Dear readers, instead of my more-or-less weekly thank-you present for my paid subscribers, today I’m posting something different. Following my two recent posts about train-riding etiquette in Japan (you can find them here and here), I’m giving you a story by my friend, writer and collaborator, Baye McNeil.

Baye has his own very interesting and thought-provoking Substack that I urge you to check out, and a brand-new book he made with his lovely wife Miki. Please read on and let me know your thoughts.

The first writing I ever published on life in Japan was on my blog, Loco in Yokohama, in 2008. A post I titled “An empty seat on a crowded train.” And it caused quite a commotion, launching my blog into the blogosphere with a helluva bang.

If you’re a visibly non-Japanese (or even an un-traditional Japanese / mixed roots) person living here who rides mass transportation or goes out anywhere in public where ordinary Japanese people have the choice of sitting beside you or sitting elsewhere, then you’ve likely experienced the empty-seat phenomenon with varying frequency and intensity.

I had been living in Japan for four years before I wrote that post, and during those early years, the empty seat and I were consistent companions. So, I had plenty to say.

Our relationship, the seat and I, has undergone several phases in the intervening years. During this time, we’ve gotten to know one another very well. You could even say we’ve become intimate. And like with most intimate relationships, there comes the point where you’ve got to accept one another as is, warts and all, or call it quits.

Approaching the empty seat from this mindset helped me arrive at an idea that has sustained me through the most trying period of my tenure here. And that idea was this:

Before one can make peace with Japan, one must first make peace with the empty seat (in all its manifestations) and all that it signifies.

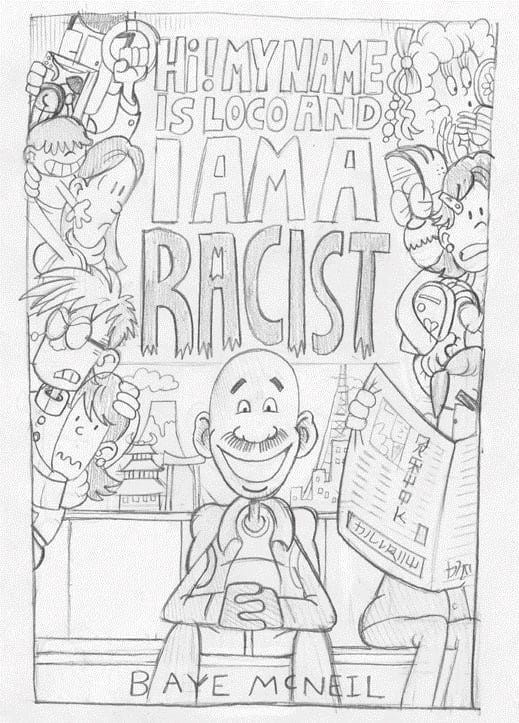

I conceived that idea on Oct. 16, 2008. Then I sat down and wrote that post. And that thesis — this desire to make peace with this infamous Japanese microaggression, and with what was going on inside me that made peace an imperative — became the driving force of what was to become one of the most talked-about blogs around these parts, as well as one of the most respected books on ex-pat life in Japan: Hi My Name is Loco and I am a Racist. (The cover art of that book illustrates the empty seat.)

Fast forward a little over a decade.

I was on the train taking full advantage of the extra space my fainthearted fellow commuters often allocate me. The car was full, but the seat beside mine was empty. I noticed it, of course, but on any given day, the attention I pay to it varies from too much to as little as possible. This was one of those as-little-as-possible days. I had my Smartphone out and was playing a Billiards game on it.

But life, as it has a habit of doing, intervened.

I looked up to see that the train had pulled into Jiyugaoka Station. The person sitting on the opposite side of the empty seat beside me got up, collected himself, and got off the train, along with a sizable number of the other passengers.

As the boarding passengers filed in, I told myself not to pay them any mind. I'm not too fond of that spat-on feeling I get when I see Japanese people, clearly eager to sit down, spot the empty seat near me, make an instinctual move toward it, and then, once their eyes have spotted me, abruptly alter their trajectory and scurry away.

I closed my eyes, nodded toward my iPhone, and re-opened them. I took a deep breath, and before I could exhale, I noticed two tiny legs standing before me. I looked up to see a mother and daughter who had boarded the train.

The mother’s eyes and mine met as she pointed and aimed her daughter at the seat beside mine — frankly shocking the crap out of me. The youngster, 4 or 5, resisted and cried “怖い!” kowai! (he’s scary / I’m afraid), eyes brimming with fear. She grabbed and clung onto her mother’s leg for dear life, eyes transfixed on me. This response, however, restored order to my world — the world her mother had rocked off its axis by directing her child to sit beside me.

It’s such a rare occurrence that my mind started trying to solve the puzzle. I prayed Mom didn’t mean it as a punishment. I envisioned the little one acting up in a Jiyugaoka candy store, pouting and crying over some sweets she was denied. Behind an embarrassed smile, Mom would have said to herself, “You gonna pay for this outburst, you little ingrate!” And here I am, the perfect foil to dole out some payback!

But when I looked up at the mother, all I saw on her face was genuine dumbfoundedness and humiliation at her daughter’s reaction. I swear she would have died of an overdose if embarrassment were made of aspirin. But there was something else there in her eyes and expression. Not payback. Something I couldn’t get a read on.

