A few weeks ago I read this sad, shocking news on the internet:

After more than 50 years, Iwanami Hall in Kanda-Jinbocho is screening its very last film on July 29 due to the impact of the pandemic. This mini-cinema is a favorite haunt of Tokyoites who love indie films that you just won’t find at bigger multiplexes. The theatre is still screening movies until its last day, so head to Jinbocho to catch foreign films like Ankon and Golden Thread while you still can.

First opened in 1968, Iwanami Hall spearheaded the rise of so-called mini-theaters: independent movie theaters characterized by a smaller size and seating capacity (typically 200 people of less) in comparison to larger cinemas. The mini theater movement gained popularity in the 1970s and particularly in the ‘80s thanks to a novel curatorial approach that favored films with social themes that were once considered inappropriate for film distribution as well as works from unknown female directors. While some focused on foreign art-house films, others took the lead in releasing cutting-edge films by little-known Japanese filmmakers thus triggering the revival of quality domestic film production.

The Iwanami Jinbocho Building housing the movie theater

Iwanami Hall was born as a multipurpose hall built by Iwanami Shoten, one of Japan’s biggest publishing companies, and for many years its cutting-edge program was curated by two women: Takano Etsuko and Kawakita Kashiko.

Takano was Iwanami Hall’s general manager. “Madame Kawakita,” as she was popularly known abroad, had pioneered the import of foreign films to Japan through Towa Shōji, a small company she had founded with her husband. Later she formed Nihon Ārto Shiata Undō no Kai (Japan Art Theatre Movement Party) with the aim of establishing theaters that would show art films.

In 1974, the two women launched a new film distribution project called Equipe de Cinema, turned Iwanami Hall into a theater and started showcasing foreign films from little-known countries. In the second issue of their newsletter, Equipe de Cinema (1974), they stated that “Our primary mission is to uncover hidden masterpieces and show them to the public, and to put a spotlight on film countries, and specifically new and powerful directors from the third world.”

Personally, I sometimes found that they were trying a little too hard. They seemed to rejoice in discovering austere, minimalist titles from Bulgaria, Chile and Cyprus that had a soporific effect on the 60- and 70-year-olds who made up their regular audience. After a while, heads started dangling and swaying, and you could even hear the occasional snoring.

Iwanami Hall’s humble, unobtrusive entrance

In many respects, Tokyo is a moviegoer paradise. There are more than 60 theaters only in central Tokyo, almost half of them concentrated in Shibuya and the Ginza-Yurakucho area.

Even content-wise, movie buffs can easily find something they like, whatever they like: from Hollywood blockbusters to unknown indie art films, from anime to documentaries, almost every week there is something for everyone. Indeed, there was a time, when I worked in central Tokyo, that I had some free time in the afternoon and I would go to the movies at least once a week.

Architecturally speaking, Cinema Rise was probably my favorite. Located on top of Supein-zaka (Spain Slope) in Shibuya, it was a mix of dungeon and bunker. It opened in 1986 and quickly became a magnet for hip movie fans.

The place’s dark atmosphere and reinforced concrete structure was offset by cute shocking pink toilets.

On the other end of the Shibuya art-film scene stood Uplink Factory: two small screens, wood flooring and a bunch of assorted chairs scattered around a cozy room. It closed down last year, yet another victim of the pandemic. Luckily, two more Uplink theaters are still open, one in Tokyo’s western suburbs and another one in Kyoto.

Born in 1995, Cine Amuse was one of the latest addition to the movie-going scene.

Cine Amuse East had a frightening, screaming-red interior; Cine Amuse West was a warm, deep blue. They had a kickass program.

They hit the first pages of the local press when they showed Yasukuni, Chinese director Li Ying’s documentary on the controversial shrine where more than 2 million of Japan's war dead are enshrined, including more than 1,000 including 14 Class-A war criminals.

A police car was stationed in front of the theater the whole time the film was screened because right-winger groups were threatening to burn down the place.

Alas, Cine amuse closed in 2009.

One of the things I love most about Japanese theaters are the racks full of movie flyers that distributors print to advertise upcoming films. They are colorful, beautifully printed things full of pictures. I must have more than 500 in my collection.

Many people say that Tokyo is an expensive city. However, the great thing about Tokyo is that whatever you are into (eating out, clothes, entertainment) you can always find cheaper options, and movies are no exception. If you want to catch a new release, you have to pay for the privilege: 1,800-1,900 yen a pop (a few hundred yen cheaper for an advance ticket).

Yet there’s a way to get around this obstacle as Tokyo is home to a few cinemas specializing in reruns. Not only you can watch two films for the price of one ticket, most of them have a point card system or give you a discount voucher you can use the next time you pay them a visit.

Years ago, these places were everywhere. Alas, they have recently become an endangered species. Which is a pity because each one of them has (or I should say “had”) a distinct atmosphere and attracts a completely different set of people, which makes them ideal places to do some “anthropological research.” Here are some of my favorites.

Until a few years ago, the bowels of the JR Yamanote train line were not only home to yakitori stalls and endless bars and restaurants. Two of the more characteristic Tokyo theaters shared the same box-office under the Shinbashi Station tracks.

If you were wondering where the Japanese economy was heading, you only had to take the door on the left and step inside the Bunka Gekijo (Culture Theater) to discover scores of worn-out middle-aged salarimen snoring through a couple of action movies (the specialty of the house).

