The city is a vast, dense sea of electrical energy fields and waves estimated to be 100 million times stronger than 100 years ago. (…) The accumulative cocktail of magnetic and electrical fields generated by power transmission lines, pylons and masts, mobile phones, computers, television and radio, lighting, wiring, and household appliances can seriously interfere with the subtle natural balances of each cell in our body. These massive currents crisscrossing the urban environment are unseen, unfelt, unheard, without taste or smell, yet they operate upon us, albeit at a subconscious level.

(Charles Landry, The Art of City-Making, 2006)

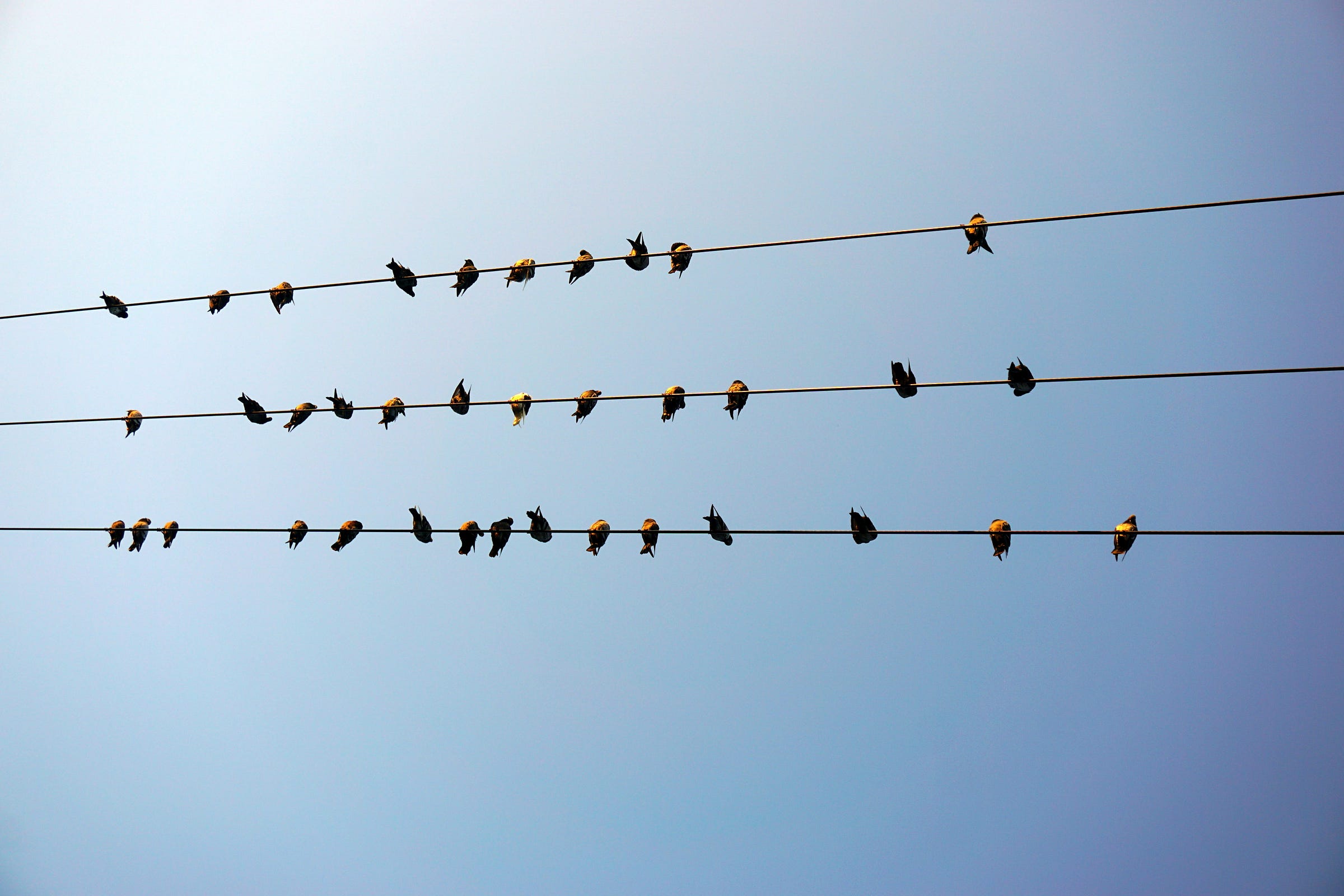

Japanese cities are covered in a thick web and my neighborhood is no exception.

It feels like giant spiders have turned the whole of Japan into their hunting grounds.

In truth, they are just electric wires. Lots of them.

I say “just” but they are everywhere. They are an unavoidable, inescapable presence. I’m sure most people here don’t even notice them; they just take them for granted. But where I was born, all wires are laid underground.

