Naturally yours

A conversation with architect Kuma Kengo

Hello there! As during my Kagurazaka walk I mentioned architect Kuma Kengo twice, I thought you might be interested in reading my interview with him. This article originally appeared in French in Zoom Japon magazine.

As usual, if you like it, please share it widely

Internationally renowned architect Kuma Kengo is in hot demand these days. Besides designing such high-profile Japanese buildings as the new Olympic Stadium in Tokyo and the Hiroshige Museum of Art, Kuma’s 300-strong studio (spread among offices in Tokyo, Beijing, Shanghai and Paris) is behind the City of the Arts in Besançon, the FRAC in Marseille, the Conservatory of Music in Aix-en-Provence and the V&A Dundee in Scotland.

I paid a visit to Kuma-san at his Tokyo office to talk about his architectural philosophy and one of his many books, L’architecture naturelle, which was recently published in France.

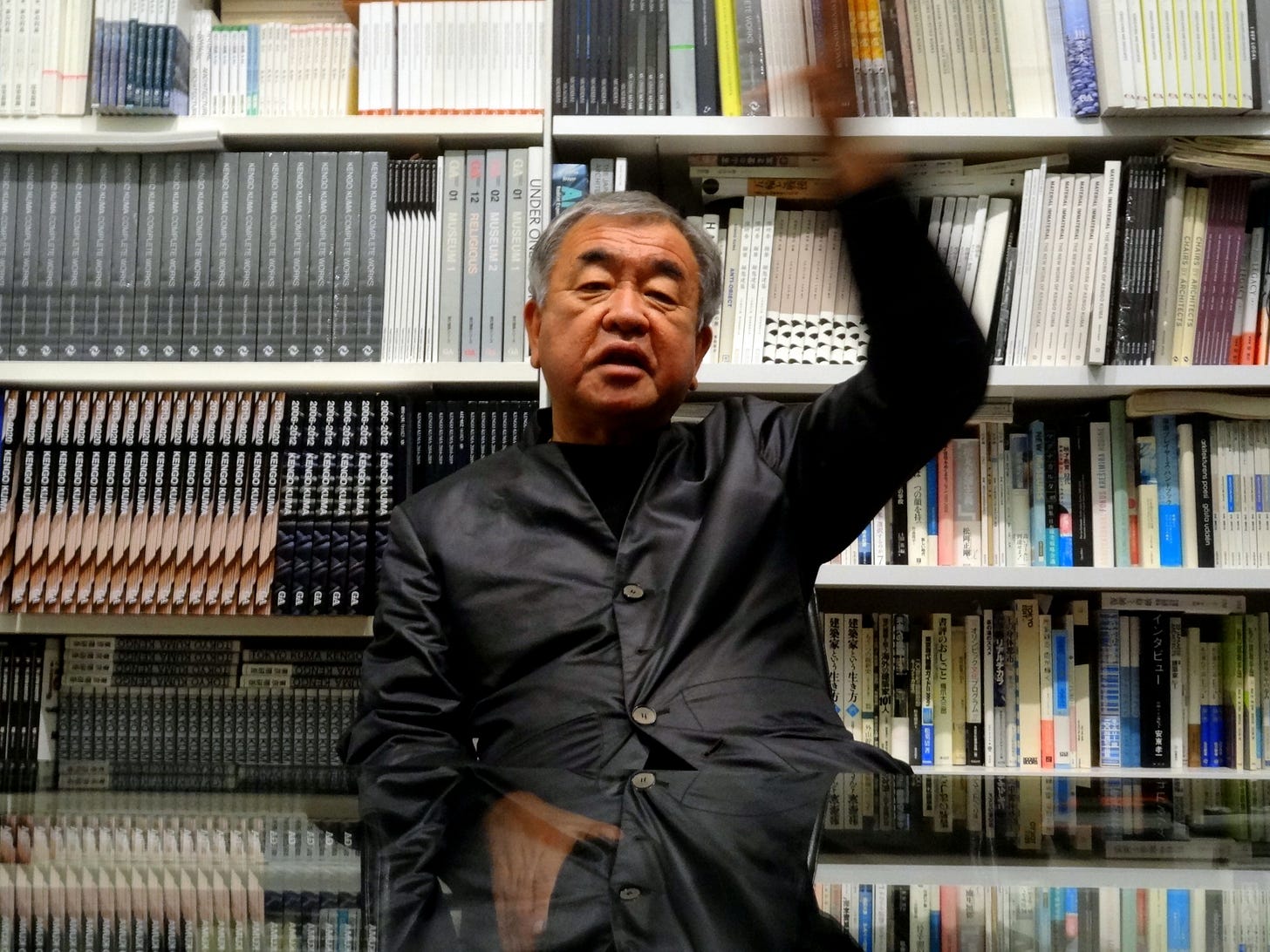

We met in a glass-walled meeting room full of books perched on top of the four-story building that houses Kengo Kuma and Associates’ headquarters.

On the east side, one enjoys an open vista on the Roppongi Hills-Tokyo Midtown skyline, while if you walk on the opposite direction, a 15-minute walk takes you to Kuma’s brand-new Olympic Stadium.

What is your book L’architecture naturelle about and why did you write it?

The book is divided into eight chapters in which I focus on a different project and a different material. It’s at the same time a subjective history of architecture, a manual of practical application and a reflection on the meaning of architecture. Today’s urban landscape is made of big boxes made of steel and concrete. However, these materials have been only in use for about 100 years. Indeed, they are the signature materials of the 20th century. I believe that we should take architecture back to the past. Cities made of steel and concrete are not good for people. A return to natural materials would both improve our mental health – our souls – and the economy. So I wrote this book, back in 2008, to show how architecture can coexist with nature; how we can achieve a successful marriage of architecture and place.

So this is what you mean when you say that "architecture should be part of nature"? Yes, you only need to observe animal life to see that their living spaces merge naturally with their surroundings, they are part of nature. Birds, for instance, make their nests in the trees. We are living beings too, but we tend to separate our houses from the surrounding environment. I believe this is a mistake on our part. We should see architecture as part of nature and try to live in communion with, not in opposition to it.