Generally, when this kind of thing happens, if I’m acknowledged at all, the parent will adopt an expression that all but reveals they are thinking, “Thank god he’s a foreigner and has no idea what my child said.” It’s almost cute, like this fear is a well-kept secret, and the child's body language doesn’t scream the word's meaning.

At least, I tell myself it’s almost cute.

I braced myself for the next move. How will Mama address this? Reinforce the fear? Ignore it, as if it’s to be expected and nothing can be done about it? These are the two most popular options; I expected nothing less now. I tried to turn away. It sucks to watch this type of irrational fear get normalized day after day. But the rubbernecker in me seized control of my neck and commanded that I “Take it like a grown-up!” So, I took it.

But, to my surprise, this woman did nothing to rationalize the irrational. Instead, she sat beside me and planted her daughter in the seat on the other side of her. She glanced my way, smiled warmly, nod/bowed, and said, “すみません” (Sorry about that. Kids... whatcha gonna do?) I shook my head and waved it off with a sympathetic and indulgent “いいえ” (Don’t sweat it. I work with kids daily, and they say and do the damnedest things).

Then, I caught myself, instinctively, sliding away from her as far as I could, which was only about half an inch or so. This may sound a little ridiculous, but I began this practice as a retaliatory, preemptive strike, anticipating that the person beside me would do it at some point. I just beat them to the punch. But I found ironically that this gesture tended to alleviate some Japanese people’s discomfort at being seated by someone as phenotypically un-Japanese as I am (and there is almost always discomfort). I’m not talking about physical discomfort; generally, there is sufficient space for a person to sit beside me without squeezing in.

Besides, I don’t care about anyone’s physical comfort. It’s a crowded train. Nobody is supposed to be considerably comfortable, and to expect to be, particularly here in Tokyo, would seem unreasonable to me.

I’m talking about mental discomfort, evidenced by the persistent appearance of shifting, fidgeting, cringing, inching away, scratching, and an inability to sit still and relax.

The mother must have noticed me sliding away, for she glanced at me sideways, then down at the little sliver of the seat that appeared between us because of my scooching and smile-bowed again. I just grinned, returned my attention to the iPhone, and decided to write it off as an anomaly for which I’ll likely never get a satisfactory explanation.

Every so often, I noticed, peripherally, a tiny head poking out from the other side of Mom. It was her daughter’s. Whenever I would turn my head her way, she’d duck back behind her mother in that peek-a-boo way children do. Her face was still sour, though, like she hadn’t decided whether I was spooky or not, and she was wondering what the hell her mom was thinking while trying to seat her beside me.

Around the third or fourth time she peek-a-booed me, I waited with my face in her direction for her to re-emerge. When she did, I turned away. Then, I waited for her to duck her head back behind her mother before I turned her way again and waited. After a couple of rounds of this, when she re-emerged, and before I turned away, I caught a glimpse of a smile on her face.

Then, I noticed we were pulling into my station, so I stood to disembark. As I made my way to the door, I turned one last time. The little girl was looking at me. Her fear was gone, replaced by what could have been glee. She waved at me and said, “Bye.” I waved back, glancing at her mother. This time, I could read the expression on her face with ease.

It was gratitude!

And I knew exactly how she felt because the feeling was mutual.

In case you’re wondering, the answer is no. I haven’t made peace with the empty seat. And I never will. I’ve yet to hear a justification for it that doesn’t involve an ignorant race-based presumption or irrational fear, so it continues to reside high on my list of problematic aspects of life here. And no, the frequency of its appearances has not ebbed. Not a lick. It remains a ubiquitous aspect of life here, and I’m as aware of it as ever. So, has anything changed over the past two decades? Does the episode described above represent any change at all? Yes. One notable change resulted in my ability to appreciate this incident thoroughly.

I’ve made some attitude adjustments. Over the years, I’ve come to think of the empty seat as less of an antagonist and more as an ally. The empty seat is a journalist working undercover for an underground news service, reporting daily on the social situation in Japan. And, when I ride the trains and buses, visit cafes, or even walk down the street, I’m tuned in. Unfortunately, this periodical is often the purveyor of dispiriting news. Occasionally, though, it has beautiful stories to share, like the story of a mother who flat-out refused to raise her daughter to otherize non-Japanese in any way. And how she, with a simple gesture and a single word — “sumimasen” — signaled to her daughter (and no telling how many other passengers in that commuter car) her intolerance of the empty seat and the fear that produced it.

I’d like to think that she, like myself, has not made peace with the empty seat, has no intention of letting her daughter make peace with it, either, and felt that during rush hour on a subway car full of the fainthearted was the appropriate time and place to assert her stance.

If so, that feeling, too, couldn’t be more mutual.

All the people who have commented on this issue seem to be men. I wonder if women have had the same kind of experience while riding trains in Tokyo (or Japan). It would be interesting to hear their stories and points of view.

All too familiar of a story. I personally hate bringing the topic up, though not that I make an effort to, as it’s almost always waved away, or excused away for a wide variety of silly reasons. People will contort themselves to provide some explanation beyond the obvious.

I feel I’ve mostly made peace with it, every now and then when the universe is giving me a tough day though it will get a lot more attention from me than I’d normally like to give it.

Most days I don’t notice it but as you described, there are those individuals who will rush onto the train at some stop, get half way to sitting down and notice that it’s a foreigner sitting next to them before they set back up and decide to wander off somewhere else, or just stand.