Do you remember when film shows were divided in two halves? There was a break between them, and the theater staff walked around selling food and drinks.

Well, the second half of this story is about to begin, so hurry up to your seat! And if you missed the first part, you can read it here. Are you comfortable? Okay, let’s start.

A visit to the Motomiya Eiga Gekijo truly feels like travelling with a time machine back to the Showa period (1926-1989) when cinema-going was both a common and magical experience. In the dimly lit lobby, next to cuttings of interviews and articles about the theater and its owner, there are photos of silver screen stars such as Kitaoji Kin’ya and Kobayashi Akira, as well as posters of Showa-era movies. It is here that Tamura Shuji spends many days during the warmer season, sitting on a chair near the entrance.

The retro feeling and nostalgic atmosphere even pervade the parterre. The exposed concrete floor looks rough, but the 100 wooden chairs are surprisingly comfortable to sit on and the zabuton (traditional cushions) add a nice, homely touch. These are also the only seats available: after the two upper floors were damaged by the earthquake, the gallery area was walled up and is now closed off to the public.

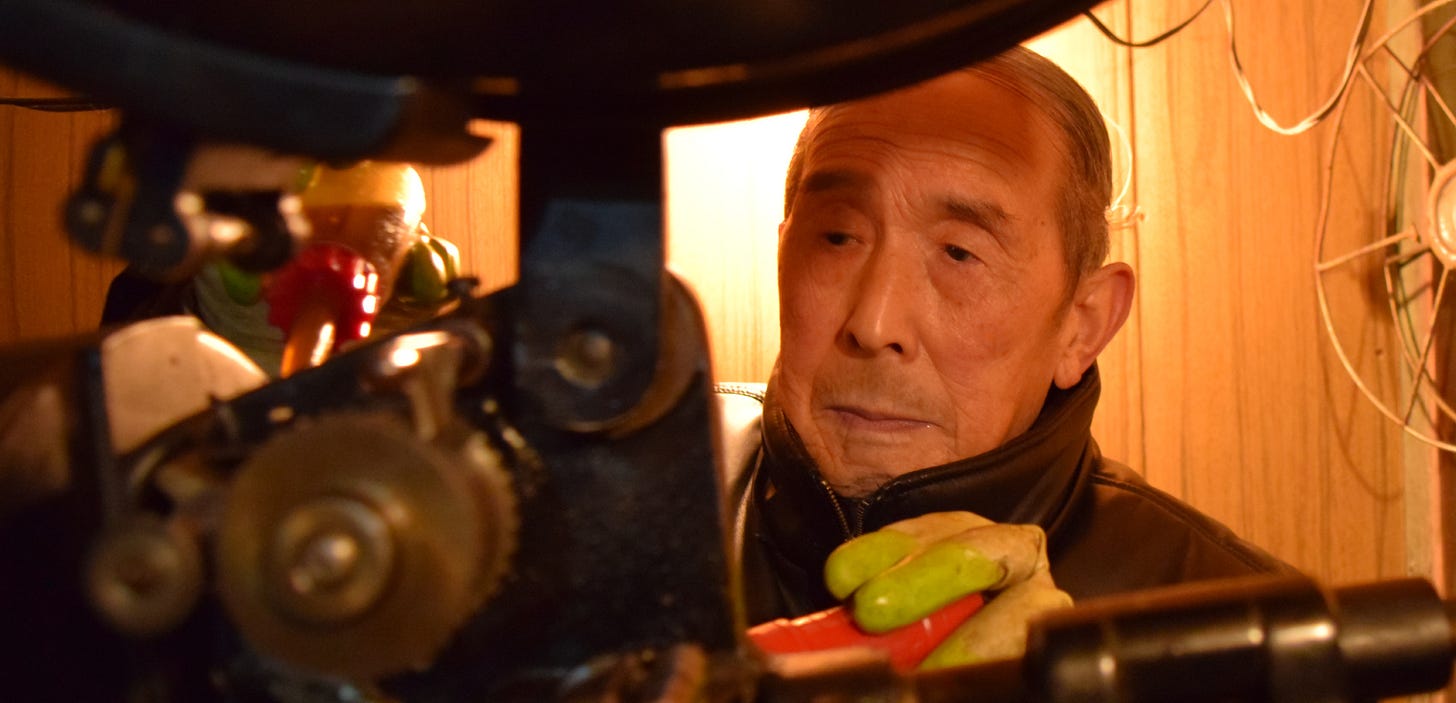

In a sense, the most surprising place inside the theater is the projection room. It is here that a real relic can be admired: a carbon-type projector made in 1957. Shuji says that this is the only place in the prefecture where such a projector can be found, but one would probably have a hard time finding a similar model anywhere else in Japan. Most people have no idea how it works anymore, so Tamura-san patiently explains how he conjures up moving images from this ancient machine.

