo.

Asked about how Tokyo compares to similar big cities like New York or London, Brown says that both of them have more parks and green space. “We have seen better urban planning in some districts,” he says, “but overall, if you look at Tokyo from the sky, it’s fairly bleak and gray in all directions. I think the best models for a sustainable approach tend to be European cities. Many places in Germany and Scandinavia, for example, have done a lot to minimize power consumption and waste and have adopted better principles regarding greening and passive heating and cooling. Tokyo may be better than a lot of Asian cities, partly because it developed several decades earlier, but compared to cities like Portland in the United States, Vancouver in Canada, Copenhagen in Denmark, or Stockholm in Sweden, which have made tremendous strides in urban greening and shifting to renewable energy, it has a long way to go.”

This said, Brown notes, it excels in certain departments. “Public transportation, for example, is fabulous, especially when compared to the United States, where cars continue to dominate. Compared to the 1970s, air pollution from automobiles and factories has much decreased, and public transportation has been hugely beneficial in this respect.”

Rethinking Rivers and Canals

One thing that Brown laments regarding life in contemporary Tokyo is the decreasing appreciation that the local authorities have shown for the city’s waterways. “For hundreds of years the extended network of rivers and canals in Edo, and then Tokyo, was used as a transportation system,” he says. “But after the Meiji period [1868–1912], they were gradually replaced first by railroads and then by road transportation until people forgot how important they were. This is a pity because during the Edo period [1603–1868] there was a more symbiotic relationship with rivers and the sea. In the past, for example, they were an important resource for the fishing industry, so people tried not to pollute them.

“Reestablishing more comprehensive urban water transportation networks, as opposed to having just a few boats for tourists, is only a part of the overall rethinking of urban transport that is necessary now. Ideally, the use of the individual automobile should be suppressed, and our cities should be made navigable by a combination of buses, light rail, bicycles, and pedestrian-friendly areas.

“Luckily, there is now a new awareness that Japanese cities would be more livable if they took better care of the waterways. Take Nihonbashi in Tokyo. This bridge was covered over with a highway in preparation for the 1964 Olympics. Luckily, they are now burying that particular stretch of the highway, with plans to open up the river and make it usable again. Something similar was done in Seoul over a decade ago, and was very successful.”

The portion of the Shuto Expressway covering the river where the famed bridge Nihonbashi stands in Chūō, Tokyo. (© Jiji)

Wiser Uses of Waste Material

Another issue that is related to water management is how cities treat waste. Tokyo produces a lot of it, and its huge impact is felt in many areas. Granted, a lot of waste is being recycled now, but ultimately, almost everything is either incinerated or used for landfill. Tokyo Bay, for instance, has been gradually filled with artificial islands constructed partly from this waste.”