Speaking of natural materials, in recent years the activity of Kengo Kuma and Associates has been connected to the use of wood. However, your studio has been experimenting with many different materials including textiles.

I love soft materials. Even wood is rather soft and yielding when compared to concrete. For example, if you fall on a concrete floor you can get badly hurt but a wooden floor is more forgiving, more “friendly.” It’s also warmer and more pleasing to the touch. In this respect, textiles are even softer and nicer. That’s why I like to work with it. A good example of how we can use textiles in architecture is the new Takanawa Gateway Station in Tokyo where a mixed frame made of steel and wood supports a textile membrane. In our studio, we now have a member of the staff who specializes in textiles. After majoring in architecture, she studied fabrics at the office of Dutch textile designer Petra Breese, and now she is in charge of fabric material development at our office.

I believe we should take nature back to the past: architecture can coexist with nature.

On the other hand, textile, by its very nature, has problems of durability and doesn’t seem the ideal material to be used in architecture.

That’s true. Its performance can also be greatly affected in a windy environment. But technology has helped in making stronger, more resistant types of textile, and once we can improve air control, we can use fabrics in many creative ways. The material we use is actually very strong. Textile’s great advantage over other materials is that it has a relaxing, soothing quality on people. When you think about it, human beings used clothing before building architecture, and protected themselves with cloth. In this sense, fabrics go a long way back to our primitive life. It is cloth, rather than architecture, that protects people mentally.

Tell me about the importance of "ma" and transitional spaces in your projects.

Modernists divided human life into different environments with different functions, but when we go about our daily life, these divisions are meaningless. Human life is in a state of constant flow. This is why I’m going the other way and try to integrate all these places and functions.

