On a sunny morning in May I visited Kagurazaka, one of the many Tokyo slopes and arguably one of the most stylish districts in central Tokyo.

In ever-changing Tokyo, the few remaining vestiges of the past are being bulldozed out of the way to make space for new steal-and-glass structures. However, there is a place in the heart of the city where tradition is still valued. Welcome to Kagurazaka.

During the Edo period (1603-1867), this relatively small area was located just outside the outer moat of Edo Castle and quickly gained prominence as an entertainment district with numerous geisha houses and restaurants. Some of these houses have survived the many changes and tragedies Tokyo has experienced in the last 400 years, and their presence informs the area’s culture and atmosphere.

Kagurazaka is bisected by the 500-meter long street of the same name that from Iidabashi Station climbs the hill on which it was built. The street itself attracts a lot of casual visitors and tourists. It is also one of the district’s less interesting spots as many of the local shops and eateries have been replaced by the usual fast food joints and chain restaurants and cafes that can be found anywhere else.

A curious feature of this street is that it is an “alternate one-way road” meaning that in the morning the car traffic only goes downhill while in the afternoon it switches direction (it is also completely close to traffic between 12:00 and 13:00, and from 12:00 to 19:00 on Sundays and public holidays).

The one-way system was established in 1956, at a time when the street had no sidewalks and people complained about the dangers of negotiating the narrow slope through heavy two-way traffic. According to urban legend, this particular alternate pattern was devised to favor powerful politician (and future prime minister) Tanaka Kakuei who commuted daily from his house in Mejiro to either the National Diet or the Ministry in the city center.

The most influential member of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party from the mid-1960s until the mid-1980s, Tanaka Kakuei was a central figure in several political scandals, culminating in the Lockheed bribery scandals of 1976 which led to his arrest and trial.

Historical curiosities aside, the real heart of Kagurazaka is hidden in the maze of winding back alleys and narrow stairs on both sides of the slope where the kagai (“flower town” i.e. geisha world) is still quietly going about its business – though mostly unseen by casual passersby.

Atami-yu features the temple-like double roof typical of many traditional public baths.

Walking uphill, let’s take the second street on the left. We quickly reach Atami-yu, a public bath that used to be a sort of meeting place for the tightly woven community of people who lived and worked in the area.

Atami-yu is flanked by a coin laundry on the left and one of Japan’s ubiquitous vending machines. Following the district’s traditional vibe, this one is aptly decorated with a geisha and carps.

Another common feature of many Japanese neighborhoods are the colorful election posters sporting the rather dumb-looking mugs of local politicians. On the right, under the white board, Atami-yu lists the rules of engagement for public bath patrons during the pandemic: talk as little as possible and do not stay long.

During the 1950s, according to the owner, about 200 geisha used to visit every day, when Kaguraza was one of Tokyo’s many thriving entertainment centers and private baths were a rare luxury. Those were the years when geisha-turned-singer Kagurazaka Hanko scored a big hit with the song “Geisha Waltz.”

Atami-yu is strategically located at the foot of the picturesque Atami-yu Kaidan (Staircase), also called Geisha Alley because it connects the public bath to the Kenban, the office where geisha practice.