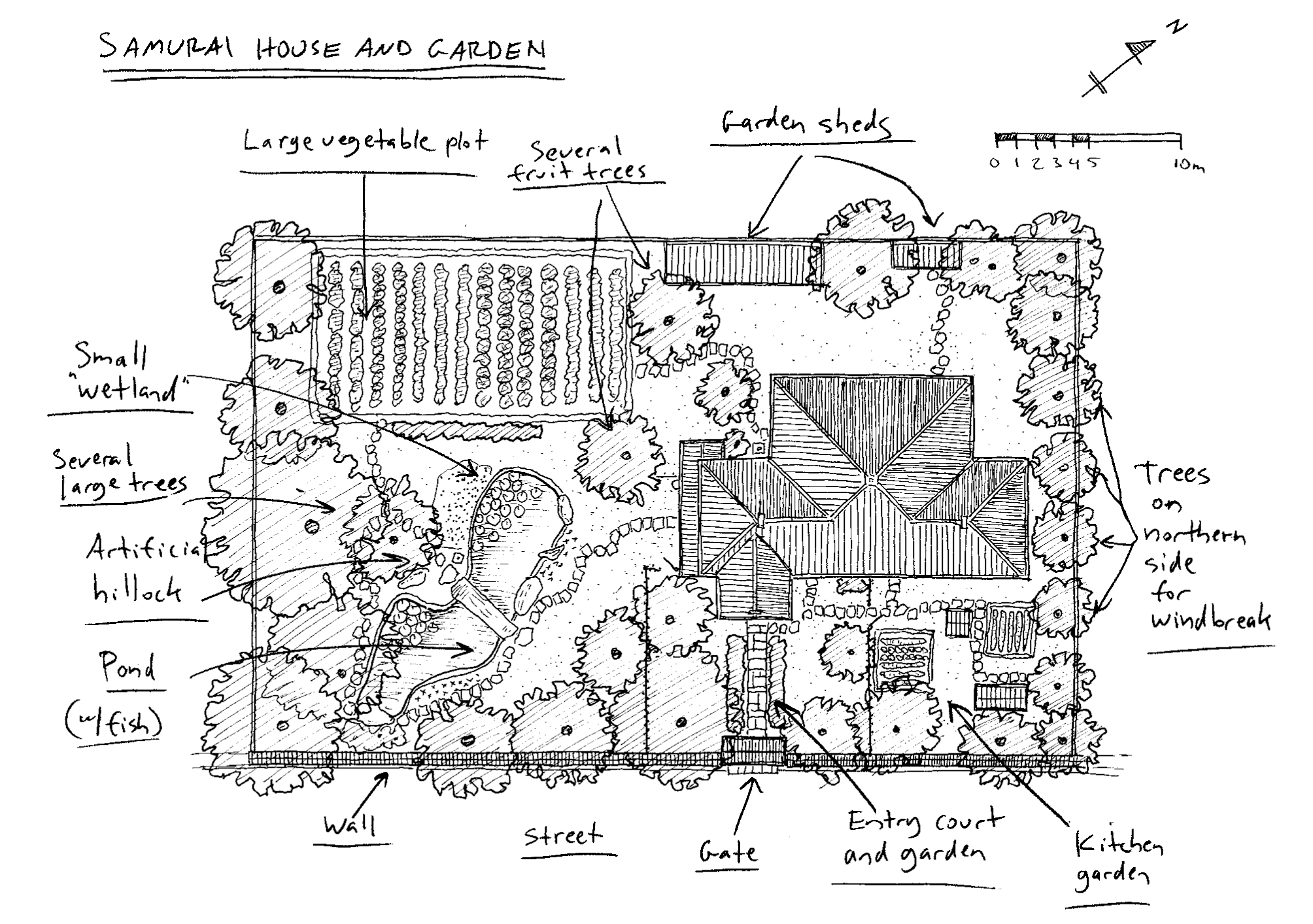

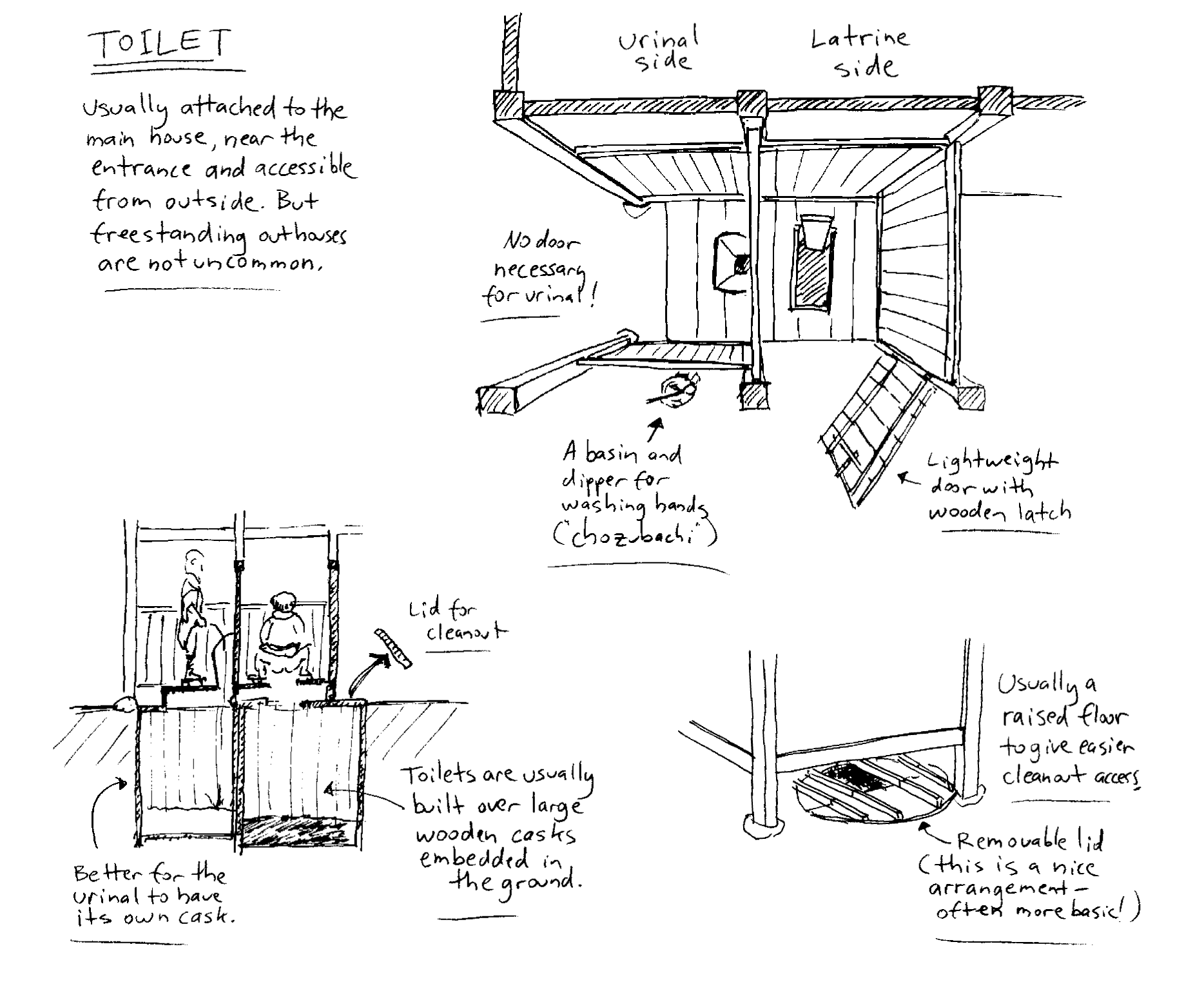

Other forms of waste come into the picture as well. “In the Edo period, human waste was recycled into the agricultural process as fertilizer,” Brown says. “At that time, in Europe and North America, there were terrible outbreaks of cholera and other diseases because human waste ended up in the rivers. But Edo avoided that by constantly cleaning out the toilets and bringing the waste to the farms. They kept doing that well into the nineteenth century.

“Now we use flushing toilets. They are clean and safe, but the problem with this system is that we end up putting the waste into the rivers and the water supply, so then it requires great treatment plants with chemicals to make that water drinkable again. When you think about the Edo period, they did it brilliantly by using that waste as fertilizer. They had better food production while preventing diseases. It was much more hygienic and they didn’t pollute the water supply. It was said that you could take water from the Sumida River and make tea with it. Maybe you didn’t want to drink it as it was, but you could boil and ingest it.”

While it is true that resuming the old practice may be difficult, the fact is that tremendous strides have been made worldwide in developing practical systems for waste processing that can help to reclaim and reuse human waste rather than flushing it away.

Dialing Down the Heat

Battling the summer heat is another case in which modern technology has made the problem worse. In the hot and humid summer months, most Japanese cities are subjected to what is called the “heat island effect” because the building surfaces and the roads retain and reflect heat. “It’s just that cities are not built to take advantage of natural cooling,” Brown says. “Our air conditioning is going full blast, and this is a big problem.”