“Instead of a xenon arc lamp, which is the most common light source today, this projector uses carbon rods as electrodes,” he says. “To be more precise, there are two types of carbon rods: “plus rods” and “minus rods.” When the plus and minus are brought close together, electricity will flow and the projector uses the light emitted at that time. As the rods burn, they shorten little by little like a candle.

“However, there is a drawback to this system: we constantly have to make sure that the right distance between the rods is maintained. In other words, they neither can be too close together nor too far apart. It is the job of the projectionist to finely adjust the distance between them.”

According to Tamura, another problem with this kind of machine is that since the electrodes are not enclosed in a glass bulb like a xenon lamp, the projector generates a lot of heat and during the screening, the area around the projector becomes very hot. “Not only it gets pretty hot in the projection room, so one sweats a lot in summer,” he says, “but the projectionist must be careful that it does not catch fire. This was particularly dangerous in the past, with old films that used flammable celluloid.”

In 1984, a fire broke out at the National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, destroying many valuable celluloid movie films that had been stored there. Luckily, the industry transitioned to cellulose acetate film (also called “safety film”) in the mid-1950s, and later to polyester film stock, while now many theaters use digital projectors. “People come from all around Japan to experience a film shown on an old projector," Shuji says. “It may be not as beautiful as digital, but the warm feeling you get from it is rather unique.”

Currently, the Motomiya Eiga Gekijo is managed jointly by Shuji and his daughter Yuko who usually lives in Tokyo and works at a “mini theater” (a small independent cinema). Screenings are held several times a year including hosting group trips. The theater is also used as an event and concert venue, and filming location. “People visit very often, even when the theater is closed, just to have a look,” Shuji says. “I'm happy that they want to see a place that has been empty for such a long time. After all, movies are my purpose in life. But I never thought I would be in the limelight at my age” (laughs).

The Tamuras often screen compilations made by Shuji by editing and choosing the good scenes from the films he has on hand. “I want to create interesting shows that will please the audience by leaving out the boring bits,” he says. “It's like the last scene in New Cinema Paradise. I want to show movies that will remain in people’s memories.”

“Also, in November 2021, we organized a tour program around the old movie theaters (e.g. Asahiza, Shintomiza) that still survive in Fukushima,” Yuko says, “and we had an opportunity to show again Police Diary, the film that still holds Motomiya’s box office record, 66 years after the original screening. It was a memorable event for us.”

Though the theater is only open for a few days every year, Shuji is careful to do maintenance as often as possible, so they can screen at any time. “Preparation time is the same for a two-minute short or a two-hour film,” he says. “You see, it's not impossible to show the movie right away. I have to check the film, check the condition of the projector, clean the venue... I want to take good care of the customers. If those things are neglected, it is easy for the film to be ruined or for accidents to occur.”

All over Japan, old movie theaters are closing one after another and it is very difficult for a cinema to take up a whole building like in the past. Now most theaters have become tenants. “A lot of people seem to agree that it’s nearly impossible to make a living in this business," Yuko says, “yet new movies continue to be made. I even get phone calls from filmmakers asking me to screen their own work. Other people visit while scouting for locations and when they step into the theater, you can see how excited they get. Also, some time ago, a local man in his 60s brought the DVD of a monster movie that he had missed when it had been released and watched it on the screen. Rental movie theaters… isn't that a great idea?”

The 2019 typhoon, flood damage, and the subsequent COVID-19 pandemic have scarred the region and people have left town. Familiar mom-and-pop shops and candy stores have disappeared. This is the sad reality. But the Tamuras are not done yet. “The Motomiya Eiga Gekijo is still alive and well because people keep coming,” Shuji says, “and I will protect this theater for as long as movies are made.”

If you don’t know New Cinema Paradise’s last scene mentioned by Tamura-san, and even if you already know it, here it is. Don’t miss it!

Fantastic post and the link to the last scene of Nuovo Cinema Paradiso was perfect here.

The follow up comes through! Wonderful read.