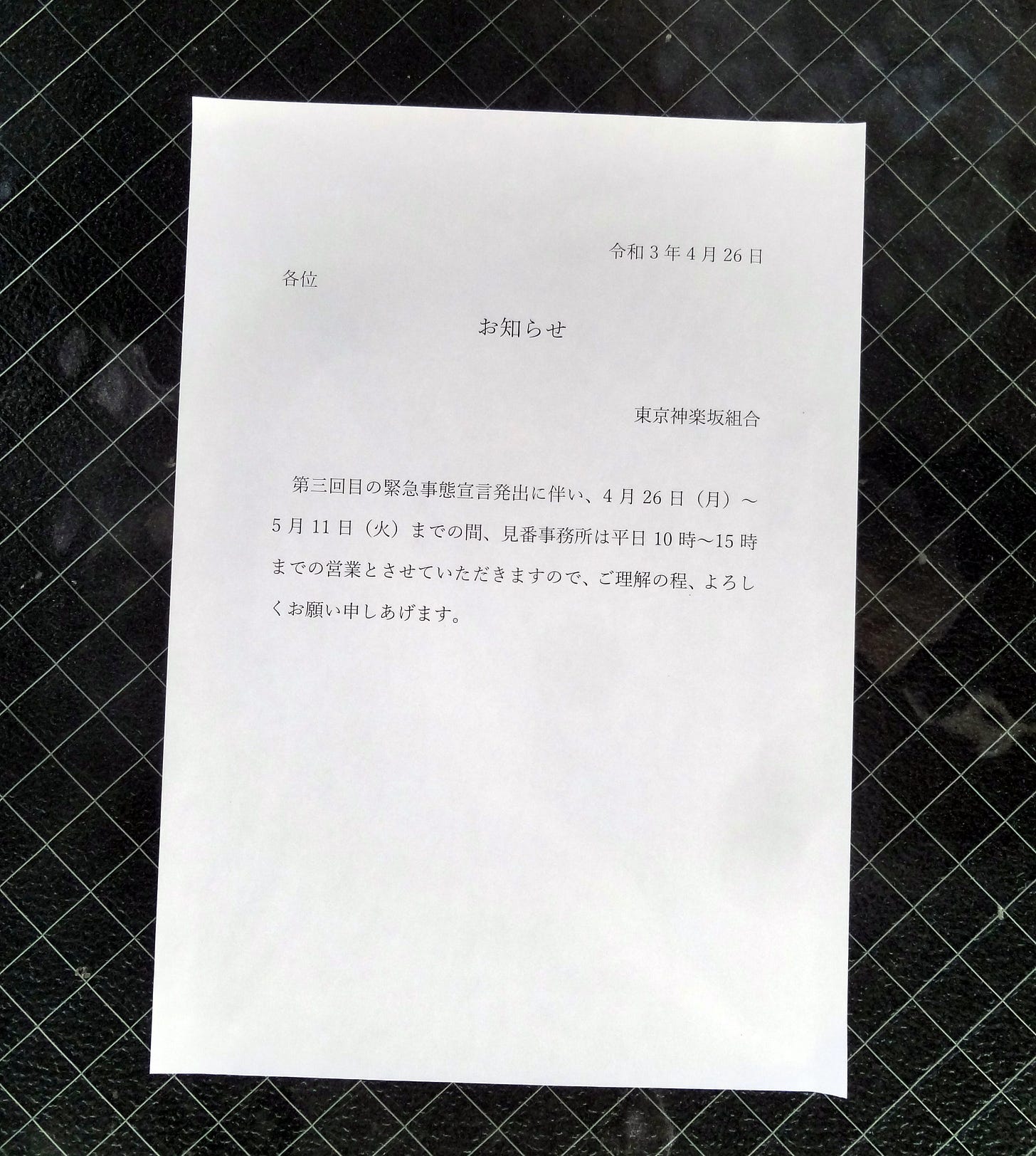

This nondescript two-story building also houses the office that manages geisha’s work and acts as a broker between the geisha houses and the ryotei (traditional restaurants) where they meet their clients.

On the day I was there, a note on the door announced that as the city was in the midst of the third wave of the pandemic, business hours would be limited between 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m.

Close to the Kenban, Fushimi Inari Shrine is also called Hifuse no Oinari-san, a reminder that hifuse (fire protection) was and still is a priority in an area with a high concentration of restaurants and where many houses are still made of wood.

Here you can always be certain to find small fox statues as these animals are Inari’s chosen messengers and serve as guardians against evil spirits.

Kagurazaka’s kagai was first established in 1857 and thanks to its vicinity to both the city’s political and economic centers, it developed into the number-one downtown entertainment district so much so that it became known as Yamanote Ginza. Quite miraculously, the local establishments escaped the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake almost unscathed, and in the 1930s, about 600 geisha were working for 150 ryotei.

That was a time when the sound of the shamisen could be heard everywhere and after the sun set, the streets were full of the people who lived in the nearby mansions. Between shopping, dining, going to the movies or attending a stage performance, Kagurazaka was synonymous with fun.

According to Sakurai Shin’ichiro, former president of the Kagurazaka Association, the district remained active well into the Pacific War, but when the situation changed for the worse, the geisha had to join the Women’s Volunteer Corps and his family had to lend their ryotei to a Manchuria-based electrical construction company. Kagurazaka was razed to the ground by the American air bombings, but it quickly resumed business soon after the war. When Katayama Tetsu of the Socialist Party became prime minister in 1947, he ordered all ryotei to stay closed, but the owners kept letting customers in from the backdoor.