I have a rather complicated relationship with overhead wires and the totem poles that come with them. The first time I came to Japan I found them strangely fascinating, probably because I could only see intersecting lines. At the time, I was into abstract painting (Piet Mondrian was one of my favorite artists) so I guess I translated the chaos overhead into graphics.

Then I moved to Japan, and after a while I had to face the stark reality of their ugliness. They can be a pretty overwhelming presence. Almost threatening, if you are caught in a bad mood.

After all, not long ago, many observers were worried by telegraph, telephone and electric wires. As John R. Stilgoe writes in Outside Lies Magic, they feared that those wires, like “a great net strung over their heads, snatched ideas and dreams and independence.”

And the poor housewives, at the turn of the century, worried that electricity leaked from any outlet lacking a plugged-in lamp, causing headaches and cancer.

By the way, the first telegraph poles appeared in Japan in 1869 when the telegraph service began between Tokyo and Yokohama.

The first electric poles, of course, were made of wood. Japan's first concrete utility poles, on the other hand, were erected in Hakodate (Hokkaido) in 1923, and unlike the general cylindrical variety, they were square-shaped.

The endless lines of gray concrete poles, all slightly out of perpendicular, marching along every street, add to the feeling of impending doom.

They come equipped with transformers - the cylindrical fruit of the electric tree - either pumping electricity up to race farther along the line or pumping it down every few houses.

As of the end of 2018, there were 35.92 million utility poles in Japan, of which about two-thirds, or about 22.01 million, were owned by general power transmission and distribution companies.

And those housewives from the good ole days were not completely wrong. Indeed, live wires leak. I scrutinized a utility pole near my house and found a thick wire leading down the pole to an even thicker rod pounded into the earth. These wires help keep transformers from exploding, dominolike, during lightning strikes.

I’ve always been curious about the seemingly wild jungle in my neighborhood, all those wires of different thickness dangling over our heads. At last, yesterday I struck gold: a maintenance team visited my street and I immediately set to bother them with some inane questions. I guess that being approached by a nosy foreigner caught them off balance, but instead of telling me to go to hell, they were very kind and almost seemed glad that someone was interested in their work.

I learned that the higher placed, thinner wires are the high-tension lines. They are old, so they are still made of copper. Nothing tall, nothing that might fall across, stand near them, and nothing that might reach up stands beneath them. Nothing must grow tall enough to carry some storm-induced spark to the ground.

The lower, thicker lines are the communication cables (telephone lines, optical communication cables, cable TV coaxial cables, etc.). They are newer and made of aluminum.

I was also surprised to learn that concrete poles are hollow structures that use steel bars for the framework. These pillars are designed not to be destroyed by a lateral bending strength of approximately 1.2 tons.

In case you want to put one of those things in your garden, they are not particularly expensive: the price for an eight-meter utility pole is about 45,000 yen.

Many (most?) countries, snake their cables underground in conduits, safe from lightning strikes, snowstorms, falling tree limbs and errant motorists.

Stilgoe goes as far as to say that “Real cities have underground wires, not lines strung atop wood poles.”

The rate of underground utility poles in central Tokyo is about 7%, while the undergrounding rate in Japan is about 2%. Does that mean that Tokyo is not a real city?

But why are there so few underground lines in Japan?

I found this interesting answer on Quora:

“First, there is cost. The costs involved in planting the lines and then redoing the connections to every building along the course is prohibitive. I have been given to understand that the underground option is several times more expensive. In addition to the financial costs there are considerable time costs as well. In putting lines underground, it is necessary to dig up the streets and this cause disruption to those who live there.

“Another reason has to do with maintenance and repair. One of the things they learned after the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995 was that underground lines are problematic after a big shake.”

I guess I can agree with that. On the other hand, if the pillars fall down because of an earthquake, they make the situation even worse. And anyway, other countries that are regularly visited by earthquakes have put all the electric lines underground.

Electric poles, by the way, are installed by burying about one-sixth of the total length in the ground. The distance between utility poles is generally said to be about 30 meters though, of course, it varies depending on the circumstances.

In the end, it mainly seems to be a matter of saving money. And to hell with the consequences.

So what do you think? Next time you find yourself walking a Japanese street, look up and tell me what you feel.

PS Photography can sometimes turn ugly or mundane things into something interesting, or even beautiful. This one was taken by Joel Pulliam, a Tokyo-based photographer. He publishes an interesting newsletter. Check it out.

Yes, they are not aesthetically-pleasing in my book, no matter how you dress it up, but I understand that underground wiring can be problematic, what with earthquakes and tremors, so the crisscrossing of the sky is a necessary evil.

Great post! I actually have always liked above-ground utilities. But yeah that puts me at odds with neighbors in the past who griped that they weren't being "undergrounded" in our neighborhoods. I like looking at them though. Kind of like cell phone towers - where I used to live in Arizona, they would disguise them as cactus, palm trees, or pine trees, and they looked ridiculous. Just leave them as is, I say.