Hi there, it’s a crisp beautiful morning here in Yokohama. It’s 8:38 and I’m listening to the Beatles’ “I’m only sleeping.” The response and feedback to the first part of this story have been awesome, with nearly 200 views in just a few days and a few nice comments. Please subscribe and keep sharing and spreading the word about Tokyo Calling!

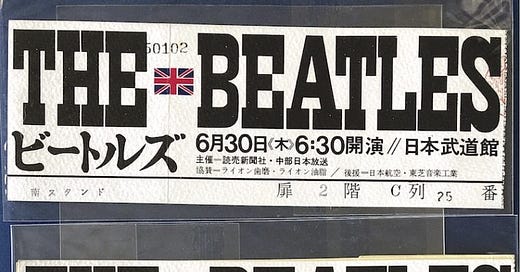

The photo of the concert tickets was taken by Eric Rechsteiner for ZOOM Japan.

In February 1965, Toshiba’s music department sent an invitation to the Beatles to play in Japan and tour plans were quickly developed until an official announcement was released on 15 March, two weeks before Rubber Soul came out in Japan.

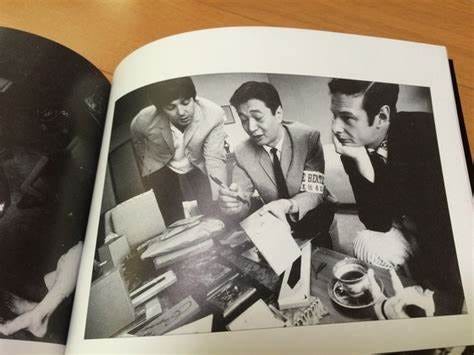

More than Brian Epstein, the group’s manager, the two men who made the Japanese tour possible were Victor Lewis and Nagashima Tatsuji. Lewis was an ex jazz guitarist and London theatrical agent who had moved in booking management. He had worked with Epstein on the breakthrough 1964 US tour, and in 1965 his agency was acquired by NEMS, Epstein’s company. He was considered an insider and a trustworthy member of the band’s managerial machine.

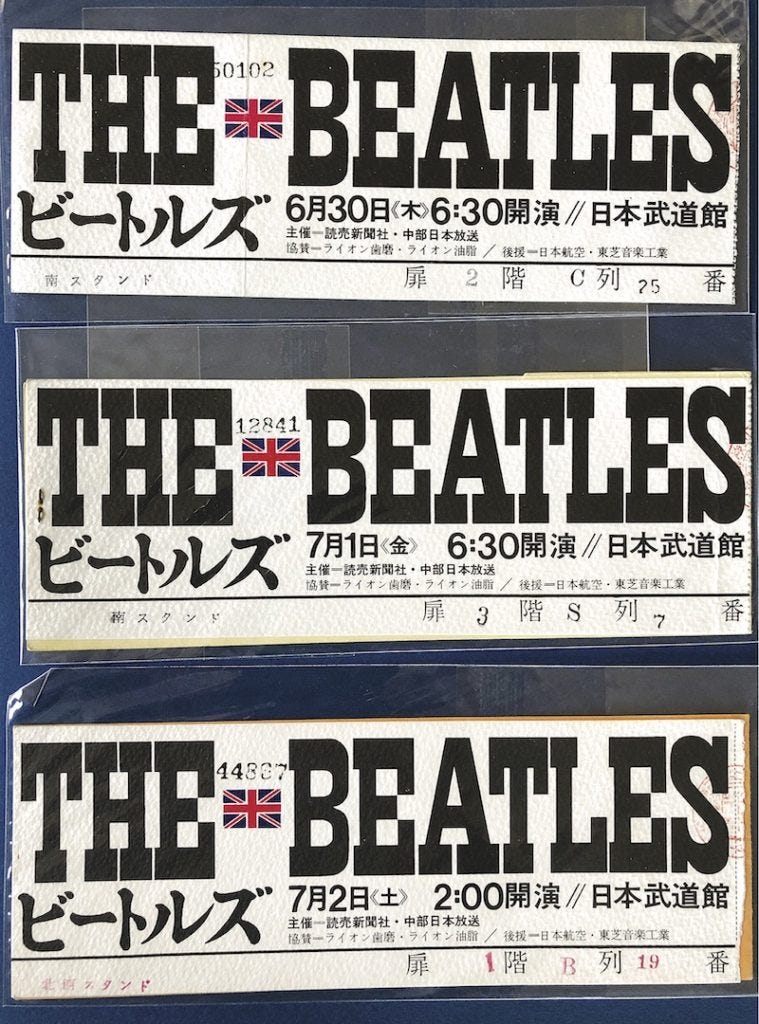

Nagashima Tatsuji, pictured with Brian Epstein and an unknown lad.

Nagashima was at that time the president of a booking company, Kyodo Kikaku Ejenshii [Agency] (now called Kyodo Tokyo). He had spent most of his childhood in New York and London, and it was in the English capital that he had attended the Woodstock – the same institute where Victor Lewis was studying.

When the time came for Lewis to establish contact with a Japanese promoter, he remembered Nagashima and his brother Hideo (they were, after all, the only Japanese boys in the school). Nagashima was the perfect man to help Lewis navigate the unknown Japanese market as he spoke English fluently, was familiar with English and American music, and by 1966 had being managing local jazz singers and bringing foreign artists to Japan for several years.