The enjoyment of these contemporary grindhouse flicks was regularly disrupted by the noise of the trains running upstairs and the people going to the toilets (strategically placed on both sides of the screen). Although nobody seemed to notice, and anyway 700 yen was the cheapest you would pay in Tokyo for a double bill.

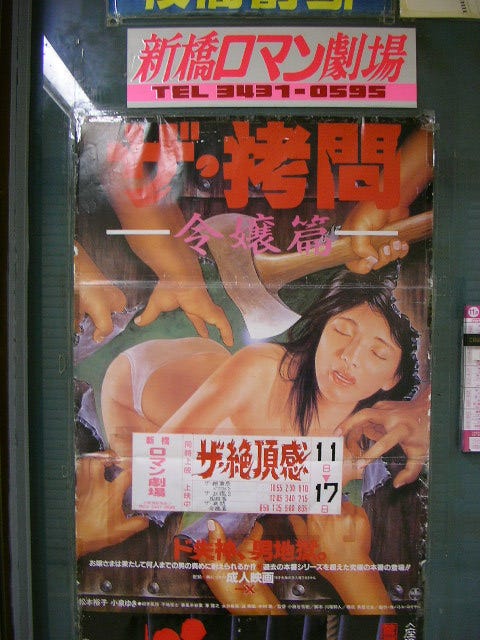

If you dug mildly naughtier pleasures, you took the door on the right of the box office and got into the Roman Gekijo (Roman Theater). For 1,000 yen you could while your time away with a couple of classics from the vast Roman Porno tradition of Japanese softcore flicks.

On the other end of the cinematic spectrum, the still surviving Ginrei Hall appeals to the more refined tastes of forty- and fifty-something women who like to dine in nearby restaurant-famous Kagurazaka.

Its eclectic menu of tasteful dramas, love stories, and assorted tearjerkers guarantees that on any given day 90% of the audience is comprised of women – plus a few elderly gentlemen.

Not to be missed is the underground restroom; a classic job with swinging doors and tiled walls, probably built 50 years ago.

http://www.ginreihall.com

Back to nostalgia mode, when I felt particularly lazy I would head to a couple of cinemas that were located on my same train line: Sangenjaya Cinema and Sangenjaya Chuo Gekijo.

These two theaters shared the same backstreet and showed the same kind of mainstream movies. They battled for years for cinematic supremacy in the area until they both folded.

The bigger and somewhat grander Chuo Gekijo (Central Theater) sported a weirdly cute couple of demon-like nude figures above the main entrance, while the screen was guarded by heavy dark red curtains strategically lighted for maximum effect.

Once inside, one breathed the worn-out, slightly dilapidated atmosphere of glories past that was typical of many such theaters. The seats were some of the most uncomfortable you would find in Tokyo, and it got rather cold in winter – which, some would say, added another touch of originality to the place.

Sangenjaya Cinema, on the other side, was so unassuming that if it wasn’t for the many posters and flyers advertising the upcoming shows, one could walk past it without even noticing its presence.

Inside, a sagging leather sofa sat in the middle of the tiny waiting area. For some reason, few people dare to sit on it, probably worried that it could crack under their weight.

Even the seats in front of the screen looked way past their prime, but they were actually very comfortable. People waited between shows while munching on something, listening to the ever-present jazz music and staring at the mustard-colored curtains.

The view from Sangenjaya Cinema’s toilet window. The smokestack belonged to a public bath now long gone.

Among the still surviving double-bill places is Shin Bungeiza. For hardcore aficionados of classic and minor Japanese masterpieces, few places beat this theater strategically located smack in the middle of the Ikebukuro red-light district.

Do not worry, though, because the third floor of this dilapidated-looking building houses a clean, well-lit theater with plenty of space which attracts a fairly eclectic clientele.

Shin Bungeiza shows new and old western films as well, but its main draw are the series it regularly devotes to both famous and marginal Japanese directors and actors from the past.

Another distinctive feature of this theater are its three-bill all-night programs which usually last between 22:30 and 6:00 and explore the deeper reaches of 1950s Japanese Science Fiction and 1970s Italian horror and Eurotrash cinema.

http://www.shin-bungeiza.com/

Yet another survivor is Meguro Cinema. The best feature of this underground place is the small but interesting library of film-related books and magazines one can peruse while waiting for the next show. When I was young and wild (ha!) I tried - and failed - more than once to steal a nice history of cinema.

But the best mini theater of all was the ATG Theater. It was so small that instead of the usual seats there was just a free-for-all carpeted area, and you were required to remove your shoes at the entrance. This is the place where, on a freezing-cold afternoon, I saw John Cassavetes’s Shadows for the first time.

Ironically, I never got to take pictures of that place. All those memories are now inside my head and in the deep of my heart. Those were the days, of being young and (mildly) wild and cluelessly romantic. Cheers!

“What’s your favorite movie?” is a rather dumb question. I mean, there are so many I would personally find it hard to name just one. But what is one (or two, or five) of your favorite films? Please share in the comments.

Such an interesting read, Gianni. The movie flyers sound beautiful, nice that you’ve collected so many. As for favorite movies: The Godfather, parts 1 & 2.

"The Last Picture Show" has been one of my long-time faves so it's interesting (and quite fitting) to see you using that as a title for your post. Thanks for sharing your story.