A scandal that deposed one of Japan's most well-known celebrities and endangered one of its largest broadcasters has shaken the country's entertainment sector for months.

However, others think it has also signaled a shift in the way sexual assault cases are seen in Japan, where victims have often been shamed into silence.

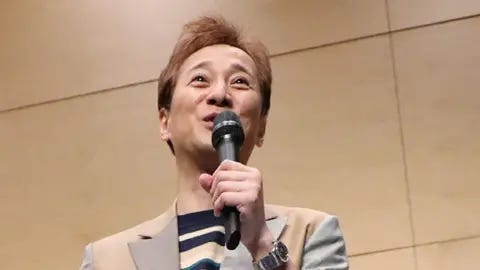

Nakai Masahiro, a well-known personality and top presenter for Fuji TV, one of the largest broadcasters in the nation, was at its center.

Nakai, a former member of the J-pop boy band SMAP, was charged in 2023 with sexually abusing a lady during a dinner party.

The revelations, which were first reported by Shukan Bunshun magazine after appearing in the weekly tabloid magazine Josei Seven last December, were the most recent in a string of celebrity scandals in Japan, including the late entertainment tycoon Johnny Kitagawa's abuse of hundreds of boys and young men over a 60-year period.

Nakai denied using force on the woman and would not acknowledge his culpability. In a statement, however, he expressed regret for "causing trouble" and claimed to have "resolved" the issue through a deal that was apparently worth over half a million dollars.

However, he was compelled to declare his retirement from the entertainment business in January as public outrage grew. Additionally, a show that Nakai frequently served as an MC on has been discontinued by TBS Television.

Fuji TV has been severely impacted.

The broadcaster's image has been destroyed. Some of its top executives have been forced to resign, and its revenue is in jeopardy.

As indignation increased, prominent corporations like Nissan and Toyota withdrew their advertisements from the broadcaster. Since learning of the accusations, Fuji TV has acknowledged that it permitted Nakai to continue hosting shows.

'Keep silent to keep your job'

Kojima Keiko, a TV personality with 15 years of experience in Japan's media sector, told the BBC that "if this had happened ten years ago, there would not have been this outcry."

One of the worst-kept secrets in Japan is the prevalence of sexual violence against women. According to a 2020 survey, almost 70% of sexual assaults in the nation go unreported. Furthermore, approximately 10 to 20 out of every 1,000 rapes in Japan result in a criminal conviction, and less than half of convicted rapists are imprisoned, per a 2024 study published in the International Journal of Asian Studies.

"There's still a prevalent attitude of shoganai or “there's nothing you can do” that is being projected on women - so they're encouraged to keep silent," Japan Women's University Professor Osawa told the BBC.

She went on to say that this culture of silence was influenced by the fact that women were rarely taken seriously and lacked the appropriate channels to even report such occurrences.

According to Ms. Kojima, many young women felt they had to remain silent in order to maintain their employment in the media sector, which in particular has a long history of impunity and lack of accountability.

Men frequently made offensive remarks about women's ages, bodies, or appearances. She recalled being asked how many people she and her coworkers had sex with.

"We were supposed to respond amusingly and without becoming upset or offended. Every day I witnessed sexual harassment and various sorts of mistreatment of women. To become a full-fledged TV or media professional, a woman had to adjust to these circumstances.

According to Kojima, women had to endure sexual harassment in order to maintain their employment.

The prevalence of dinners and drinking parties with young women and celebrities has also come under scrutiny in the Fuji TV case.

Shukan Bunshun later withdrew a report that said the alleged assault occurred at a party hosted by Fuji TV, but Ms. Kojima told the BBC that using women as "tools for entertaining" was typical.

"In Japanese working culture, it's an everyday practice to half-forcibly take young female employees to events to entertain clients," she stated.

"When young women join them, guys are pleased. There is a widespread belief that women are like presents and that inviting a young woman along is a sign of hospitality.”

Women's rights advocates have been inspired by the scandal's aftermath because of this.

Kitahara Minori, one of the founders of the Flower Demo movement, which organizes monthly gatherings of survivors of sexual violence and their allies in public places, said that she was taken aback by the sponsors' quick and harsh response.

"Even if it's more of self-preservation than human rights for sponsors, this is a turning point for the MeToo movement in Japan," she stated to the BBC.

"It's up to us how big we make it."

Deeper in disgrace

Almost fifty businesses have abandoned Fuji TV.

Additionally, the Japanese government has canceled all of its upcoming and current network ads. Additionally, it has urged the broadcaster to win back the confidence of advertisers and viewers. Fuji TV appears to have done neither thus far.

The controversy and Fuji TV's complicity in its concealment have sent the firm into a crisis management tizzy that appears to have resulted in further embarrassment and heightened public ire.

Minato Koichi, the president of Fuji TV, said that the business was aware of the accusation soon after the purported incident.

However, he claimed that they "prioritized the woman's physical and mental recovery and the protection of her privacy" when they decided not to reveal it at the time.

In 2023, Nakai Masahiro was charged with sexually abusing a lady during a party.

The business conducted a second, ten-hour press conference after the first one, which was intended to calm the fury, turned into a PR catastrophe.

It was meant to convey regret.

Both Fuji TV President Minato and Chairman Kano Shuji announced their resignations with a humble bow. The company said that Shimizu Kenji, its executive vice-president, will take Mr. Minato's place as president.

However, given that the president's successor was a member of the same leadership group, this was perceived as more of a face-saving move to please advertisers than a significant shift.

However, prominent cases like Fuji TV set significant precedents for actual change, Professor Osawa told the BBC.

And this is the most recent chapter in a string of high-profile instances involving sexual misbehavior that have sparked discussions about women's rights in Japan.

Among these is the example of journalist Ito Shiori, who in 2017 came to represent the nation's MeToo movement. She made the uncommon move of coming out with claims that she had been raped by famed TV journalist Yamaguchi Noriyuki after they had met for drinks. In 2019, she prevailed in a legal case against him, notwithstanding his denial of the accusations.

"People have now begun to realize that it was acceptable to voice their concerns about this [sexual harassment]." "We are altering what we consider to be the standard," Ms. Kojima stated.

However, according to Ms. Kitahara and Ms. Kojima, Japan is not progressing quickly enough.

"That generation [of media leadership] needs to step down, in my opinion. A new corporate culture must be developed by the industry. According to Ms. Kojima, the transformation is gradual.

"The problem of violence and exploitation has long been disregarded by the TV business, which has also failed to adequately assist the victims. The same thing will occur again if the underlying cause of the issue is not addressed.

According to Kitahara, she hopes to never again attend a flower demo.

Professor Osawa concurs that the pervasive power disparity in Japan means that the nation still has a long way to go.

A patriarchal society still views males as the "breadwinners" and women as the "caretakers" despite the fact that women have been employed for decades, she continues.

"This is a crucial moment... However, it's uncertain how much attitudes will shift," she stated.

Ms. Kitahara claims to be both hopeful and incensed, saying, "The sexual violence never stops."

"Every month during Flower Demo [protests], I still run into new survivors and find out what happened to them. The other day, we had a female from high school. She was most likely in junior high when we launched the initiative [in 2019], she said.

"I hope for the day when I will never have to go to a Flower Demo protest again."

such is the dansonjyohi shakai. thats why my daughter cant be here past 12 years old. 7 years and one month to go.

A first step in the right direction. I'm with Ms. Kitahara.