“Ma” or “void” is a space that puts you in direct contact with your surroundings. Traditional Japanese architecture makes no distinctions between indoors and outdoors. Instead of fixed, thick walls separating people from their natural surroundings, traditional houses have lots of “transitional spaces.” For example, we have sliding doors that open up onto a garden and let the wind blow through the house. Then there is the engawa which is an open corridor or veranda that depending on how the sliding doors are arranged can be either outside or inside the house. Today’s houses are boxes that don’t allow the kind of direct contact with nature that transitional spaces make possible.

When possible, I always try to include these transitional spaces. Take, for example, the Besancon Art Center that we built on the riverside of the Doubs. We had to work with existing structures, namely a 1930s bricks warehouse and the 17th-century pentagonal bastion of the Vauban Citadel. We didn’t want to create a simple box like those that proliferated during the 1980s. Instead, we proposed to link the existing buildings with a “loose” roof to the gorgeous riverside, thus giving unity to a site characterized by heterogeneous elements. Most importantly we created a special space under the roof where the wind from the river could blow and pass through.

Another project where we were able to apply the same technique is the V&A Dundee on the city’s waterfront. We opened a cave through the center of the building to connect the beautiful nature of the River Tay with Union Street, the axis running through the town of Dundee. This hole made it possible to extend the activities of the city out to the waterfront, and now the river has reclaimed its role as a promenade. Using a void to strengthen the connection between nature and people is actually an idea that is already found in Shinto shrines where the torii or gate acts as a gateway to the shrine.

Kuma Kengo is a prolific writer and the room where we met was full of multiple copies of his books.

“Ma” is a typical Japanese concept. How much influence has traditional Japanese architecture had on your work?

I grew up in a traditional Japanese house. I used to sleep on a tatami mat floor, enveloped in the smell of straw, and the smell of the clay walls. So you could say that Japanese tradition is not an architectural style for me but it exists in my body. In the past I actually wasn’t that fond of traditional architecture. It “smelled of old,” as we say in Japan. Then, in the 1990s, the economic bubble burst and investment for architectural projects in the big cities suddenly dried out. So I turned my attention to small towns and the countryside and rediscovered the charm of tradition. That’s when I realized that the past was the new future and I had to change my approach in that direction.

In Asian philosophy, mankind is dwarfed by the majesty of nature whereas in the West, man is a master of nature and changes it any way he likes. I find that this lack of respect for nature is what has led the world to the current situation. We need to change our approach if we want to survive on this planet.

The National Stadium is a hybrid of wood and steel. In the future, will it be possible to build structures entirely made of wood?

Of course. Technology is changing the way we make buildings. Currently, the most talked-about building material is called CLT (cross-laminated timber) which is made by laminating layers of lumber cut from a single log. By gluing layers of wood at right angles, the panel is able to achieve better structural rigidity in both directions. Using CLT has made it possible to build medium-rise buildings made of wood. However, there is still a problem in terms of cost. When CLT becomes more popular the cost will naturally decrease, and I think that wooden buildings will be built with the same budget as steel structures.

Also, we can now use new kinds of wood that are resistant to fire. Even in Besancon we used that kind of material.

What do you think of the Olympic Games?

It’s a difficult issue with no easy answer. However, as far as the stadium is concerned, the funny thing is that we designed seats that, even when there are few people, give the impression that the place is crowded. The project, of course, was completed before the COVID-19 pandemic so it was just a fortuitous decision on my part. The fact is that I don’t like arenas where all seats are the same color. So I opted for multicolored seats, and they really give the impression people are seated even where there is actually nobody. In this respect, even if they decide to limit admissions for safety reasons, the place shouldn’t look so lonely.

How do you judge Tokyo from an architectural point of view and as a living environment?

