Hi there, December is always a busy time of the year for me, what with writing the last articles of the season and preparing the university finals, but we still have time for a couple of chapters of the Beatles adventures in Japan. This time around we are going to cover the all important venue and security issues that caused endless headaches to the Japanese authorities.

Next year I’m going to make a big push to develop Tokyo Calling, and any help is welcome to spread the word about it. Onegai shimasu!

By the time the band flew to Japan, Beatlemania (that in Japan was translated as Biitoruzu kyojidai or “the age of the Beatles craze”) was in full swing.

A lot of fans wanted to see the Beatles live but rigid social rules posed limits on when and how teenagers could attend a concert. Many high school students (this was particularly true for girls), for instance, could only go if accompanied by an adult while in certain cities, the schools had strict rules about extracurricular activities and forbade students to attend.

Beatlemania in Japan was called Biitoruzu kyojidai or “the age of the Beatles craze”

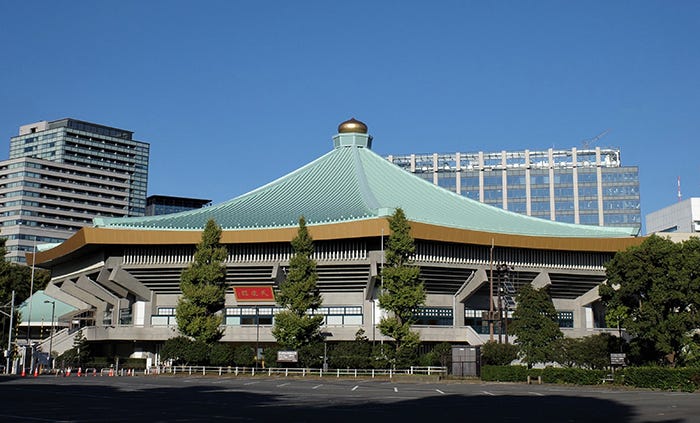

Finding a suitable and big enough venue was a source of endless problems. When Brian Epstein insisted that he wanted a place with at least 10,000 seats, the promoters thought they had found the ideal place in the Nippon Budokan, a brand-new indoor arena (it was built two years before for the Olympic Games) near the Imperial Palace with a capacity of more than 14,000. In the past, the Beatles had also played outdoors venues in America, Spain and Australia, but they were coming to Japan during the rainy season, so everybody agreed they needed a roof on their heads.

The problem with the Budokan was that the arena had been built to host martial arts competitions (its name translates as Martial Arts Hall) and as such it had acquired a semi-sacred status in the eyes of the conservatives and the famously litigious right-wingers. These groups had fought left-wingers and students in the streets throughout the 1950s and 60s and, most famously and shockingly, in October 1960, had assassinated the Socialist Party leader, Asanuma Inejiro, on live TV.

WARNING. Footage of the incident is age-restricted as Asanuma’s assassination (shown in slow motion) is rather graphic. If you want to see it, double click on the video below.

On a less glamorous but still worrying level, Shoriki Matsutaro, the chairman and owner of the Yomiuri Shinbun that was the main tour sponsor, had been stabbed and nearly killed by a right-winged extremist in 1934 when he had the audacity to organize a baseball game in Tokyo between a Japanese all-star squad and a team of American major leaguers. So he was well aware that any death threat had to be taken seriously.

Besides being the chair of the committee, back in 1961, to build the Budokan, Shoriki was a former police bureaucrat and judoist who had also served as the president of the country’s Atomic Energy Commission, so he was, ideologically speaking, not particularly favorable to the winds of cultural change.

However, economic considerations all too often trump ideology, and the Budokan administrators agreed that the money they would earn thanks to the four Mop Tops was a welcome revenue during a lull in their sports schedule.

Finally, on 26 May, the Yomiuri Shinbun announced that permission had been granted to the concerts (the short article was conveniently buried deep inside the newspaper).

As George Harrison later said in The Beatles Anthology TV documentary, “In Japan, people were demonstrating because the Budokan was supposed to be a special spiritual hall reserved for martial arts. So in the Budokan only violence and spirituality were approved of, not pop music.”