Lewis first contacted Nagashima on 18 March 1966. Here is how Nagashima remembered that conversation (as gathered by a Japanese publication devoted to the Beatles):

I got a phone call from Brian Epstein’s partner Vic Lewis, who said: “The Beatles want to come to Japan. Please help me make it possible. So it wasn’t us who called them, the phone call came from their side. Japanese enterprises at the time couldn’t just use foreign currency as they pleased, and we thought because it was the Beatles they surely would require a large payment. However, Vic said, “we won’t make you lose money on this.”

Even according to journalist Yukawa Reiko who worked with Nagashima on the tour, Lewis said that “no matter how low the fee is, the Beatles want to come to Japan.” As a matter of fact, Epstein was ready to accept any reasonable figure from the Japanese side, and most importantly he didn’t want the tickets to be too expensive because he didn’t want foreign promoters in the future to be put off by the Beatles’ unacceptable financial requests.

Vic Lewis said, “we won’t make you lose money on this [the Beatles tour in Japan]

On 22 March Nagashima flew to London and New York to discuss appearance fees, the venue, and ticket pricing with Epstein, and the contract was signed on 26 April. Though Nagashima thought that hardcore fans were prepared to pay as much as 10,000 yen for the premium tickets, they agreed to keep prices much lower: a bargain 2,100 yen for premium tickets which happened to be the same price of a record album. Cheaper tickets cost respectively 1,800 and 1,500 yen. As a matter of comparison, the average monthly salary of an office employee at the time was 33,100 yen.

However, in spite of the fact that Epstein was ready to meet the Japanese halfway and things looked good on the ticket pricing front, the numbers Nagashima was staring at were still formidable:

- 54 million yen for the Beatles (10,800,000 yen per show x 5 shows)

- 5.5 million in airfare for 11 people

- 3.6 million in hotel fees

To these, one should add 102,700,000 yen for the cost of using the concert venue (the Nippon Budokan) for five shows.

Nagashima began to hunt for companies who would sponsor the tour. In the end, he managed to gather a varied lineup:

- Yomiuri Shinbun (one of Japan’s leading daily newspapers)

- Chubu Nippon Hoso (Chubu Broadcasting Corporation, or CBC, a Nagoya-based broadcaster)

- Japan Airlines (JAL)

- Odeon Records (a music label that had the rights to distribute EMI records in Japan)

- Lion Toothpaste (a pharmaceutical company)

- Toshiba Ongaku Kogyo (a leading music company that later became EMI Music Japan before folding in 2013)

Among the above-listed companies, CBC played an important role because agreed to contribute a lot of the money Epstein wanted to be paid in advance. In exchange for their financial help, they were given the rights to show the concerts in the Chubu region (Nagoya and surroundings).

Ticket-selling was a nation-wide operation, with applications only accepted by mail, and was temporarily disrupted by a fraudulent scheme in Osaka that was discovered on 21 May and caused 600,000 yen in damages.

While the Yomiuri Shinbun, having an economic interest in the success of the event, was hyping the Beatles up, being careful to play down the supposed danger they posed to Japanese culture and society, their rivals immediately went to war with a frenzy of escalating headlines including:

Go hoomu Biitoruzu (Beatles, go home)

Kutabare Biitoruzu! (Drop dead, Beatles!)

Biitoruzu nanka koroshichae! (Kill the Beatles!)

Regular TV commentators called them “crappy” and declared that “monkey-dancing to electric guitars is an impediment to human progress.” They wondered why the country had to endure the use of the Budokan by “beggar artists” and concluded that because their music was trash, they should instead do their concerts at Yumenoshima, an artificial island in Tokyo Bay built using waste landfill that at the time was used as a dump (today it contains a park, a stadium, a barbecue area and a botanical garden. It was also chosen as the site of the archery event of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games).

Yumenoshima, the dump.

Aerial photo of Yumenoshima in 1989 (the first time I visited Japan).

The Yomiuri responded to these attacks by praising the band as “musical envoys of international good will, as decorated by their Queen.”

In the end, while part of conservative, mainstream Japan was certainly against the band and the influx of Western culture, the media must be blamed for creating a sentiment of fear about public morals and exaggerating the dangers John, Paul, George and Ringo posed to the sacred Land of the Gods. (To be continued)

Considering all the problems surrounding the Beatles’ trip to Japan, it’s almost a miracle that they finally managed to play in Tokyo. In the end, Nagashima Tatsuji played a pivotal role in making their first and last Japanese adventure a reality. I will devote my next chapter to Nagashima-san, so stay tuned!

Great insight into the mentality and social conventions of the era - here, in Australia, we weren't any better! Monkey dancing to pop music is exactly what an uptight society needs in order to let go.

Great backstory details & look forward to the 3rd installment! A few of my English students in Tokyo had attended one the concerts. Another one said, "I could hear the Beatles from my college dorm room in Suidobashi while I was studying. The sound was very big." When I then asked her if she had tried to get a ticket, she replied, "Oh no. I wasn't that type of girl." Her not going on to say that her thinking later changed, I was left to wonder if perhaps her mind still contained some of the poison that some media outlets -- or more likely her conservative & fearful parents -- had instilled.