Hi there, how are you?

Here in Japan, the rainy season isn’t over yet but it’s getting hotter and muggier day by day and my wife keeps complaining about the weather. To which I reply, do some autogenic training. Instead of grumbling and cursing the rising temperatures, keep telling yourself “it’s so cool today… it’s so cool today…”

Of course, she never listens to me. However, this got me to think that it would be nice to publish an unseasonably winter tale, for a change.

Let me know if you enjoy this true, tragicomic story from many years ago.

Here I was, sitting at a low table in the big tatami dining room of a ryokan, at 8:00 a.m. on New Year’s Day, wondering what I had done to deserve all this and trying to find a way out of this f#@ed-up situation…

[Flash back]

It was a bleak December. My wife and I had not planned anything for the end-of-the-year festivities. Now it was too late to make reservations and we were feeling bored and frustrated. Then, around the middle of December, my wife had an idea: let’s choose a destination that is both close to home and not very popular with the masses. Theoretically it was a great idea, given our hopeless situation. Then we took a look at the map and realized that the only feasible destination was Chiba Prefecture.

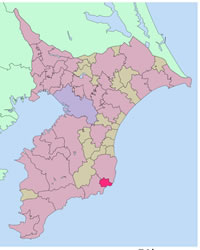

Chiba Prefecture occupies the Boso Peninsula east of Tokyo. On the upper left corner, you can see Tokyo Bay, three of the capitals’s main rivers (the Sumida-gawa, Ara-kawa and Edo-gawa, and some of Tokyo’s artificial islands.

For those who don’t know it, Chiba occupies a peninsula just east of Tokyo. Its west coast faces Tokyo Bay; the east coast, the mighty Pacific Ocean. In the middle, there are mildly inviting woods and mediocre tourist spots. In few words, it’s a long list of broken promises. Thinking about Chiba always reminds me of a guy I used to know back in Italy. He was tall, had blonde hair and blue eyes, but at first glance you could see he was no Robert Redford. Anyway, we hardly had any alternatives, so we reserved a ryokan in Onjuku, on the east coast, to spend the New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day.

Onjuku is that red spot on the map. Please, don’t bother.

On December 31st we took a ferry across Tokyo Bay and toured the peninsula by train, stopping here and there to admire the local “beauties.” At any rate, we were just happy not to be at home, and the day was sunny and not too cold, considering the season.

Seen from afar, Onjuku isn’t half bad (photo courtesy of Yoshikazu Takada) (yes, among other things, I had forgotten my camera at home).

We reached Onjuku at about 3:00 p.m. and found themselves in a semi-deserted town (I guess most of the people had left for better destinations) full of palm trees and Mexican-themed stores.

Maybe not very Mexican-looking, this one. Still, quite unsettling… especially the store’s name (photo courtesy of Yoshikazu Takada).

Even the streets we took to reach the ryokan were punctuated by sombreros, cacti and other Mexican symbols. It turns out that Onjuku is a sister city with Acapulco, which not only makes me laugh, but at the moment made the whole situation even more surreal.

Palm trees galore (photos courtesy of Izu Navi).

Admittedly, people love the place in summer (photo courtesy of Yoshikazu Takada).

When we reached our ryokan, we soon learned what my wife had feared all the way from home, that is, the spa in our hotel was no spa at all. It was a fake; the hot water in the tub was just common tap water. The horrible truth about is, we may be living in a doomed volcanic archipelago that literally sits on a deadly mix of sulfur, lava, and ever-shifting tectonic plates, but this is one of the few places that does not have a single natural spa. Which somewhat explains why we could find a room at such a short notice.

So we left our bags in our tiny room and headed for the beach. The sun was already setting, and we were welcomed by a strong, freezing-cold wind that cut through our coats and filled our eyes with tears. To add to the already Twilight Zone-like atmosphere, we discovered the statues of two camels in the middle of the beach.

Dali couldn’t have done better (photo courtesy of Kasadera).

Apparently, according to the local tourist information office, this was one of the strongest selling points of the whole Onjuku experience. At this point we expected to see Salvador Dali materialize in front of our teary eyes, but we only saw a mustached old man.

Get a load of this. Try to find this stuff in Acapulco.

I was happy to leave the place and go back to our warm shelter. It was only after dinner that I learned that the end-of-the-year festivities were going to take place on that same beach. When we reached it at 11:00 p.m. it was pitch dark, still windy and much, much colder. The local folks lighted three huge pyres that gave the whole setting a picturesque if rather haunted atmosphere, but did little to make us warm. The Japanese, stoic as usual, lined up in good order to get 1) one tangerin, and 2) a cup of sweet sake, and then listened to the Shinto priest recite some loooooooooooooooong endless prayers. I prayed for the whole party to end soon, but in vain. At 2:00 a.m. I was back at the ryokan, under a mountain of futons, trying to bring my frozen hands back to life.

Different time, different place (Wakayama Prefecture in February) but you get the idea. If you want to learn more, check out “visual journalist” Nicolas Datiche’s excellent website.

One of the characteristics of these traditional inns all over Japan is that, regardless of the time of the year, they serve breakfast at impossibly early hours. I mean, I’m supposed to take it easy here. Sleep long and relax – especially on New Year’s Day. If I had been in Italy (my home country) I would have likely woken up at 11:00 a.m., skipped breakfast and sit in front of the TV to watch the not-to-be-missed concert from Vienna, Austria, while waiting for the lunch to be ready.

