Dear readers, the following story is from a Japan-related Substack I’ve just discovered. According to the author, Jesper Koll, Japan is in a demographic sweet spot that empowers the young and forces real change in corporate culture. More specifically, one of the key forces in current Japanese society is scarcity of labor because it forces a fundamental re-think of how the most important asset for innovation and prosperity - human capital - is deployed.

I don’t know if Mr. Koll is right, but I certainly hope so, as this would mean better salaries, better working conditions, and better work/life balance.

Please read on.

Japan’s new golden generation

The current generation of Japanese high school and university graduates can look forward to achieving something that, unfortunately, looks increasingly unlikely for their peers in the US, Germany, France, UK, South Korea or other advanced industrial economies. Japan will become the envy of the world because it is the one country where the next generation is poised to be better off economically than its parents. Japan is in a demographic sweet spot.

The reason for my optimism is simple. It is Japan’s demographic destiny combined with the basic forces of economics — demand and supply. As the supply of labor goes down, the price of labor (wages and income) will go up. Contrary to the simple-minded arguments of the demographic doomsday brigade, rising wages and better incomes actually do trigger a positive supply response.

People who previously had given up on looking for work all of a sudden become attracted by better pay and better-quality employment contracts. They start working again, and so do people who, quite rationally, had decided that they were better off living off their parents or grandparents rather than working for what they deemed subpar compensation or under unacceptable conditions. The magic of free markets actually does work in Japan.

Employment is outrunning population decline

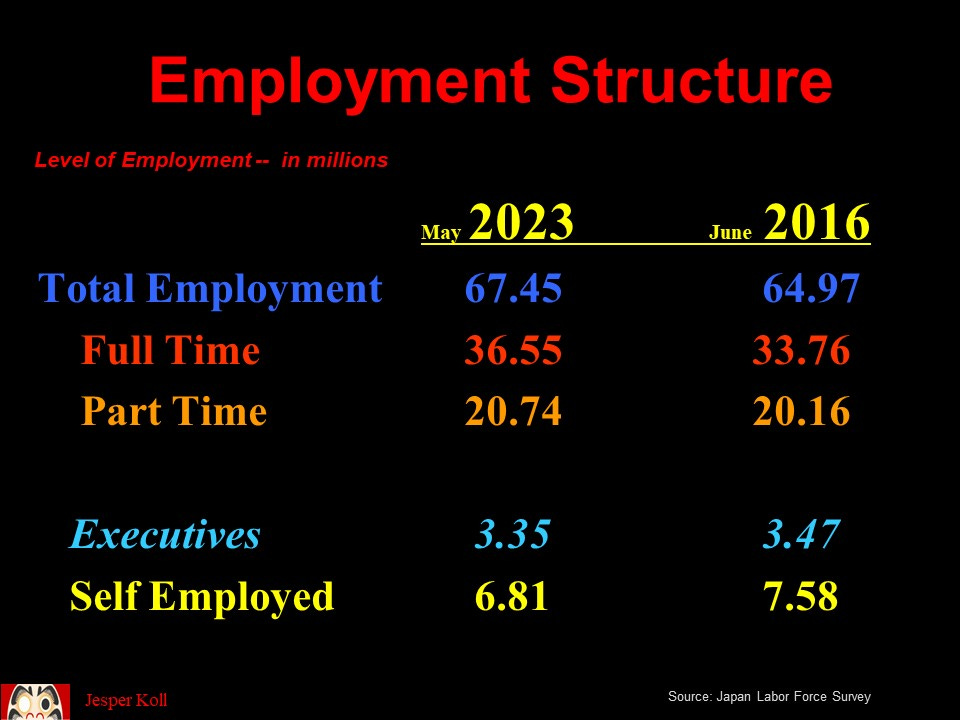

Just look at the numbers. In the past six years, June 2016 to May 2023 (which at the time of writing was the latest monthly data available), Japan’s total employment rose by 2.48m people — from 64.97m to 67.45m. At the same time, Japan’s total population declined by approximately 3.6m to just above 123m. Importantly, in terms of percentage change, new job creation is running ahead of population decline: population down 2.5%, employment up 3.8% (mid-2016 to mid-2023).