Eventually, the geisha world proved more resilient than the government (probably because the ryotei offered many politicians and entrepreneurs a discreet place where they could conduct their high-level meetings) and in the years of high economic growth, the area returned to its prewar heyday. Still, by the early 1960s, the number of geisha had halved to about 250 and the ryotei had shrunk to 50.

Today, only a handful of geisha remain (there were 18 in 2016, ranging from 20- to 70-year-olds), working for the four surviving ryotei. These exclusive restaurants are located on the right side of Kagurazaka Street and now as before only accept new customers by referral. But before crossing the main street, let’s pay a visit to Kagurazaka’s main religious spot: Zenkokuji.

Guarded by a pair of grotesque-looking stone tigers, this Buddhist temple is devoted to Bishamonten, one of the Seven Gods of Luck and, according to local belief, the source of Kagurazaka’s fortunes. Zenkokuji even makes an appearance in Botchan (1906), arguably Natsume Soseki’s most famous novel, where the protagonist attends a fair in the temple grounds and catches a carp only to drop it an instant later.

O-mikuji are random fortunes written on strips of paper. When the prediction is bad, it is a custom to fold up the strip and attach it to a pine tree or a wall of metal wires alongside other bad fortunes in the shrine grounds. A purported reason for this custom is a pun on the word for pine tree (松, matsu) and the verb 'to wait' (待つ, matsu), the idea being that the bad luck will wait by the tree rather than attach itself to the bearer. (From the Wikipedia)

Just across the street from the bright-red gate that marks the entrance to Zenkokuji, you would be forgiven for failing to notice a very narrow passage between two shops, barely wide enough to let a person pass through.

That’s the magical door to Hyogo Yokocho (Arsenal Alley). During the Sengoku (Warring States) period, weapons merchants lived here (hence its name) but today the area is home to the surviving ryotei, other refined-looking restaurants and a few traditional hotels.

Walking these cobblestone paths is one of those rare pleasures that can only be enjoyed in Kagurazaka. The district’s right side is a veritable maze of narrow alleys and dead-ends – including the aptly-named Kakurenbo Yokocho where losing your way is part of the fun.

Kakurenbo means hide-and-seek and apparently got its name because it’s the perfect place to hide from prying eyes. Indeed, try to follow a visiting VIP into the geisha district and you are bound to lose him once he enters the black wood-walled labyrinth.

Nowadays, crossing paths with a geisha in Kagurazaka is not as easy as in Kyoto.

Chances are this particular beauty wasn’t even a geisha but just a model out for a photo shoot.

One of the area’s most famous hotels is located toward the end of Hyogo Yokocho. Wakana is an old ryokan (traditional inn) with a storied past. Opened in 1954, for many years Wakana welcomed novelist and scriptwriters who needed some measure of privacy and inspiration to produce their work. Yamada Yoji and Terayama Shuji are but two of the many creatives who have spent a few nights in one of its five tiny rooms.

If you want to follow in their footsteps you will have to be patient because Wakana is being currently renovated by Kuma Kengo.

The world-famous architect is a familiar name in Kagurazaka: not only he lives in the area but his firm has recently renovated Akagi Jinja, a Shinto shrine that was originally built during the Edo Period by a wealthy immigrant from Gunma Prefecture.

The shrine’s new version is a unique take on the traditional shrine model, all glass and polished wood.

It’s also one of the few concessions to modernity and exoticism that the locals have allowed through the years. The other noticeable foreign element is the pervasive but understated Gallic presence, mainly in the form of bistros and other eateries extolling the joys of French cuisine.

Kagurazaka’s French Connection goes back 70 years, with the establishment, in 1951, of the nearby Institut Francais. But even before that, in 1947, the Librairie Omeisha had opened in a quiet street on the other side of Iidabashi Station. French expats soon followed, and with them a host of eateries that catered to their tastes – and the refined palates of the locals.

Kagurazaka’s fascinating mix of Japanese and European elements notwithstanding, tradition still dominates, modernity is only allowed in small doses, and the urbanscape is still dominated by two- and three-story buildings. The one big exception to the rule – and the source of endless complaints – is the mammoth apartment building – an 80-meter, 26-story “tower mansion” – that rose in 2003 beside Jinai Park.