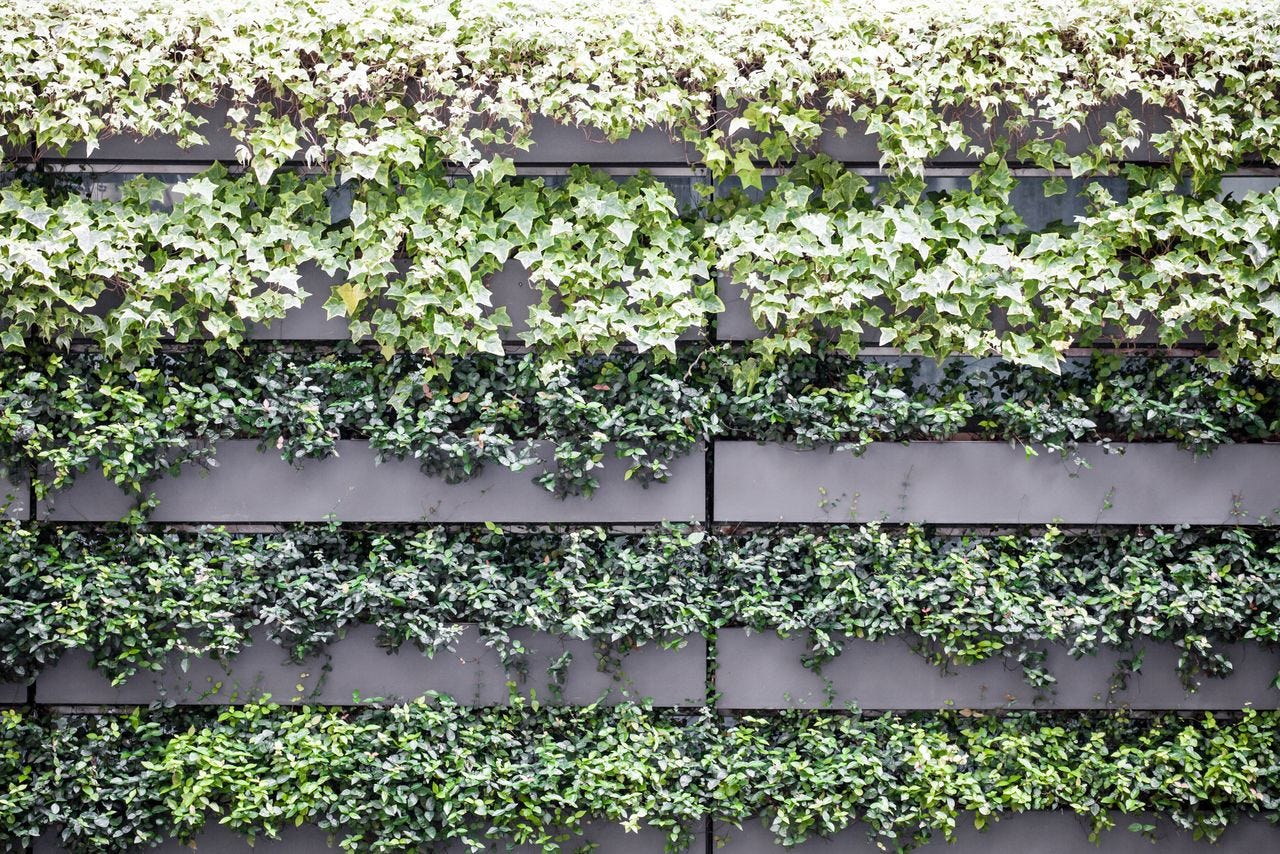

Even in this case, the people of Edo had found a simple and eco-friendly solution. “They used lightweight, removable trellises covered with climbing vines to help shade the interiors of their homes,” Brown says. “Like ‘green curtains,’ they were often a source of food, like beans and squash—or of color, like morning glories—as well as shade. I think the houses in the Edo period were probably more comfortable, even without using power, than our current houses are now.”

A modern form of a “green curtain” built on the side of a structure to enhance its cooling in summer. (© Pixta)

Recently, notes Brown, the “green curtain” idea has found renewed acceptance and has been adapted for use on institutional buildings. One large corporation has added green curtain to five factories, using morning glories and edible bitter gourd plants called gōya to make living shade curtains over 140 meters in length. The firm has found that the added shade greatly reduced the need for air-conditioning in the factories, particularly in the morning. Other groups have begun similar projects to add green curtains to schools and government buildings across the country. This idea is excellent, inexpensive, easy to do, and rooted in tradition.”

Old Ideas for New Thinking

While technology offers solutions, Brown is more interested in changing people’s minds. “I would like people to adopt a more restorative approach to whatever they do,” he says. “In other words, we should aim at implementing the sort of circular economy where most things are recycled and put back to use. We should have a more symbiotic relationship with the environment.”

Brown is conscious that changing people’s habits is the most difficult hurdle to clear. “Let’s face it, we humans are creatures of habit, and we get used to convenience,” he says. “A lot of what we do that is environmentally damaging or unsound has to do with that, and it’s hard to give up our comforts. But I try to encourage people at least to think a little bit, when they are purchasing or using something, whether it’s food or clothing or appliances—to think about where all those resources come from, how they get to us, and then where they end up.”

In the end, Brown thinks that city planning should be like gardening. “Rather than building monstrously overscaled towers for wealthy people and destroying neighborhoods that were functioning beautifully, we could learn from how Edo preserved its natural environment by providing habitats for many species while beautifully meeting the needs of residents,” he says. Cities planned in this way, like Edo was, can still support a large population and its complex economic activity and transportation systems because they are carefully integrated into their local ecosystems. The key lies in understanding how human habitation and natural systems form an interdependent, functioning whole.