One of the characteristics of traditional inns all over Japan is that, regardless of the time of the year, they serve breakfast at impossibly early hours.

I guess the owner understood the situation and moved breakfast time one hour later. So here I was, sitting at a low table in a big tatami room at 8:00 a.m., trying to keep my eyes open and wondering what I had done to deserve all this. I completely woke up when my flaring nostrils caught the smell of the food being served.

This is good… provided I don’t have to eat it for breakfast.

Now, before you label me an ignorant chauvinist, I want to point out that 1) I love Japanese cuisine; and 2) I love the healthy approach to eating of the Japanese. Give me fish and rice every day, but NOT at 8:00 in the morning! I’m an Italian, for chrissake! We Italians eat bread and jam and cookies for breakfast. Even salad and scrambled eggs sound like torture to our ears.1 Unfortunately for me,

the Japanese think that eating sweets for breakfast is like doing unnatural acts with a hen or a sheep.

So as I was saying, here I was, my legs already cramping under the low table, my brain still half-asleep, but my eyes wide open, contemplating with horror a big tray full of dishes, and my stomach groaning desperately and trying to hide behind some other organs. This being a special day, the owner had decided to go out of his way to please the customers. We got grilled fish, all-you-can-eat white rice, a raw egg to break on top of it (I absolutely despise raw eggs, by the way), miso soup, seaweed, tomato salad, scrambled eggs, and fake bacon. And then came the piece de resistance, osechi.

Say NO to osechi (photo courtesy of Ocdp).

So welcome to osechi-land, a parallel culinary universe where few people dare to trade. Told in few words, osechi is the traditional cuisine that the Japanese prepare for New Year’s Day. Please note my choice of words. I say ‘prepare’, not ‘eat’. Apparently, all the good Japanese mothers (at least of a certain age) prepare this colorful food. They spend the good part of New Year’s Eve cooking an endless number of dishes and arranging them on special trays. The saying goes that you cannot call it New Year’s Day if you don’t have osechi on your table. The curious thing, though, is that most of the time it does stay on the table, because only few people actually eat it. The old timers and the fathers in the family love it, but all those under fifty usually skip it and prefer to attack more plebeian but palatable food.

My wise and lovely wife has never made it since we started living together, and I love her all the more for that. My two sons are famous for eating anything remotely edible, and even some inedible stuff that only children can stomach, but every time we have lunch at my in-laws, they only give osechi a passing look and proceed to dive into sushi and tenpura.

But now I was in this hotel, and the only gaijin at that, and everybody was looking at me to see if I was up to the challenge. So I had to grin and bear it. Luckily everybody was still drunk from the night before and nobody seemed to notice that after the first couple of mouthfuls, I only pretended to eat the damned stuff and dumped it instead into a tissue. Sometimes you gotta do what you gotta do.

Technical Notes

Still want to know what the hell osechi is? Here are some of the dishes that you will likely find in those trays:

tazukuri: dried sardines cooked in soy sauce. Very sweet and sticky

kamaboko: broiled fish paste

kuri kinton: chestnut-based paste

kuro-mame: sweet black soybeans

daidai: Japanese bitter orange

datemaki: sweet rolled omelet mixed with fish paste

kazunoko: herring roe

konbu: a kind of seaweed. Thicker and harder than other varieties

white radish- and carrot-based pickles.

As you can see, the keyword here is ‘sweet’. The Japanese put sugar almost everywhere (this stuff has to last for at least three days, after all), and in doing so ruin everything. Plus they add other typical condiments such as mirin, a slightly sweet kind of rice wine similar to sake, whose strong flavor is guaranteed to ruin every dish they add it to.

Last but not least, we have every emergency room’s favorite dish:

Ozoni: a soup containing mochi (rice cakes)

Here’s something I found online: Everyone has their own New Year’s traditions, and one of Japan’s involves eating a stretchy mochi rice cake known as ozoni. The metaphor behind it has to do with the promise of a long life, but those who don’t take the proper precautions during their meal often find it has the opposite effect.

This proved the case once again this year, in which almost a dozen Tokyo citizens aged between 27 and 98 were taken to the hospital after choking on the New Year’s treat. Over half of the victims were older than 60, including the sole death in the group, an Akishima City resident in his 80s.

While the rest survived the choking incident, they still had to deal with a severe choking hazard thanks to the way mochi can easily get lodged in one’s windpipe. Since ozoni is often served in a hot broth, it’s much easier to unintentionally swallow pieces that are much too large, posing a threat for people of all ages, especially young children and senior citizens.

So there you go. Then don’t say I haven’t warned you.

As usual, if you liked this piece, please share it widely. You will earn good karma points.

And you may even want to subscribe. It’s FREE.

I couldn’t agree more with Christopher Ross when, in Mishima's Sword: Travels In Search of a Samurai Legend, he says that “of all meals, breakfast is the meal one is least inclined to experiment with.” After all, early morning is “when the duplicitous mind is still half asleep and when we are inclined to visceral reactions.” Where our opinions differ is when he says that whenever he has actually tested his breakfast intolerance, like having grilled salmon in Japan, he has felt “a new horizon has dawned.” Well, more power to him. What I know is that I’m an extremely tolerant person, but my stomach is a grumpy fella, particularly after a few hours’ sleep.