By the way, the place where this tiny, rather unprepossessing park now stands has played an important role in the history of Kagurazaka. As the name suggests, this spot was originally occupied by a temple, Gyoganji, where major historical figures such as Ota Dokan came to worship the goddess Senju Kannon. In front of the temple gate was an inn, and every time the third shogun Iemitsu came to practice falconry, he stopped there for a quick meal. Then, around 1857, a part of this area became a place of excursion and leisure and led to the establishment of the geisha world. Many artists, entertainers and celebrities were said to be regulars. Among them, the aforementioned Soseki later wrote a few essays (featured in the 1915 collection Inside My Glass Doors) where he reminisced about the days when, as a child, he used to play in the temple grounds with his cousin.

Eventually, in 1907, Gyoganji was moved to another location in Tokyo, leaving behind the tiny park and, now, the ugly condo.

Kagurazaka has had a long and intense love affair with many artists and literati who lived in the area. During the Meiji and Taisho period (between the mid-19th century and the early 20th century) it was portrayed in words and paintings by the likes of Ozaki Koyo, Izumi Kyoka and Kaneko Mitsuharu. Izumi, in particular, was closely related to the geisha world and even wrote a book, Onna Keizu, based on his relationship with a geisha.

A patch of grass and a plaque is all that remains of Izumi Kyoka’s former residence.

Kagurazaka has also been chosen as a location for several screen works. For example, Hana wa Hanayome – a pun on hana (flower) and hanayome (bride) – is a 1971 TV drama about a geisha working in the district who marries a local flower shop owner. Popular actress Yoshinaga Sayuri played the protagonist and learned from a real geisha how to move and behave.

More recently, Ninomiya Kazunari (a member of the uber-popular idol group Arashi) has starred in Haikei, Chichiue-sama (Dear Father), a 2007 TV drama chronicling the vicissitudes of a long-established Kagurazaka restaurant that struggles to survive amid the changing times.

So far we have seen Kagurazaka’s “main attractions” but you can just have fun by taking a back alley at random and getting lost. You never know what you may find behind the corner. Maybe some little details from the past.

This is, by the way, the main theme of the Tokyo Detour thread: whenever you find a promising, interesting-looking alley or even a dead-end street, leave the main path and just go for it.

Like this one, for instance. That’s what I found when I climbed the creaking stairs of that two-story condo.

Before going out, don’t forget to turn out the light and gas, and lock your door!

Knock, please.

For those who feel more adventurous, the district’s charm extends beyond the alleys immediately surrounding the main street. If you walk in the direction of the Ushigome-Kagurazaka subway station, for instance, you will arrive at Wakamiya Hachiman Shrine. It was here that kagura (sacred music and dance) was performed back in the day.

This has always been a high-class residential area, and even today it retains the look and feel of old money. Here you will not find any high-rise condos because the long-time residents are reluctant to sell their land. They have lived here for generation and will probably die here.

If you stick your nose into dead-ends and behind corners long enough, you may find two relics from the 1950s that have been registered as tangible cultural properties by the Agency for Cultural Affairs: the Suzuki Family residence and Issuiryo.

The latter structure was built in 1951 as a carpenter's dormitory. It was later turned into a rental apartment and is currently used as an office. Both houses are rare, beautiful examples of Showa Retro – veritable dinosaurs in terms of Tokyo architecture. They have been recently reinforced against earthquakes; so hopefully, they should be around for a while.

These and other hidden treasures can be found in Kagurazaka, a little piece of old Japan where time may have not stopped but it has slowed down to a leisurely pace. In 1930, the hit song "New Tokyo March" sang the praises of the little hill where Bishamonten’s presence could be felt and the alleys where full of cute maiko (apprentice geisha) and potted plants. The maiko may be gone, but Bishamonten, the flowers and Kagurazaka’s magic atmosphere are still there.

If you enjoyed my post, please share it as much as possible

And consider subscribing to Tokyo Calling. Thank you.

Wow, what a loving tribute to Kagurazaka. I’ve lived here 20 years, and it is where my wife grew up, so we feel a deep connection to this neighborhood. I learned a lot from your article, and it kindled my love for our family’s home even more. Thank you for all the research and wonderful photos, Gianni.