The fact that most economists and commentators focus on death rather than employment tells you more about the dismal state of modern-day public discourse than it does about the true state of Japan’s economy. Jobs equals income equals purchasing power equals national income equals economic life, while death is, well, exactly that.

Importantly, Japan’s demographic doomsday brigade forgets that an economy is so much more than population arithmetic. How many people will look for work, will want to be employed or will become entrepreneurs and create new jobs for fellow citizens depends on many other factors than the simplistic ‘number of people aged 15 to 65’ (which is the standard definition of the potential labor force). Pay is one factor determining how willing somebody will be to forego a life of leisure. In rich countries like Japan, an even more important one is quality of job — possibilities of career advancement, work-life balance, stimulating team members, corporate culture and management flexibility.

Employees are in the driving seat

There is no question that in Japan the balance of power is shifting away from employers to employees — the ‘war for talent’ is poised to get more and more intense. While the current generation of parents was lucky to get a job at all during the decades of post-bubble misery, the new generation of high school and university graduates can pick and choose. Even top-listed companies are having to step up their game to attract and retain the best and brightest.

In my view, the intensifying war for talent will do more to fundamentally change Japanese corporate culture than any other force. The 1990s was marked by a lost generation and corporate cost-cutting; the 21st century will see the rise of a new golden generation where corporate Japan will focus on investing in human capital.

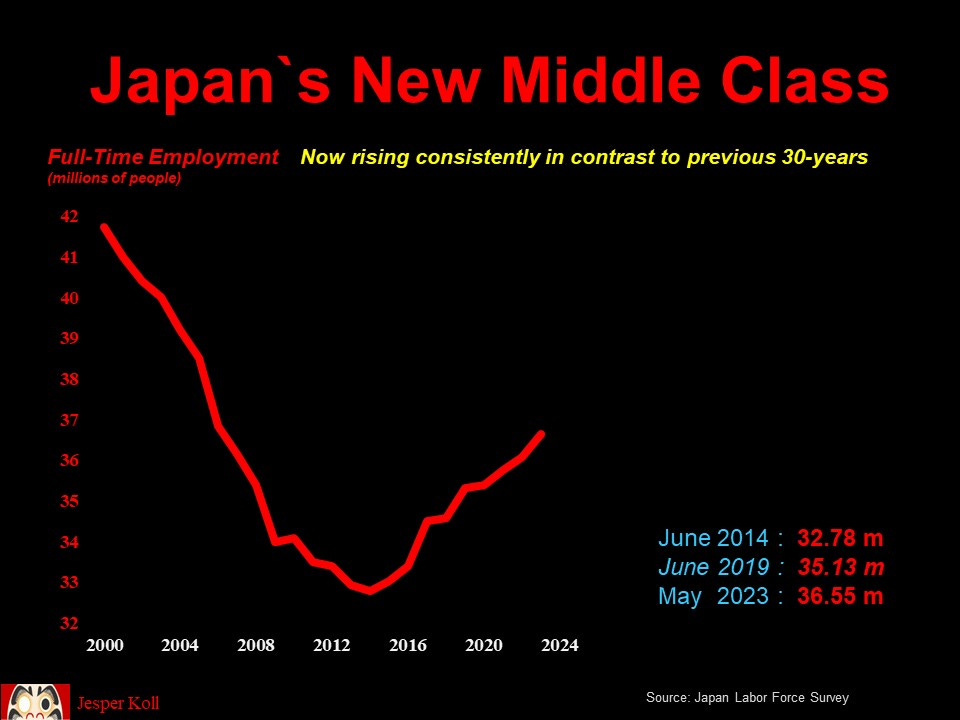

An important first sign of these positive structural dynamics is the fundamental improvement in the quality of jobs created. More and more jobs are being created on a full-time/regular employee basis. This is a reversal from a deeply entrenched trend that started with the labor reforms of 1995-96, which allowed non-regular employment across all industries.