However, just two years later, when the Monkees performed at this very venue, almost nobody bothered to raise their voice in protest. Eventually, Harrison’s worries about the Budokan’s “violent legacy” were proven unfounded as the show biz’s economic interests proved stronger than traditional ideology and a seemingly endless parade of pop and rock artists made a point to play at the Budokan every time they visited Japan, resulting in such iconic live albums as Deep Purple’s Made in Japan (1972, also recorded at Osaka’s Festival Hall), Cheap Tricks at Budokan (1978) and Bob Dylan at Budokan (1979).

Among the many issues that were worrying the Japanese authorities, security was arguably the most pressing. The police, the fire department and the Budokan staff immediately started networking to coordinate their actions and try to cover all possible dangers and threats.

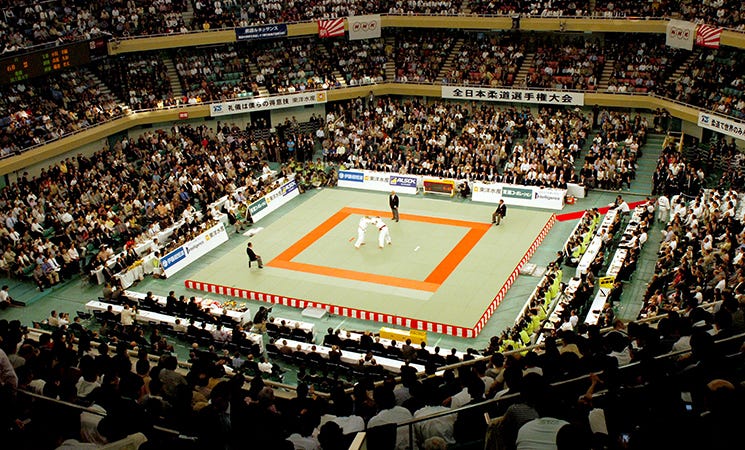

The police were so concerned that they viewed the event not as a concert but as an incident. Tokyo Metropolitan Police went so far as creating a special department, the “Special Security Headquarters,” that was divided into three sections: Haneda Airport, Hilton Hotel and Budokan. All in all, the number of police on duty during the five days the Beatles spent in Tokyo was 8,370 (a mix of district and local riot police, plainclothes and female officers). 3,000 of them were sent to Haneda, 2,000 guarded the hotel and 2,200 were deployed at the Budokan, including 350 officers who would stand in front of the stage.

8,370 cops were on duty during the Beatles’ stay in Tokyo

A lot of time was spent discussing how to ensure audience safety. Most of the attendees would sit on balcony seats and everybody was worried that some of them could become so emotional they would fall down. So they agreed to install a two-meter trellis to prevent falls from the second-floor balcony. Orders were also made not to put the light out at any time during the concert.

Most controversially (a typical case of how the Japanese can sometimes overdo things), security inside the Budokan was impossibly tight: for example, it was decided that the area right in front of the stage would not be used for seating, resulting in a spatial and emotional gaping hole between the musicians and their fans (and because nearly 3,000 front seats were made unavailable, the promoters lost a lot of money). Also, an electrified fence (!!!) was placed around the stage, so that in case of necessity, unruly fans could be shocked into submission. (To be continued)

Will the Japanese ever learn to relax? I mean the authorities and those in charge of running public places. Even today, things haven’t changed much: in most swimming pools and aquatic parks, for instance, everybody has to get out of the water every hour or so (or at least twice a day). The lifeguards will blow their whistles or a bell will ring signaling it’s time to get out. The five-minute break is meant - get this - for resting. It doesn’t matter if you are not tired or has just got there. After all, a rule is a rule is a rule.

So that’s it for today. Next week I’m going to post the final chapter of this story.

As usual, you can help by sharing this newsletter or a particular story on your social networks, or tell your friends how good Tokyo Calling is :-)

And don’t forget to subscribe!

This is so well-researched, Gianni - and so interesting to read!

All very interesting!