First of all, it’s because I grew up in Tokyo that I became an architect. The first Tokyo Olympic Games were held in 1964 when I was ten. One day, my father took me to see the Tange Kenzo-designed gymnasium. He loved the design very much. It’s a beautiful masterpiece. Structurally it’s very challenging. The roof is suspended between two concrete columns. There’s a big cable connecting them, and it’s beautifully curved. It’s a very functional solution but at the same time it creates a beautiful shape. The exterior is lovely, but I was shocked by its interior, with its high ceiling, and the natural light that seemed to come directly from heaven and reflected on the water surface. In fact, an American diver said he felt like being in paradise. Before I visited Tange’s gymnasium, I actually wanted to become a veterinarian because I loved cats very much, but when I realized there were people who made buildings, I changed my mind and decided to become an architect.

They say that Tokyo is an ugly, chaotic city without any defined urban plan. Maybe it’s because I grew up here but I quite like its randomness. For example, if we compare Tokyo and Yokohama, where I was born – especially their city centers – generally speaking I prefer Tokyo. Yokohama, in comparison, looks more like a copy of a Western city, and I don’t find that particularly attractive. In Yokohama, I much prefer Chinatown’s chaos. When I was a little kid I often went to Chinatown with my family. Then, from there we would climb the hill in Motomachi. That’s the part of Yokohama I still like the best.

In the future, I would like cities to be greener and have fewer cars. Cities are meant to be walked and explored.

In Tokyo, of course, there are areas I like and areas I don’t. For example, I like the winding little streets and the slopes in Kagurazaka, where I live. I like the alleys where people put flowerpots outside their doors. On the other hand, I don’t like the office and commercial areas and those wide avenues devoid of character. Too many concrete buildings are being constructed in Japanese cities purely for business purposes. In my opinion, this has been destroying cities for the past 60 years and I want to stop us from heading in this direction.

In the future, I would like cities to be greener and have fewer cars. Cities are meant to be walked and explored. Japan’s population is gradually shrinking and getting old, and according to the media, more traffic accidents are caused by elderly people. I think they should put their cars away and just walk.

In the end, though, living in the city can be very stressful. Even though I like Tokyo, I need to leave the city once in a while in order to recharge my batteries. I usually spend the weekend at my villa in Kiyosato and be surrounded by nature. Currently, I’m working on projects both in Hokkaido and Okinawa, and this is another good excuse to have a change of scenery and get away from the maddening crowds.

How was it working on the Takanawa Gateway Station project? What did you want to express with it?

This is not the first railway project I worked on. Previously, I had already built a station made of wood, and Takanawa Gateway gave me an opportunity to replicate this approach on a bigger scale in Tokyo. Again, at the risk of repeating myself, I think that railway stations shouldn’t be enclosed environments isolated from the rest of the city. The typical Japanese model is a station with ticket gates that become de facto barriers separating what’s inside and what’s outside. In comparison, many European stations are more open and welcoming; people can freely go in and out. In the future, with the help of IT technology, Japanese stations can become the same kind of open places. I’ll go as far as to say that stations may become Japanese cities’ most fun places.

How do you see the future of architecture?

In the 20th century, architecture was seen as an industrial product; something that could only be created by using huge machines. Now, I think, there is a gradual return to handicraft and smaller, manageable homes. The time will come when people will build their own homes and gardens again. In the past, a lot of people, even in Tokyo and other major cities, tended their own little gardens. Unfortunately, many have given up on this healthy habit, and this, in return – the loss of direct contact with nature – has been a source of stress.

Design today should have a connection with society. I mean, social responsibility is a big part of design. In the 20th century the role of the architect was to design beautiful objects. If a building attracted people’s attention, it was a success. But now we are living in a very complicated society, and economically it’s not an easy period. So people look at architecture with different eyes. For example, is that building really useful or necessary for the community? So the architect should be responsible for that kind of issue.

Many thanks, Kuma-san, for the nice chat. And thanks Eric Richsteiner for taking the picture above.

As usual, if you liked this story, please share it widely.

And consider subscribing to Tokyo Calling! Thank you - Gianni.