Since 1996, the only net job creation was irregular employment, which surged from barely 20% of all employment to almost 40%. However, over the past years the growing scarcity of labor and intensifying war for talent has forced a positive inflection: from June 2019 to May 2023, full-time regular job creation rose by 1.24m, while part-time (irregular) employment fell by 740,000.

The fact that since the onslaught of the COVID crisis, corporate Japan has cut cheaper irregular workers while raising full-time employment is indicative of the deep-rooted structural change in Japan`s labor market and corporate hiring strategies.

Interestingly, this 1.24m figure for new full-time jobs created since mid-2019 stands out even more given that total employment was actually down by 20,000 people over the same period. This is because in addition to the 740,000 drop in part-time employment, the number of self-employed is down 430,000, i.e. COVID commanded a severe toll on mom-and-pop shops; and, at the other end of the employment spectrum, the number of corporate executives is also down by 90,000.

These details deserve closer attention elsewhere – the ruling LDP, for example, has a structural popularity problem partly because self-employed mom-and-pop shops have always been a key constituency, and now they are, well, dying out….; but these details must not distract from the new Japan mega-trend: full-time jobs are back.

Turning Japan’s demographic destiny into a positive force

The rise in the quality of jobs — full time, not part time, not irregular or uncertain ‘geek economy’ jobs — creates the beginning of a virtuous cycle: better job security, higher incomes (full-time jobs typically pay approximately 35% more because workers receive a semi-annual bonus which non-full-time employees do not get) and access to credit and mortgages (again, less available to part-timers).

On top of these straightforward economic benefits, the socio-psychological impact is significant. An employed person is a valued part of a corporate culture and actively engaged in a functioning and goal-orientated socio-economic community. Japan’s demographic destiny means the young generation is wanted and valued. The older generation will have no choice but to fight for their services. By the end of May this year, 98% of the university students poised to graduate next March had already secured a full-time job.

For corporate Japan a similar rise in prosperity and competitiveness is possible, but it requires a fundamental rethink of how human capital is employed, motivated and valued. Since the labor reform of 1995-96, Japanese corporate leaders focused on cost-cutting, cost-saving and cutting corners with the cheapest, most unskilled workers possible. They were disinvesting in human capital. Switching back towards true investment in human capital will not be easy, not just because labor is scarce but also because working with increasingly intelligent machines will require a radically new skill set for both employees and managers.

The biggest challenge will be a long-overdue shift away from seniority-based promotion and compensation towards merit-based career management. Interestingly, one of Japan’s most unionized companies, the telecom giant NTT, started to introduce a meritocratic promotion system earlier this year.

Fun fact: in the 1960s, it took less than 15-years for a new recruit at an elite Keidanren Fortune 50 company to make it to bucho, general manager, level. Now it takes more than 25-years. In my view, Japan`s youth today sense it has got the same bargaining power that their grandparents` generation had in the 1960/70s: then, as now, labor was in short supply. More so than just bargaining for more money, today’s youth want to be put in charge of meaningful projects and given real responsibilities as soon as possible. The 我慢 (gaman) and just-wait-it-out attitude that marked their parents’ generation is not for them – `Sayonara Salaryman`.

Combining scarce labor with new technology will force a radical rethink of all aspects of workflow, internal processes and rules — leading to a fundamental reform of Japanese corporate culture. Of course, for the current baby-boomer leaders this is all 大変 (taihen) and difficult; but hey, management was never meant to be easy.

Most importantly: don’t let the whining of corporate leaders in the face of new challenges distract you from the new emerging mega-trend: Japan is headed into a new golden age for its young generation.

A new middle class will rise; and yes, I do want to be re-born as a 23-year-old Japanese.

Original article :

It's wonderful to read some good news! Thank you for the interesting read, Gianni.

my daughter is four now, and we are leaving japan when she graduates from elementary school in 8 years and 3 months. She'll do jhs, hs and uni in america. very positive economic dynamics are on the table, juuuuuust in case she wants to come back to japan and start a company after uni.